The Insurance Industry's Innovation Challenge

White Paper by The Institutes

Abstract: There is a tendency to view insurtech as the sole solution to the industry’s perceived innovation gap. This white paper from The Institutes suggests that being truly innovative means much more than simply embracing the promises of insurtech. What does it mean to be truly innovative, and what stands in the way of innovation? These and other questions are discussed, and a simple tool is offered to help companies assess innovation in their organizations and among their competitors.

Reviewing Forbes’ 2018 list of the 100 most innovative companies in the world, readers will see that no insurance companies are included on the list.[1] While this may be disappointing news, it should not be surprising. The insurance industry is too often absent from discussions of strategic innovation and its importance in paving the way for future success. And this isn’t just how experts in business management and strategy see the industry; consumers also tend to see the industry this way. Every year, Fordham University’s Gabelli School of Business and Rockbridge Associates update the American Innovation Index, which reflects consumers’ opinions on innovation from the businesses with which they engage.[2] Twenty-one industry sectors are examined, including “Auto, Property, Casualty Insurance Providers.” While there are standouts within the insurance sector, the sector as a whole ranked ninth from the bottom.

If business experts and consumers do not consider the insurance industry to be particularly innovative, then how do insurers see themselves? In a 2019 presentation at the Global Insurance Forum, The Institutes President and CEO Pete Miller reviewed the results of a recent survey of International Insurance Society (IIS) members in which senior-level executives identified and ranked various challenges and concerns facing their companies. Among all the issues considered, innovation was ranked the second-greatest concern. Only cybersecurity was considered more important than innovation.[3] Apparently, insurers largely agree with the assessments of their customers and business experts.

Why is innovation important? And is the industry’s so-called innovation gap really as wide as many seem to believe? Why is innovation such a challenge for the insurance industry? These questions are discussed in this white paper, along with experts’ suggestions on what needs to happen for the insurance industry to become more strategically innovative. A potential tool for assessing and comparing the innovativeness of different insurers is also suggested and discussed.

Why Is Innovation Important?

The importance of innovation is succinctly captured in the often heard warning to innovate or die, usually attributed to management expert Peter Drucker.[4] Simply seeking to avoid death, while obvious and universal, fails to instruct insurers on the particular consequences of not being innovative enough. Prominent examples from outside the insurance industry of failing to innovate—Borders, Kodak, Blockbuster, Sears—clearly illustrate its quick and direct consequences. For an insurance company, failure to innovate can be harder to detect and easier to conceal. What’s more, death by failure to innovate may be less recognizable due to regulatory oversight, an active merger and acquisition market, and an unusual level of brand loyalty on the part of many insurance consumers. (Multiple surveys from the Insurance Research Council indicate a reluctance by a large percentage of auto insurance consumers to shop for auto insurance.[5])

An insurer’s failure to innovate is more likely to appear as a relatively slow process—evidenced, at best, by a steady loss of market share, declining profits, and eventual acquisition by a stronger competitor or, at worst, by regulatory intervention followed by a combination of runoffs and book purchases by competitors. Notwithstanding the somewhat unique experience that may follow for an insurer that fails to innovate, that failure is ultimately just as fatal to an insurer as it is to any other type company.

How Large and Pervasive Is the Industry’s Innovation Gap?

This rather harsh assessment of property-casualty industry innovation is not universally shared. The authors of a 2013 report proposed that “the conservative reputation the industry enjoys has served to camouflage a tremendous track record of innovation,” citing as evidence a range of past innovations including fire brigades in colonial America, mortality tables, and the embrace of big data.[6]

Insurtech is widely viewed as a positive development for the industry and an example of successful innovation.[7] It may be inaccurate, however, to interpret its proliferation as a sign of the industry’s turn toward innovation as a way of business. Much of the insurtech activity to date has originated outside the industry as external technology firms have either entered the insurance business directly as disrupters or have formed business-to-business relationships with incumbent companies looking to tap into the benefits of digital technology.

Expectations are high that the investment in insurtech will yield lower costs and higher margins. Some, however, have started to question the value proposition of insurtech. As one industry analyst recently wrote, “Unquestionably a good number of insurtechs are genuinely adding value…but if we look more broadly at what has gone into this space (time, resources, cash) and assess what has come out, there is a very large sinkhole somewhere.”[8] That insurtech has not pulled the insurance industry out of the innovation doldrums is not a criticism of insurtech as much as it is a reminder of what it really means to embrace innovation as a way of doing business.

What Does It Mean to Be Innovative?

The perception that the insurance industry is not innovative enough suggests implicit assumptions about what innovation means and how innovative the industry should be. The dictionary definition of innovation (“a new idea, method, or device; the introduction of something new”[9]) isn’t particularly helpful in understanding the meaning of innovation in the context of the modern business enterprise. Leading management experts would argue that the creation or introduction of “a new idea, method, or device” does not constitute innovation unless it also enhances value to customers and the firm. Sawhney, Colcott, and Arroniz, at the MIT Sloan School of Management, thus define business innovation as “the creation of substantial new value for customers and the firm by creatively changing one or more dimensions of the business system.”[10]

From this definition, Sawhney, et al., identify three key defining characterizations of innovation:

- Innovation is about creating new customer value, not new things. The customers of the insurance organization signal the value of innovation by paying for it.

- Any dimension of a business system can be involved. Innovation is not just about insurtech or even technology generally.

- Innovation must be systemic across the business enterprise to be successful. Managers must understand how any innovation affects, and is affected by, other areas of the enterprise in order to fully realize potential value.[11]

What motivates innovation? The origins of innovation, according to Drucker, are rarely an unexpected “flash of genius.” Instead, most successful innovation is a result of “a conscious, purposeful search for innovation opportunities.” Drucker identifies several situations that frequently provide opportunities for innovation:[12]

- Unexpected occurrences. When something unexpected happens, it often means that one’s assumptions about the occurrence were incorrect. Identifying and understanding why what happened was unexpected can often reveal previously unseen opportunities.

- Incongruities. An incongruity means that something isn’t right or is out of place. Finding out why may reveal opportunities for innovation.

- Process needs. Most businesses are defined in large part by multiple processes and procedures. Opportunities for innovation can be revealed by examining those processes and procedures with improving effectiveness and efficiency in mind.

- Industry and market changes. How a company views itself relative to its industry and market is usually based on stagnant models and beliefs. An industry or market that is changing is a signal that opportunities for innovation may be present.

- Demographic changes. Failure to acknowledge and understand the implications of changing demographics, such as an aging population, can be devastating. Conversely, superior knowledge of changing demographics can provide opportunities for innovation.

- Changes in perception. Consumers’ views of new products or services can change for reasons known and unknown. A sudden shift from perceiving something to be undesirable to believing it is essential can present opportunities for innovation. Be on the alert for changes in perception.

- New knowledge. Scientific breakthroughs often lead to innovation opportunities. New knowledge in other areas, such as consumer preferences, can also present innovation opportunities.

What Gets in the Way of Innovation?

The absence of any of the key elements of innovation described above can doom efforts to become an innovative organization. Three additional obstacles can also undermine efforts to innovate:

- Lack of a change-oriented culture. Embracing change is essential to becoming an innovative organization. Without change, innovation is impossible, and the most important change that has to occur is to move from a tradition-bound way of doing business to one that not only embraces change but actively seeks opportunities to change.

- Putting innovation in a silo. Some companies have actually created chief innovation officers and innovation departments. Is that really a good idea? Perhaps it is if the individuals involved truly understand that successful innovation permeates every corner of an organization and are empowered to act across internal boundaries. The danger, however, is that innovation becomes just another functional silo with little chance of spurring real change.

- Suffocating regulations. Much has been written about how product and price regulation in the industry stifles innovation.[13] The insurance industry, to a large degree, is structured around regulatory requirements and demands that often discourage, if not preclude, creative change.

A Simple Tool to Begin

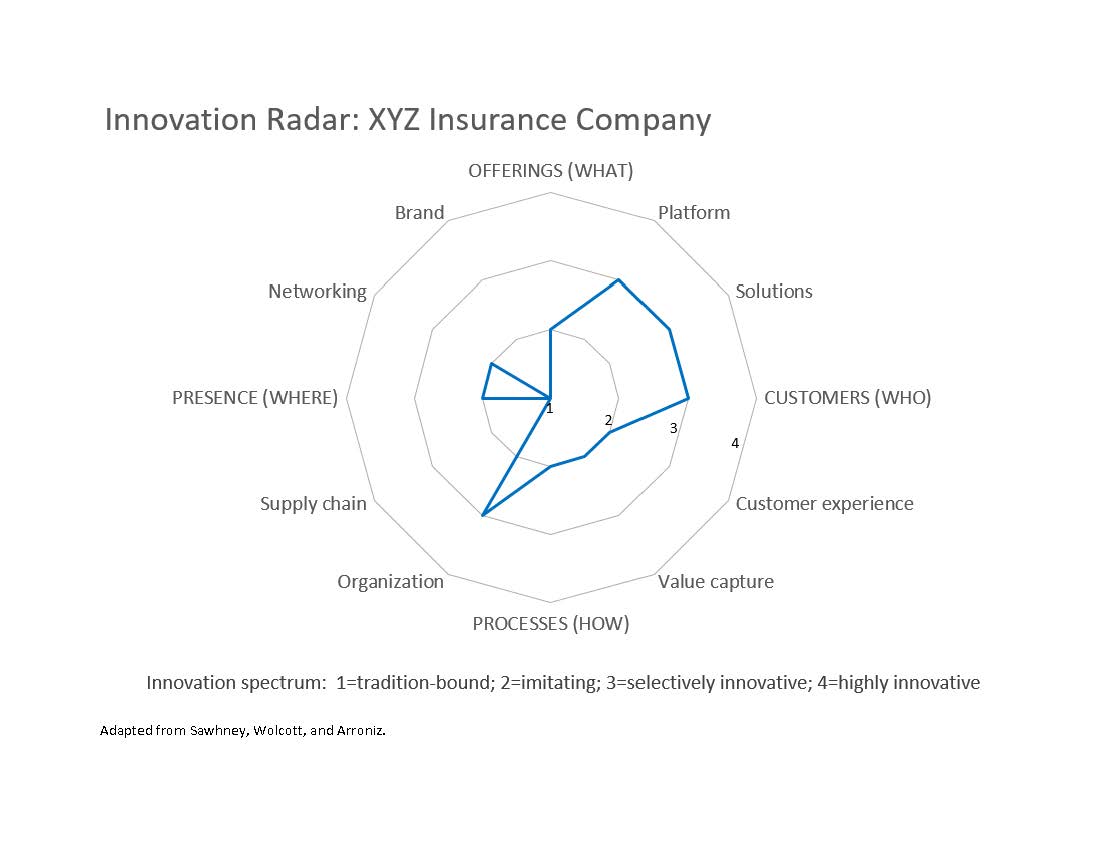

Where does an insurer begin if it wants to become more innovative? A good place to start would be to conduct a system-wide assessment of the company’s current state of innovation using the “innovation radar” developed by Sawhney, et al.[14] The innovation radar examines 12 primary dimensions “through which a firm can look for opportunities to innovate” and invites an assessment of how innovative a company is with respect to each dimension. The tool is consistent with Drucker’s view that an innovative company is engaged in “a conscious, purposeful search for innovation opportunities.”[15]

The innovation radar is not a means for measuring innovation outcomes or company performance. It is a tool for assessing the degree to which a company has embraced innovation as a continuous and fundamental way of doing business. The innovation radar was not designed specifically for the insurance industry, but there is no reason why it cannot or should not be used by insurance organizations. If the dimensions described here seem inapplicable or if other important dimensions are missing, the innovation radar can easily be adapted to be more relevant and useful. For discussion purposes, the tool has been modified to include an innovation spectrum, a four-point scale for measuring current innovation efforts, ranging from tradition-bound to highly innovative. The tool can easily be adapted to incorporate other measures or scales for scoring levels of innovation along each dimension. The innovation dimensions are discussed below using the hypothetical XYZ Insurance Company as an example.

Among the 12 dimensions of innovation are four described by Sawhney, et al., as business anchors, which are common to virtually all businesses:

- Offerings. What products and services does the company offer and how are they valued by customers? Are there opportunities to provide products and services addressing currently unmet needs and that customers will value? XYZ offers basically the same insurance products across the board as most other insurers.

- Customers. Who does the company view as its customers? Is it limited to the named insured only? This insurer has expanded its perspective on who its customers are to include entire households and even communities. This expanded perspective has revealed several opportunities to better serve the company’s customers.

- Processes. How does the company configure internal business activities to enhance effectiveness and efficiency? XYZ is making an effort to compare its internal processes with those of other companies, but primarily to ensure that its processes are consistent with common industry practices.

- Presence. How does the company interface with customers? Where do customers go in order to purchase the company’s products? XYZ is looking carefully at how competitors have embraced social media as a business tool and is designing a model to imitate the practices of these other companies.

Eight additional innovation dimensions are included around the four anchors:

- Platform. Does the company utilize a platform with common elements to which different components can be added to expand the range of products and services it offers? XYZ is actively engaged in few pilot tests of a modular approach to policy production. The expectation is that it will result in fundamental changes in how its products and services are configured.

- Solutions. Does the company seek to help customers address important risk concerns effectively and efficiently, or does it simply seek to entice potential customers to purchase existing products? XYZ has deployed an online tool designed to identify customer needs from a broad risk management perspective.

- Customer experience. Can the company examine interactions with customers from the customer’s perspective? What does a customer value in the manner in which she interacts with the company? XYZ has attempted to better understand customer experience through surveys, focus groups, and online feedback from its website. These are common industry practices.

- Value capture. This is about how a company recaptures the value it creates and provides to customers. Are all potential revenue streams being tapped? XYZ has enhanced and broadened the means by which payments are received from customers, but it has attempted little else in this area.

- Organization. How does the company organize its resources to perform the tasks necessary to do business? Are resources being siloed, creating barriers to effective collaboration and maximum return? XYZ has pulled down barriers to collaboration and is exploring new and novel ways to spark innovation in how resources are deployed to create maximum value.

- Supply chain. For an insurance company, this dimension involves the sequencing of information from initial source to final use. XYZ is laboring under a number of legacy systems that are unable to work together to maximize information flow and use information to greatest advantage throughout the company.

- Networking. How well are customers and companies connected to each other? Active networks can enable insurers to remain aware of customers’ changing needs more quickly. XYZ is looking closely at what others are doing to connect better with their customers. It is just getting started.

- Brand. Does the company’s brand remind and reinforce the value customers attribute to the company’s products and services? Is the brand being effectively used? XYZ has yet to consider how its current brand is viewed by customers and the general public. With some of the initiatives now underway to enhance the customer experience, XYZ is considering options.[16]

XYZ Insurance Company’s scoring along each dimension included in the innovation radar provides an intuitive assessment of innovation company-wide. A highly innovative approach on some dimensions, but little innovation on other dimensions, indicates that the company is not systemically innovative and points to areas where the company can focus on uncovering more opportunities to innovate in the future. The innovation radar tool can also be useful for exploring how innovation in one company compares with innovation in other companies. With sufficient competitive intelligence, one can prepare an innovation radar assessment for competitors and use that information to prioritize future opportunities.

Conclusion

Innovation in the insurance industry is inevitable, either as incumbent insurance organizations embrace the meaning and value of being truly innovative, or as external disrupters enter the market with an innovation mindset already in place. In either case, those organizations that reflexively resist the change that innovation requires or hobble the innovation process with bureaucratic requirements and immutable functional boundaries will inevitably be pushed aside as more innovative competitors and new entrants thrive in a new marketplace that rewards innovation. A wildcard in this evolutionary process is the insurance regulatory system and environment, which must fully enable and support innovation while minimizing the risk to insurance consumers.

The insurance industry is in the midst of fundamental change. The growth of insurtech suggests a strong willingness to move forward, but it is unclear whether insurtech is the only way in which incumbent insurance organizations intend to embrace innovation or whether a more systemic transformation is underway, where innovation becomes a mindset that permeates the entire organization. Time will tell.

[1]Forbes, “The World’s Most Innovative Companies,” www.forbes.com/innovative-companies/list/#tab:rank (accessed February 18, 2020).

[2]American Innovation Index, “Market Summary Report,” americaninnovationindex.com/ (accessed February 18, 2020).

[3]“Turning Insight into Opportunity, International Insurance Society Global Concerns Survey,” Global Insurance Forum, April 2019.

[4]Adi Ignatius, “Innovation on the Fly,” Harvard Business Review, hbr.org/2014/12/innovation-on-the-fly (accessed February 18, 2020).

[5]Insurance Research Council, Shopping for Auto Insurance and the Use of Internet-Based Technology, (Malvern, Pa., Insurance Research Council, 2015), p. 16.

[6]Howard Mills and Bernard Tubiana, “Innovation in Insurance, The Path to Progress,” Deloitte Insights, www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/topics/innovation/innovation-in-insurance.html (accessed February 18, 2020).

[7]Insurtech describes “technology-led companies that enter the insurance sector, taking advantage of new technologies to provide coverage to a more digitally savvy customer base,” from “Insurtech—The Threat That Inspires,” McKinsey & Company, March 2017, www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/insurtech-the-threat-that-inspires (accessed February 18, 2020).

[8]Andrew Johnson, “Quarterly InsurTech Briefing, Q3 2019,” Willis Towers Watson, www.willistowerswatson.com/en-US/Insights/2019/10/quarterly-insurtech-briefing-q3-2019 (accessed February 18, 2020).

[9]"Innovation," Merriam Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/innovation (accessed February 18, 2020).

[10]Mohanbir Sawhney, Robert C. Wolcott, and Inigo Arroniz, “The 12 Different Ways for Companies to Innovate,” MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2006, p. 76.

[11]Sawhney, Wolcott, and Arroniz, p. 77.

[12]Peter Drucker, “The Discipline of Innovation,” Harvard Business Review, August 2002, hbr.org/2002/08/the-discipline-of-innovation (accessed February 18, 2020).

[13]Leading in Times of Change, Insurance Regulatory Outlook 2019, Deloitte Center for Regulatory Strategy, Americas, December 2018, www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/regulatory/us-insurance-regulatory-outlook-2019.pdf (accessed February 18, 2020); Sharon Tennyson, The Long-Term Effects of Rate Regulatory Reforms in Automobile Insurance Markets, Insurance Research Council, (Malvern, Pa., Insurance Research Council, 2012).

[14]Sawhney, Wolcott, and Arroniz.

[15]Drucker.

[16]Sawhney, Wolcott, and Arroniz.