Long-Term Care Reform in Canada: If Not Now, When?

Derek J. Houle, Head of Canadian Legacy and Inforce Management, Manulife

Section 1: The Current State

Long-term care (LTC) “encompasses a range of health and personal care services provided to individuals, primarily seniors, with complex support needs living in designated LTC homes.” [4] It includes LTC homes but also covers other services and care options provided in the community and at home.

While LTC insurance products exist in Canada, the needs are unclear as there is an incorrect perception or assumption that the universal health care system covers LTC [5]. The insurance industry is uniquely positioned to educate individuals and collaborate with the public sector to address the needs of aging Canadians. Only by public and private organizations working together can we address the current challenges and those ahead.

1.1 Long-Term Care in Canada

While Canada has universal health care, the system is complex to navigate for the average person, especially as one gets older and needs increased care [5][26]. Publicly subsidized LTC is one of the only options for the sick and elderly at the provincial level; but the lack of beds and staffing leads to long wait times and limited beds for those in need [10][20].

Legislation related to LTC is established at the provincial level, leading to a lack of consistency across the country [26]. The lack of portability and inconsistent care that varies by location is evident, even within provinces. While this report will investigate LTC at the national level, some of the research will focus on the province of Ontario, where 45.7 percent of home care providers are located [26].

Provincial funding is based on general tax revenues on a “pay as you go” basis, with no “pre-funding” for older age care where the bulk of healthcare spending occurs [10].

The LTC insurance industry in Canada is virtually non-existent due to government controlled entry into LTC facilities, unclear out-of-pocket expense requirements, and the perception that universal healthcare means LTC.

With Canada’s elderly population growing, similar to other industrialized nations, the stress on the system and caregivers will continue to increase until changes are made to the current Canadian system. At this time, the bulk of government funding to LTC goes to publicly funded LTC homes and very little is used on home care [10].

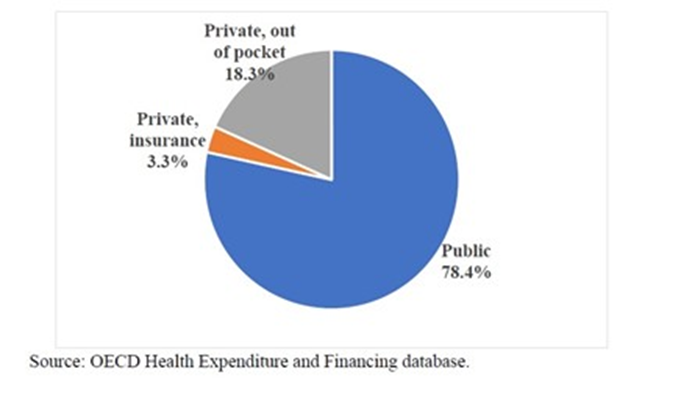

Figure 1: Long-Term Care Financing by Source

Source: Milligan, p.40

1.2 Canadian Legislation

In Canada, the Canada Health Act (CHA) of 1985 is the legislation that sets out the main objective of healthcare policy in Canada. It states that its purpose is “to protect, promote and restore the physical and mental well-being of residents of Canada and to facilitate reasonable access to health services without financial or other barriers.” [14]

The Act delegates healthcare to the provinces, and LTC is not one of the health services covered. However, care in nursing homes and home care are mentioned in the CHA as “extended care services,” and they are not “insured” health services [29].

As a result, LTC is at the discretion of the provinces and territories. While each province does provide LTC benefits as part of its system, the definitions are not consistent, the amount of government subsidy varies, home care versus facility care is inconsistent, and the whole system is confusing and unclear for everyone [28].

In 2017, the Canadian Health Accord was introduced to transfer $6 billion over 10 years to improve access to home and community care services. While this was an attempt to improve a fragmented situation, there has been no sign of improvement related to wait times despite this increased funding [28].

1.3 Funding

In 2018, nursing home care accounted for $27 billion total costs, with $20 billion (74 percent) from public funds and $7 billion (26 percent) from private funds [29].

In 2017, approximately 17 percent of the population was age 65 or older. That same cohort accounted for 47 percent of total healthcare expenditures, either out-of-pocket or subsidized. As the population of those aged 65+ grows, the balance of healthcare spending will tilt above the 47 percent, leading to increased funding requirements from individuals—either in the form of out-of-pocket expenses or increased tax revenue.

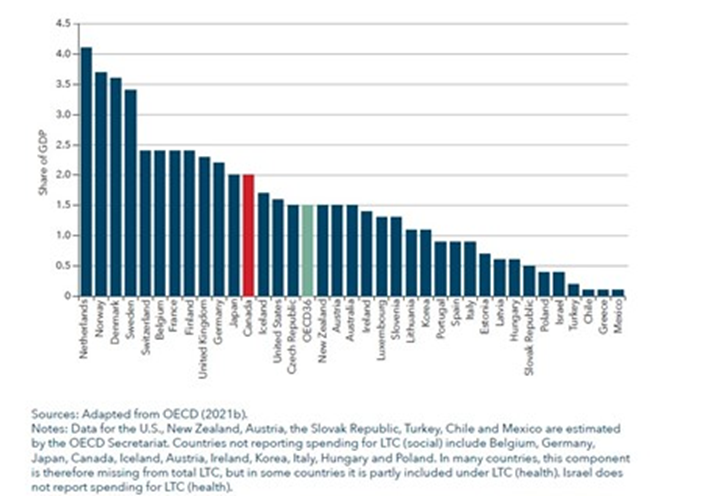

Canada spends roughly 2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) on LTC and 9 percent of GDP on other healthcare services. Since the CHA is primarily a financial bill, there is a large amount of money available to the provinces, but all of it comes with federal strings. This centralized control of regional use of money is not effective and stifles any innovation at the provincial and community level.

Figure 2: Long-Term Care Spending as a share of GDP, 2019

Source: Woolley, p.34

1.4 Regulation

All LTC facilities are regulated by their respective governments, setting the standards and auditing the facilities. Almost 70 percent of the facilities in Canada are publicly owned (46 percent) or private not-for-profit (23 percent) [9]. Admissions are also controlled by governments which determine who is eligible for care [28].

The government controls what homes are eligible, how they are run, and who can go into them. This system leads to lack of choice, lack of competition, and barriers to entry.

1.5 Home Care versus Facility Care

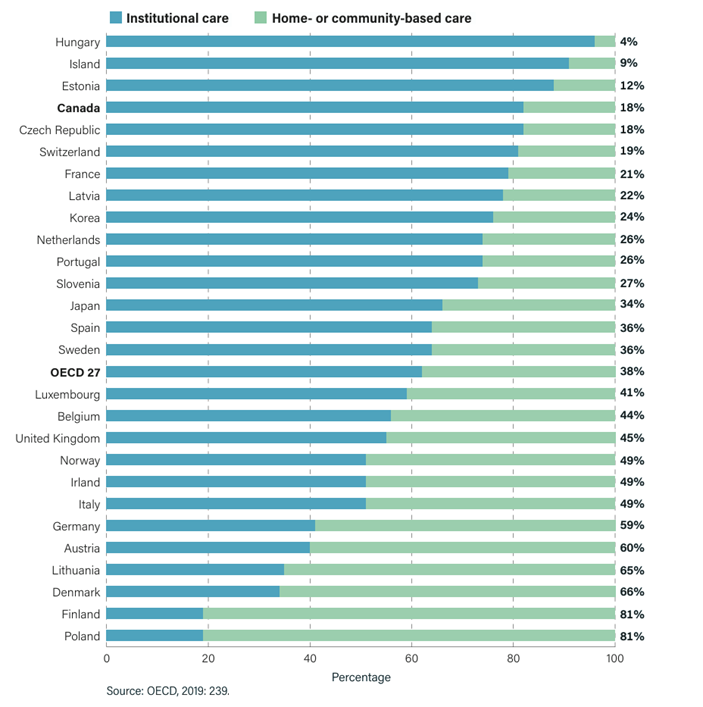

Many older individuals value their independence, and moving to a facility is not what they want. Home care is the preferred approach by seniors and, in theory, should reduce the stress on the universal healthcare system [13].

However, Canada has not embraced home care as much as other developing nations have, with only 18 percent of care provided in the home versus facility for Canada. Germany, for example, has 59 percent of the care provided in the home or community, while Japan has 39 percent (see table below). Given the long waiting lists for facilities, this translates to a significant amount of the elderly population remaining in their homes with unmet care needs.

Figure 3: Institutional Care vs. Home and Community Care Care

Source: Labrie, p.9

1.6 Private Insurance Market

Private LTC insurance in Canada is almost non-existent [32]. Some insurance carriers have had success selling LTC as more of a disability insurance coverage for younger ages, but the private LTC market is not very robust [32].

Given the challenges with the system, private insurance would not provide anything beyond what prudent retirement planning already provides (i.e., cost of rent, laundry, and housekeeping). In addition, there is a perception or assumption that the government will take care of the elderly. If there were a private LTC option for individuals, this would necessitate the need for insurance; but given the current system, it does not make sense to buy the types of products available today.

Section 2: Stress on the Current System

2.1 What is the Trend?

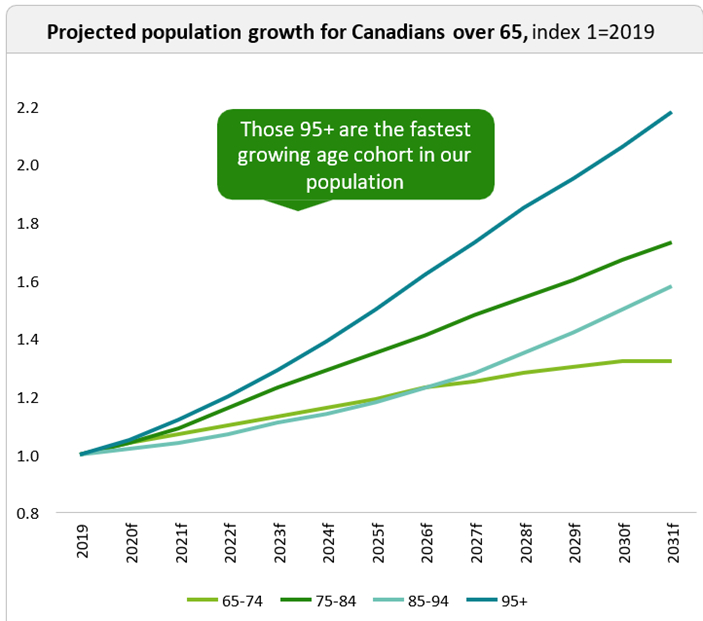

There is an overall trend in industrialized nations of rapidly aging populations. In Canada, the large population of baby boomers began turning 75 in 2021. This age and beyond is when a greater need for higher care and support starts to grow [6]. By 2036, Canadians over age 65 will comprise 25 percent of the population and over 1 million will be diagnosed with dementia [5]. The number of people aged 80+ will triple between 2018 and 2034 [28].

When this aging population is combined with a sustained increase in lifespans [11], and a large increase in chronic diseases [28], it is clear that “Canada is not prepared to face the challenges associated with these … changes and the growing needs that will be associated with them.” [28]

These higher-care needs are coupled with the desire of seniors to age at home, but the infrastructure is not in place to support their preferences [17]. The increase in percentage of older Canadians who are single and the decrease in unpaid private care (family members) is leading to a social and political crisis.

Figure 4: Population Growth

Source: CMA, p.5

2.2 Aging at Home

In 2019, a survey showed that the majority of Canadians aged 65+ plan to remain at home during their senior years [6]. While most seniors prefer home care, there is a long wait for this service, like institutions [28]. There is also a lack of sufficient caregivers in this field [6]. Many Canadians believe that LTC will be paid for by the universal health care system; however, at this time, LTC is not explicitly included in the CHA.

In 2024, most home care is “short-term, task-based and reactive” [13] and is not designed to support a wide range of physical, mental, and social health needs. Due to the lack of depth and availability when it comes to home healthcare, many seniors end up in emergency rooms, which places pressure on other areas of the healthcare system [18]. As a result, hospitals are in crisis due to overcrowding and the “alternative level of care” patients, which has contributed to the unplanned closures of emergency rooms [25].

Another crippling side effect of this lack of integrated home care is the pressure on informal caregivers, who are estimated to provide care to approximately 3 million Canadians [6].

Private organizations step in to handle home care needs that are not satisfied by the public system or families, and this is an out-of-pocket expense for seniors [28].

2.3 Stress is Everywhere

Seniors show a clear preference to age at home and receive care from family members. This preference has financial, social, and emotional consequences for all Canadians, not just the seniors and their families.

2.3.1 Informal Caregivers

If public agencies had to pay for what informal caregivers are currently providing for free, by 2050, the costs to the public sector will be approximately $27 billion [30]. By 2035, informal caregiving will account for 500 million hours annually. The increased need due to the aging population is combined with an overall reduced availability of family caregivers in the future [28]. The changing role of women in the workforce and lower fertility rates have resulted in fewer people able to fill the traditional role of the informal caregiver [34].

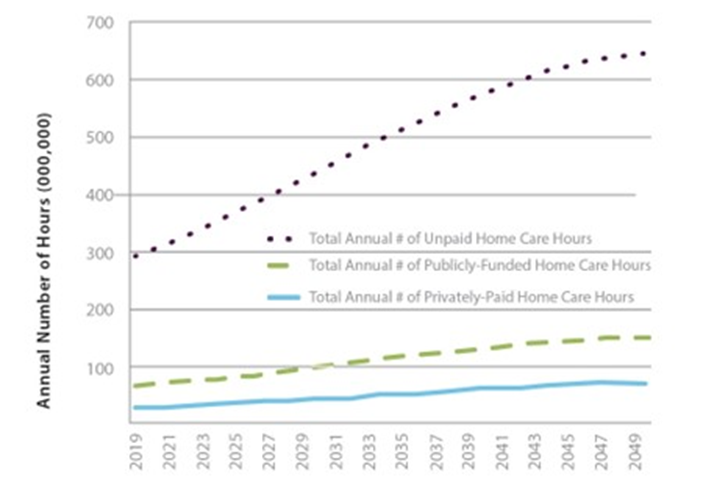

Figure 5: Annual Home Care Hours by type

Source: MacDonald, p.24

Unpaid informal caregiving labour would need to increase between 2023 and 2050 by 40 percent to keep up with growing care needs [11]. This concern for informal caregiving created the crisis in Japan that triggered the country’s move toward a social insurance scheme for LTC. With this reduction in informal caregivers, there is a higher risk of poverty and a 20 percent increase in mental health problems for these caregivers [22].

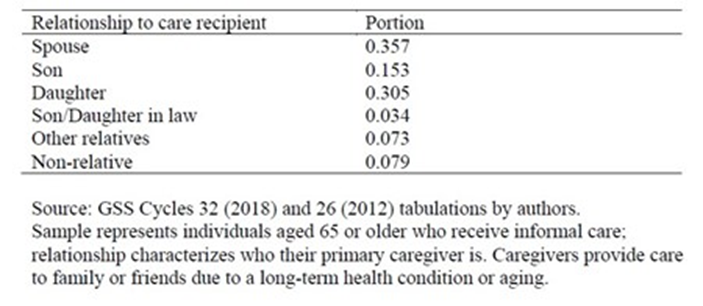

Figure 6: Primary Caregiver Relatiionship to Elderly Recipients

Source: Milligan, p.36

2.3.2 Formal Caregivers

Currently the care for seniors is a patchwork of services offered by family members, public health workers, and private health workers as well as hospitals. If a senior is moved from the emergency room into a hospital room, they will eventually be released or moved into an alternative level of care (ALC), which means they are waiting to be moved to LTC [6]. Until this happens, the hospital resources are unavailable to other patients while the ALC patients wait to be moved to a more appropriate setting. By making home care more readily available, the health system could free up staff time and other medical resources which are more expensive in hospitals and would also improve patient care for everyone [6].

If the current system of public home care continues, the province of Ontario will need to add 6,800 additional personal support workers to maintain the current level of service [17]. However, the current system is already not providing satisfactory care and is leaning heavily on informal and private caregivers; so only adding new personnel will not solve the underlying problems.

“Even now, with the full force of population aging yet to be felt, the system isn’t working well. There are long waiting lists to access long-term care facilities across the country. The quality of care provided leaves much to be desired, as was made painfully clear during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Publicly funded home care is difficult to access, but privately purchased home care is costly. Instead, the system relies to a great degree on spouses, adult children, and other caregivers, who report providing long hours of unpaid care, and feeling tired and overwhelmed.” [32]

Section 3: International Learnings

3.1 Germany

In 1995, there were many similarities between the German LTC system and the one in Canada. Like Canada, the German legislation largely excluded cognitive impairment and used a means-based assessment system for seniors requiring care [35]. Families were under stress to provide informal care and the system was state/province administered [35].

After years of discussion [33], the new program, with responsibility delegated to both private and public entities, was implemented quickly within five years and was widely supported by citizens and politicians [7]. The new system was based on universal eligibility and mandatory participation.

The financial sustainability of the program was one of the major goals of the new LTC system and was achieved using self-funding “sickness funds” that were funded by premiums [7]. These premiums were paid equally by employers and employees and amounted to 1.7 percent of salary [35]. There were also subsidies provided for the purchase of private insurance.

Citizens were allowed to receive care-in-kind or cash payments for half the value of the care to use as they wished [12]. This could be used to alleviate some of the stress of informal caregivers. The program was prefunded by money provided by the premiums and the sustainability was further enforced by front-loading LTC insurance contracts [2]. The success of the program hinged on the ability to “accurately forecast demand and associated expenditures.” [35]

The new focus on home and community care encouraged competition which strengthened the provider infrastructure, creating more choice for citizens and a form of quality control of the providers [13]. Approximately 250,000 new jobs were created as part of this provider network [35]. This focus on prioritizing home care matched the preferences of older adults and also helped with caregiver support.

The decentralized approach used in Germany increased flexibility and adaptability and improved the quantity and quality of home care [28]. There are now approximately 48 competing insurers providing care to all Germans, regardless of location, savings, or need [2].

The focus on informal caregivers, defined roles at the national and state level, and the financial sustainability of the dedicated LTC fund have made Germany the basis for many social insurance programs that followed.

3.2 Japan

Like Germany, Japan is also widely considered a success in terms of its LTC system. The desire for change was triggered by similar issues of an aging population, struggling caregivers, and the growing burden on public health care systems [28].

The crisis that pushed Japan to implement an LTC insurance program was its aging population, combined with increasing life expectancy plus an over-usage of hospital resources by the senior community.

Building on the German system, Japan focused on competition and choice instead of bureaucracy [40]. It decentralized responsibility for healthcare to local authorities and introduced premiums for people aged 40+ and co-payments for all citizens [28]. Japan also implemented a uniform price structure across the country with an emphasis on home care.

In Japan, care institutions are small in scale and built to satisfy user needs [42]. Citizens have a choice of providers and choose the type of care they wish to receive, with quality control managed by consumer choice combined with audits and evaluations that are published online.

Japan has used the new LTC environment to research innovative new solutions. They have invested in public agencies developing and funding nurse training programs and are investigating how to integrate foreign-born workers. Lastly, they are at the forefront of research into care technologies and the role of robots in healthcare [28].

3.3 Lessons Learned, Public Opinion, and Political Collaboration

The examples of Germany and Japan show how countries struggling with the same issues as Canada can provide innovative solutions that are supported by the majority. It is not enough to just increase transfers to a system that needs to be rebuilt.

In both countries, it took a crisis for their governments to make LTC a priority. Japan used Germany’s example—both good and bad—to use as a base for its social insurance program.

When research moves beyond these two countries, one can see that new countries that implement LTC strategies base their programs on the successes and failures of the ones that came before. For example, in both the Republic of Korea and Taiwan, there has been more of an emphasis on starting early and starting small.

The other important thing when using international examples is that the local culture and society will always play a role. In Germany, the pursuit of a cultural “social solidarity” fueled the overall acceptance by German society. In Japan, politicians had to acknowledge the entitlement Japanese citizens felt toward their healthcare or it could derail the entire program.

“…local politics and history will nearly always trump careful planning. History also affects what citizens feel is owed them, which in turn influences how a program evolves.” [34]

The desire for change is challenging when deciding to tweak “what is” or aim for “something better.” Even if policymakers create a completely new social insurance program, they must integrate this into existing programs. In some cases, like the Canada Pension Plan (CPP), the new program could use the public’s understanding of this system to aid their understanding of a new system; however, the LTC insurance system needs to be a politically decentralized program supported by cost-sharing that is a collaboration between public and private sectors.

Section 4: The Future

Canada is on the cusp of a national crisis when it comes to LTC. Long wait times, limited provider infrastructure, large expenses, and overwhelmed caregivers are only some of the problems facing those needing LTC. As the examples of Germany and Japan prove, there are options for Canada as it deals with a rapidly increasing population of seniors and a growing demand for healthcare. The question is, what now? What can Canada and its private insurance industry do to help prepare for the oncoming crisis?

Creating a true social insurance system, lobbying for change, collaborating with private industry, educating the public, and providing choice are key steps that need to be taken to successfully deal with the future of LTC. The insurance industry is well positioned to help due to its global reach, large network of employees, and international knowledge base.

Social Insurance

Oxford’s definition of insurance is: “a practice or arrangement by which a company or government agency provides a guarantee of compensation for specified loss, damage, illness, or death in return for payment of a premium.”

Based on this definition, there is no public LTC insurance in Canada. In reality, there is a scheme that co-mingles tax-payer funds (premiums that are undefined in amount) for universal health care that is guaranteed, and LTC that is not guaranteed but expected. Care is provided if you are “sick enough”—determined through an unknown formula that is not transparent—and there is limited choice in where and how much care, so there are no real specified losses or damages.

One of the key success factors in both Germany and Japan is the dedicated insurance program, where funds are not shared or available to be moved to fund other programs. This would ensure that the LTC needs of the elderly are properly funded and trade-offs are not being made at the expense of universal healthcare or vice-versa. Canada would benefit from a similar dedicated LTC social insurance program.

Canada has experience with two insurance systems of this kind to draw from: namely, unemployment insurance and the CPP. These two social insurance programs are fully accepted and well understood in Canada. It is clear what funding is required, from whom, and what benefits will be provided. In addition, it is clear to most involved that these programs are insurance and not meant to be the only source of income protection, but a supplement.

This new social insurance system will only work with both public and private buy-in. Participation must be mandatory and positive results will need to be shared quickly to ensure support.

By working together and combining the knowledge of the insurance industry, the actuarial profession, public health care providers, and the government, Canada could successfully establish a social insurance program to deal with LTC needs.

Lobbying

Government reform is a critical step to improving the system in Canada. This is not and should not be a political issue. COVID-19 has highlighted to the general public that there are flaws in the system that local and federal politicians can’t ignore, but it has not highlighted all of the issues. While local governments are looking at reforms, the system needs to be looked at holistically, not piecemeal; and throwing money at the system without addressing the fundamental flaws is not the answer.

The insurance industry is uniquely positioned to help with the problems. Industry groups such as the Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association (CLHIA) and Canadian Association of Independent Life Brokerage Agencies (CAILBA) are highly respected in Canada and have the ear of government agencies. Together with life insurance companies that are focusing more on health outcomes versus simple claims payment, the industry has lobbying power with respect to Canadian’s health and well-being beyond the traditional financial health.

Given the global nature of many insurance companies in Canada, there is an opportunity to demonstrate the value that the insurance industry brings to the table in other countries where they do business. By sharing what has worked in those countries from an industry perspective, we can demonstrate the value of the partnership.

Collaborating With Private Industry

As seen in the international examples, the private industry—including health care providers and insurance companies—need to work collaboratively with the government and public providers for a more successful outcome. There needs to be ongoing discussions of what the legislation would look like from both angles and how better care can be achieved by working together. Insurance companies have a global presence which allows them to work with their colleagues in other countries to advocate for LTC solutions that have worked elsewhere.

The question many people will have is how this will be paid for. Insurance companies and actuaries can play a major role in structuring a prepaid fund and suggesting solutions for how to implement a self-sustaining solution that will work independently of any other healthcare subsidies while successfully anticipating future expenditures and needs [41]. The insurance industry can provide competitive options for care if subsidies were provided similar to Germany (many new options appeared once Germany had set up the new system) while working together with each other and the government.

Education

The first step to better care is to start with education. Right now, too many people believe that the universal health care system also covers LTC. People know that they want to stay at home in their aging years but do not know how to navigate the system or even what is available. This lack of knowledge about the current system, combined with the voluntary nature of LTC insurance in Canada, has led to a heavy reliance on publicly funded systems.

There is a lack of awareness in younger years that has partially led to the disappearance of private LTC solutions. The lack of knowledge, combined with the unpredictable nature of forecasting LTC, has led to even fewer insurance solutions [22].

One solution would be to use the thousands of insurance agents/advisors already in the industry as the front line of educators when it comes to LTC needs. They could help guide citizens in their younger years of what social insurance provides and the need for supplemental income to support their care as they age. The current approach of a “case manager determining if you qualify” lacks transparency and leads to patient dissatisfaction. Due to the fragmented patchwork of LTC services [1], there is no universal approach to educating Canadians on the need for a social insurance program.

Part of this overall education would include more engagement by all citizens as well as the understanding that while there is a public element to an LTC solution, individual responsibility, and savings remains important [41].

Embracing Competition and Innovation

The lack of a functioning social insurance program has led to intense regulation and limited choice and competition. Creating legislation that only transfers funds like the Canada Transfer Act of 2017 is not useful as it does not solve the issues of sustainability and healthcare needs. Change needs to be created with policy and effectively communicated to all groups involved, from labour unions to universities to medical professionals to regular citizens.

As seen in the German and Japanese examples, implementing a social insurance program naturally led to greater competition and innovation. The current system does not offer flexibility in how care can be delivered. By providing many different solutions and financing for people to choose from, new jobs will be created, quality control will naturally occur, and everyone will have choice and control over their own healthcare. This emphasis on home care instead of institutional care can only work with a financially sustainable program and a care provider infrastructure that is transparent and accountable.

SECTION 5: Conclusion

There are so many different aspects of the search for an LTC solution for Canada and this report has only scratched the surface. Any changes to LTC or the creation of a social insurance program will affect many branches of government including immigration, education, labour, and health. The solution to the LTC crisis will have far-reaching implications for all parts of Canadian society. This reinforces the importance of collaboration as the federal government can provide risk strategies and overall regulation but must respect the provinces’ “responsibility for program delivery” [20].

Collaboration must also exist between different levels of government and different groups within society itself. All Canadians must work together to create a financially sustainable program that is universal across all classes and all regions.

LTC has become a major financial and emotional strain on many Canadians and the system can no longer handle the needs. The population is aging quickly and there are fewer and fewer people to care for this aging population and less money to help fund the system. People are falling through the cracks and a universal LTC insurance plan is the only way to help these vulnerable members of our society.

In both Germany and Japan, it took a political catalyst before the country and its citizens made long-term care a priority. Unfortunately, Canada has not yet had that crisis.

The insurance industry should play an important role in guiding the legislation and the implementation of this system. They can use their influence, their knowledge, and their people to help the Canadian government create a strong integrated system that will ease pressures on current medical professionals and citizens.

One of the largest factors in the success of an LTC program in Germany was the idea of “social solidarity.” The culture of Germany has traditionally supported the idea of universal care within its communities. This is echoed by the approach in Japan and other countries. Canada also has this culture of providing for everyone which is seen in the universal health care system. It is time to take this system and enhance it with greater care for the most vulnerable members of Canadian society.

A successful LTC insurance program will be financially sustainable, it will protect all citizens, wealthy or impoverished, it will protect informal caregivers, and promote innovation and job creation. There are many LTC advocates pushing for change as soon as possible. The demographic changes that will occur in the next decade will be devastating for an already-strained healthcare system. We all have a role to play in this major cultural shift and insurance professionals can be a valuable and knowledgeable asset to the future changes to LTC in Canada.

The following steps are necessary to address the current challenges:

- Create a true federal social insurance system for LTC in Canada, with dedicated funding and clear benefits.

- Encourage home care as an option with subsidies for informal caregivers or caregivers of choice.

- Collaborate across government agencies, particularly labour, education, health, and immigration to address the lack of formal caregivers.

- Allow private sector competition with an easing of regulation to allow for choice and competition to create quality control.

- All of this needs to be coupled with an education component to assure citizens that this is in the best interest of society and the current system is not sustainable.

Works Cited

- Amaral, E., Jamieson, M., Cooper Reed, A., & Cameron, J. (2018-19), “The Implications of Self-Directed Home Care in Ontario: A Case Study on Gotcare Services,” The Reach Alliance. https://reachalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Gotcare-PolicyBrief-Final-Aug24.pdf

- Atal, J. P., Fang, H., Karlsson, M., & Ziebarth, N. R. (2021), “. Long-Term Health Insurance: Theory Meets Evidence.,” ZEW - Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper, 21, 1-47. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3989988

- Buescher, A., Wingenfeld, K, & Schaeffer, D. (2011), “Determining Eligibility for Long-Term Care - Lessons from Germany,” International Journal of Integrated Care, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.584

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), (2024). “Long-Term Care,” Canadian Institute for Health Information. www.cihi.ca/en/topics/long-term-care

- Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association (CLHIA). (n.d.), “A Guide to Long-Term Care Insurance,” Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association. www.clhia.ca/web/CLHIA_LP4W_LND_Webstation.nsf/resources/Consumer+Brochures/$file/Brochure_Guide_Long_Term_Care_ENG.pdf

- Canadian Medical Association (CMA), & Deloitte LLP. (2021, March 25), “Canada’s Elder Care Crisis: Addressing the Double Demand,” CMA Digital Library. https://digitallibrary.cma.ca/viewer?file=%2Fmedia%2FDigital_Library_PDF%2F2021%2520Canada%27s%2520elder%2520care%2520crisis%2520EN.pdf#page=1

- Cuellar, A. E. & and Wiener, J. M. (2000), “Can Social Insurance for Long-Term Care Work? The Experience of Germany,” Health Affairs, 19(3), 8–25. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.19.3.8

- Esmail, N. (2014, May 8), “Health Care Lessons from Germany,” Fraser Institute. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/health-care-lessons-from-germany

- Esmail, N. (2013, April 15), “Health Care Lessons from Japan,” Fraser Institute. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/health-care-lessons-from-japan

- Estabrooks, C. A., Straus, S. E., Flood, C. M., Keefe, J., Armstrong, P. Donner, G. J., Boscart, V., Ducharme, F., Silvius, J. L., & Wolfson, M. C. (2020), “Restoring Trust: COVID-19 and the Future of Long-Term Care in Canada,” FACETS, 5(1), 651–691. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2020-0056

- Feil, C., Yoon, B. C., Arulnamby, A., & Sinha, S. K. (2023, May 4), “Could a National Long-Term Care Insurance Program Be a Feasible Solution to Address Canada’s Growing Long-Term Care Crisis?” National Institute on Ageing. https://www.niageing.ca/long-term-care-insurance

- Flood, C. M., Dejean, D., Doetter, L.F., Quesnel-Vallee, A., & Schut, E. (2021), “Assessing Cash-For-Care Benefits to Support Aging at Home in Canada,” IRPP. Retrieved August 19th, 2024, from https://irpp.org/research-studies/assessing-cash-for-care-benefits-to-support-aging-at-home-in-canada/

- Giosa, J. L., Saari, M., Holyoke, P., Hirdes, J. P., & Heckman, G. A. (2022), “Developing an Evidence-Informed Model of Long-Term Life Care at Home for Older Adults with Medical, Functional And/or Social Care Needs in Ontario, Canada: A Mixed Methods Study Protocol,” BMJ Open, 12(8). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060339

- Government of Canada. (2024, June 5), Canada Health Act, . Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/canada-health-care-system-medicare/canada-health-act.html

- Government of Ontario. (2023, February 15), “Published Plans and Annual Reports 2022–2023: Ministry of Long-Term Care,” Government of Ontario. https://www.ontario.ca/page/published-plans-and-annual-reports-2022-2023-ministry-long-term-care

- Grosse, A., Kokorelias, K., Brierly, A., & Sinha, S. (2024), “Enhancing Care for Older Adults in Canada and ddown Under: What Canadian and Australian Long-Term Care Systems Can Learn from Each Other,” National Institute on Ageing. www.niageing.ca/australia2

- Home Care Ontario. (2024, March 15), “95% of Ontario Seniors Support Call to Immediately Increase Home Care Funding: Poll,” Newswire. https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/95-of-ontario-seniors-support-call-to-immediately-increase-home-care-funding-poll-875883889.html

- Home Care Ontario, (2024). “2024 Annual Report,” Home Care Ontario. https://homecareontario.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/2024-Annual-Report-FINAL.pdf

- HomeEquity Bank. (2023, June 6), “What Are Long Term Care Options for Retirees and How to Pay for it?” CHIP. https://www.chip.ca/reverse-mortgage-resources/retirement-planning/long-term-care/

- Hughes Tuohy, C. (2021, March 10), “Federalism as a Strength: A Path toward Ending the Crisis in Long-Term,” Centre of Excellence on the Canadian Federation. https://centre.irpp.org/research-studies/federalism-as-a-strength-a-path-toward-ending-the-crisis-in-long-term-care/

- Iciaszczyk, N., Neuman, K., Brierly, A., Macdonald, B., & Sinha, Samir. (2024, January 31), “Perspectives on Growing Older in Canada: The 2023 NIA Ageing in Canada Survey,” National Institute on Ageing. https://www.niageing.ca/2023-annual-survey.

- Joshua, L. (2017), “Aging and Long-Term Care Systems: A Review of Finance and Governance Arrangements in Europe, North America and Asia-Pacific,” World Bank. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/761221511952743424/aging-and-long-term-care-systems-a-review-of-finance-and-governance-arrangements-in-europe-north-america-and-asia-pacific.

- Karmann, A. & Shinya S. (2021). Comparison of the Japanese and German Nursing-Home Sectors: Implications of Demographic and Policy Differences. SSRN Electronic Journal. Retrieved August 19th, 2024, from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3814576

- Kokorelias, K. & Flanagan, A. (2023, August). NIA Research Proposal to Create a Virtual Long-Term Care @ Home Program Shortlisted to Receive Inaugural Hunter Prize for Public Policy. National Institute on Ageing. https://www.niageing.ca/bringing-longterm-care-home-copy-hunter-prize

- Kralj, B. & Sweetman, A. Residential Care Sector Personal Support Worker (PSW) Work Force: Characteristics, Trends and Projections. AgeWell. https://agewell-nih-appta.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/PSWs_ResCare_Merged.pdf

- Labrie, Y. (2021, October 8). Canada’s Long-Term Care System Lacks Choice and Competition: Op-Ed. Fraser Institute. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/article/canadas-long-term-care-system-lacks-choice-and-competition

- Labrie, Y. (2022, February 24). Ontario Government Ties More Red Tape around Long-Term Care. Fraser Institute. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/article/ontario-government-ties-more-red-tape-around-long-term-care/

- Labrie, Y. (2021, October 5). Rethinking Long-Term Care in Canada: Lessons on Public-Private Collaboration from Four Countries with Universal Health Care. Fraser Institute. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/rethinking-long-term-care-in-canada

- Library of Parliament. (2020, October 22). Long-Term Care Homes in Canada – How Are They Funded and Regulated HillNotes. https://hillnotes.ca/2020/10/22/long-term-care-homes-in-canada-how-are-they-funded-and-regulated/

- MacDonald, B., Wolfson, M., & Hirdes, J. P. (2019, October). The Future Co$T of Long-Term Care in Canada. National Institute of Ageing. https://www.nia-ryerson.ca/s/The-Future-Cost_SC_Oct6_FINAL.pdf

- Manuel, D. G., Garner, R., Fines, P., Bancej, C., Flanagan, W., Tu, K., Reimer, K., Chambers, L. W., & Bernier, J. (2016). Alzheimer’s and Other Dementias in Canada, 2011 to 2031: A Microsimulation Population Health Modeling (POHEM) Study of Projected Prevalence, Health Burden, Health Services, and Caregiving Use. Population Health Metrics. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-016-0107-z

- Milligan, K. S. & Schirle, T. (2023, November). The Economics of Long-Term Care in Canada. National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved August 19th, 2024, from https://www.nber.org/papers/w31875

- Morel, N. (2013, May 17). Providing Coverage against New Social Risks in Bismarckian Welfare States: The Case of Long-Term Care. Hal.science. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-00823686v1

- Nadash, P. (2020). The Evolution of Long-Term Care Programs Comment on “Financing Long-Term Care: Lessons from Japan. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 9(1), 42–44. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2019.79

- Nadash, P., Doty, P., & von Schwanenflugel, M. (2017) The German Long-Term Care Insurance Program: Evolution and Recent Developments. The Gerontologist, 58(3), 588-597. https://academic.oup.com/gerontologist/article/58/3/588/3100532

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2023). Health at a Glance 2023. OECD Library. https://doi.org/10.1787/7a7afb35-en

- Roberts, R. L., Bartram, M., Kalenteridis, K., & Quesnel-Vallee, A. (2021). Improving Access to Home and Community Care: An Analysis of the 2017 Health Accord. Health Reform Observer, 9(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.13162/hro-ors.v9i1.4367

- Statistics Canada. (2022, April 27). A Portrait of Canada’s Growing Population Aged 85 and Older from the 2021 Census. Statistics Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-X/2021004/98-200-X2021004-eng.cfm

- Tamiya, N., Noguchi, H., Nishi, A., Reich, M. R., Ikegami, N., Hashimoto, H., Shibuya, K., Kawachi, I., & Campbell, J. C. (2011). Population ageing and wellbeing: lessons from Japan’s long-term care insurance policy. The Lancet, 378(9797), 1183-1192. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61176-8

- Theobald, H. (2012). Combining Welfare Mix and New Public Management: The Case of Long-Term Care Insurance in Germany. International Journal of Social Welfare, 21(s1), S61–S74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00865.x

- Theobald, H. & Hampel, S. (2012). Disruptive Institutional Change and Gradual Transformation: Long Term Care Insurance in Germany | International Long-Term Care Policy Network ILPN. International Long-Term Care Policy Network. https://www.ilpnetwork.org/wp-content/media/2012/08/w_06_1530_Theobald.pdf

- Traphagen, J. W. & Nagasawa, T. (2008). Group homes for elders with dementia in Japan. The Journal of Long-Term Home Health Care, 9(2), 89-96. https://doi.org/10.1891/1521-0987.9.2.89

- Woolley, F. (2023, October 25). Long-Term Care Financing: What’s Fair and Sustainable? Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP). https://irpp.org/research-studies/long-term-care-financing-fair-and-sustainable/