Bridging the retirement income protection gap - Tomorrow’s challenge but today’s opportunity

by David Lipovics, Vice President, U.S. Pension Risk Solutions, RGA

1. A protection gap less-talked-about

Few could dispute that many of the world’s largest economies have aging populations. With public and empoyer-sponsored pension systems gradually decreasing in scope and significance, the elderly increasingly must shoulder the burden of saving adequately for their retirement years. It is a challenge many underestimate and do not adequately prepare for.

The provision of guaranteed lifetime income is one of the most fundamental functions life insurance products can perform. Yet, incomplete risk awareness on the part of retirees, coupled with rather spiritless product development efforts on the part of life insurers, mean that the lifetime retirement income market is only a fraction of what it could, and arguably should, be.

Statistics for the three largest retirement markets, the U.S., the U.K., and Japan, show a worrying disparity between the size of retirement savings individuals accumulate and the proportion of these savings safeguarded by guaranteed lifetime retirement income insurance products. The magnitude of the resulting protection gap will only become evident over decades – and at that point, it will be too late.

The time to address this challenge is now. Understanding and responding to this gap is not just an economic and societal imperative but also a significant opportunity for life insurers.

1.1 Basic view of retirement systems

The retirement systems of most economies are similar. While structural details and naming conventions undoubtedly differ, typical retirement systems have the following stakeholders that are consistent across regions:

- The State: In a government-backed retirement program, a social safety net is intended to ensure that citizens have a minimum level of income after they stop working.

- Employers: In a Defined Benefit (“DB”) market, pension plans are usually funded entirely by employers, and the responsibility for investment and management of the funds (including making sure that the funds last as long as retirees live) also rests with employers.

- Individuals: In a Defined Contribution (“DC”) market, employees and employers contribute funds to individual retirement accounts. Employees bear the investment risk of their accounts and outliving their savings. They are also generally responsible for making all financial decisions up to and throughout retirement.

Importantly, these stakeholders are not equal in their relevance and significance in today’s retirement systems – and that inequality will increase even more in coming years. Due to the burden public pension systems place on a nation’s finances, most governments have been gradually decreasing the generosity of state pension benefits. Currently, few doubt the unsustainability of government-backed pension systems. Similarly, defined benefit plans put a considerable financial burden on employers, making these plans less common in recent years.

With such tectonic shifts in two out of the three fundamental sources of retirement income, the retirees of tomorrow will be left increasingly on their own to secure adequate financial resources in retirement.

1.3 Rising to the challenge: the role of life insurers

The protection needs of current and future retirees are something the life insurance industry should pay close attention to. By 2030, 1 in 6 people in the world will be aged 60 years or over[i].

Life insurers in most insurance markets offer lifetime income protection products to employer-sponsored defined benefit pension plans (in the form of group annuity products, sold as part of pension risk transfer transactions) as well as to individuals (in the form of individually sold lifetime annuities). The market for individuals is much less developed and much less active. This should raise significant concerns as the absence of an active market for individuals directly contributes to a growing protection gap for current and future retirees.

2. Three continents – the same challenge

Despite the many differences between respective pension constructs, economic outlooks, and life insurance industries, the three largest pension systems all share the same challenge: Retirees are not buying the lifetime income protection they will most likely need. While discussion here is confined to the U.S., the U.K., and Japan, these observations extend well beyond these three specific countries and reflect global trends that are either already relevant or will inevitably become relevant in most insurance markets.

In the U.S., U.K., and Japan, individual retirees already hold more than twice as much in pension savings as private corporations[1]… whether it will last them all the way through retirement is a challenge for the next decades.

2.1 Individual retirement assets on the rise

In line with the gradual decline of DB plans offered by employers as a means of guaranteed retirement income, the DC markets have risen in prominence. At the end of 2020, more than $10 trillion in assets were invested by individuals in retirement accounts across these three largest retirement markets globally, covering close to 100 million future retirees (see Table 1).

This represents the amount of funds that individual savers have accumulated, and continue to accumulate, specifically for the purposes of having adequate financial resources in retirement. Across these three countries, individual retirees already hold well over twice as much in the dollar value of their assets as private corporations[ii] – a ratio that is only set to increase as the DC markets grow and become the predominant form of retirement planning.

Table 1

| Location | Number of individuals holding retirement accounts | Size of individual retirement account assets (in USD trillions) | |

| 2020 | 2030 (Projected) | ||

| United States[iii] | 60 million | $9.4 | $13.0 |

| United Kingdom[iv] | 28 million | $1.0 | $1.3 |

| Japan[v] | 8 million | $0.1 | $0.3 |

Size, however, is, at best, only half of the story. Nested in retirement accounts, the more than $10 trillion of assets, while sizable, leave individuals with little protection against the risk of outliving their savings, or more broadly, the risk that their retirement income significantly differs from expectations. The risks are particularly acute for the at-retirement population, i.e., individuals that have stopped working and thus contributing to their retirement accounts and are about to enter the decumulation phase.

The choices made at this juncture can be hugely impactful for future financial well-being. One of the important choices becomes how much, if any, retirement savings to contribute towards guaranteed lifetime income products offered by the life insurance industry.

2.2 The value of guaranteed lifetime income

Guaranteed lifetime annuities hold significant value for individuals seeking financial security and stability during retirement. Several studies show[vi] that an optimal portfolio of products and investments in retirement should contain an element of guaranteed lifetime income – most likely in the form of a lifetime annuity.

Currently, a 66-year-old man is expected to live for a further 19 years, but one in 10 can expect to survive until age 95. In comparison, a 66-year-old woman will likely live an additonal 21 years, with one in five making it to age 95[vii]. It is a risk not many individuals realize, let alone know how to protect against.

Lifetime annuities provide a steady and reliable stream of income that lasts for the rest of the annuitant's life, thereby mitigating an individual’s exposure to risks arising from their own longevity as well as general investment performance. By converting a portion of their assets into an annuity, retirees transfer the risk of living longer than expected to an insurer.

2.3 Lifetime annuities are rarely purchased

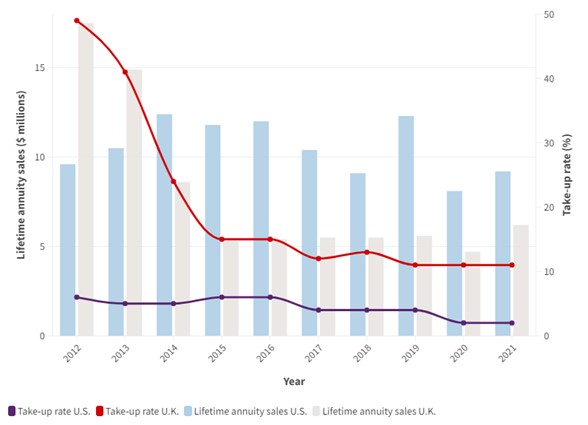

Given the massive market sizes and the theoretical appeal of guaranteed lifetime income products, sales volumes in this corner of life insurance market are staggeringly low. Chart 1 below shows the take-up rate of guaranteed lifetime annuity products across different geographies; specifically, it examines the proportion of defined contribution asset withdrawals that go towards the purchase of guaranteed lifetime income products.

Chart 1: Individual Lifetime Income Protection Sales and Take-up Rates in the U.S. and the U.K.

Observations are generally consistent across regions:

- Individuals allocate very little of their retirement savings towards life insurance products that protect against the risk of outliving their savings. In the U.S. in 2021[viii], of the $385 billion of DC withdrawals, less than $10 billion (or 2%) was used to purchase lifetime annuity products. Similarly, in the U.K.[ix], with nearly $60 billion in withdrawals, approximately $6 billion (or 11%) had been used to buy guaranteed income protection.

- The take-up rate of lifetime annuity products has been slowly declining in recent years, even as overall defined contribution withdrawals have been increasing. Over the last five years, the proportion of DC distributions used to buy lifetime annuities declined in both the U.S. and the U.K, from 6% to 2% and 15% to 11%, respectively. These drops are made even more dramatic by the fact that the amount of DC distributions have in fact increased significantly in the last five years. In the U.S. alone, the at-retirement population distributed around $215 billion from their DC accounts in 2016, while the corresponding figure in 2021 was $385 billion (an 80% increase). In other words, even as DC accounts mature and more people with DC accounts retire, the appeal and take-up of lifetime income protection appears to fall consistently.

- It is worth highlighting that the substantial drop in both sales and take-up rates in the U.K. in the 2012 to 2015 period was driven by a change in legislation whereby compulsory annuitization, i.e., the mandatory purchase of a lifetime annuity from DC proceeds at reirement, was abolished by the government.

- It is worth highlighting that the substantial drop in both sales and take-up rates in the U.K. in the 2012 to 2015 period was driven by a change in legislation whereby compulsory annuitization, i.e., the mandatory purchase of a lifetime annuity from DC proceeds at reirement, was abolished by the government.

- While data sources with comparable granularity for Japan are limited, the observations made in respect to the U.S. and the U.K. appear consistent with the Japanese lifetime annuity market. Specifically, the take-up rate of lifetime annuity options hovered around 4-7% in a study period roughly 5 years ago.[x]

2.4 Where do retirement savings go?

Clearly, most retiree funds do not get used to purchase lifetime income protection. Instead, an alarming share of the at-retirement population decides to manage longevity and investment risks on their own.

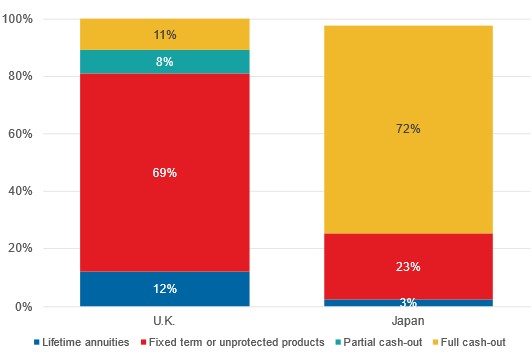

Looking at the most recent DC withdrawal statistics from the U.K. covering funds distributed in 2022, almost 20% of the withdrawals were cash payouts, while close to 70% were roll-overs into other ‘unprotected’ products (most notably, income drawdown policies). This means close to 90% of the funds being used in a way that foregoes the lifetime income protection that could have been provided by lifetime annuity products. The picture in Japan looked equally bleak a few years ago[xi]: An overwhelming majority of retirees took a cash lump sum (72%) or ‘unprotected’ products (23%) instead of lifetime annuity options (3%). Data shared below illustrates this trend:

Chart 2: Benefit-Type Choices at Retirement in the U.K. and Japan

2.5 The emerging protection gap

The risky decision to forego insurance protection contributes to a growing lifetime income protection gap that will only become apparent years from now.

That a sizable gap exists, though, is beyond question. To illustrate, simply consider the following shortcomings of strategies that rely exclusively on the consumer making both income withdrawal and ongoing investment decisions:

- Indivuals routinely underestimate their own life expectancy – by a median two years in the U.S.[xii]

- Even if using correct estimates, outcomes from an income drawdown strategy predicated on an individual’s life expectancy can vary significantly. For example, the estimated length of time a given pot of retirement funds is expected to last can fluctuate by as many as 5-7 years under moderately adverse vs. favorable market movements and mortality outcomes.[xiii]

The average retiree is ill-equipped to deal with the risks of an unprotected retirement income strategy.

3. In search of a missing market

With trillions of retirement funds at play and evident consumer needs, the guaranteed lifetime income market should, in theory, present a huge market opportunity for life insurers. Why, then, is this market segment so consistently anemic across different geographies? This question deserves closer analysis and a degree of self-reflection by the life insurance industry and its policymakers.

A few potential root causes, which are distinct in nature but with amplifying interactions, can explain, at least in part, the underperformance of lifetime annuity markets.

The individual retirement markets of the U.S., the U.K., Japan, and indeed, most countries with meaningful private pension systems, are not organized to support a smooth transfer between the accumulation (i.e., pre-retirement savings) and decumulation (i.e., post-retirement spending) phases of retirement. In fact, there are almost always defined end dates to the frameworks under which individuals approaching retirement save (such as 401(k) plans in the U.S. or employer DC schemes in the U.K.). These end points, often unexpectedly or prematurely, force individuals to decide what to do with their lifetime savings. Those decisions, as shown in section 2.4 above, rarely result in balanced, well-considered financial choices, but instead predispose the average saver towards the “path of least resistance” – taking a cash lump sum and/or rolling funds into an ‘unprotected’ product.

By contrast, the purchase of a lifetime annuity would necessitate a conscious effort to withdraw funds and independently search for a suitable product to channel money into. The importance of this deceptively small discontinuity should not be understated.

A further characteristic of most defined contribution pension systems is that they are heavily fragmented, with limited portability between individual plans. The regulatory framework is simply not there. As most savers have multiple employers during their careers, so do they have multiple pension pots in their portfolio at retirement. As evidence suggests[xiv], the smaller the amount, the more likely it is to be fully withdrawn as cash.

3.2 Customer awareness and behavior

Innate customer behavior coupled with a lack of high-quality information around prudent retirement strategies, contribute to low lifetime annuity take-up rates. Several academic studies[xv] discuss the behavioral economic calculus of annuitization decisions upon retirement. Essentially, most consumers exhibit loss averse behaviors and have distorted views of probabilities, underestimating the chances of high-probablity events (such as surviving to a very old age) and overestimating the chances of low-probability events (such as dying at a young age). The combination of these biases makes handing over large sums of money that will only pay off at very old ages seem counter intuitive.

The U.K. provides a vivid illustration of how customers change their behavior if left to their own devices. In 2014, the U.K. government implemented significant changes in the basic structure of the lifetime annuity market, effectively eliminating the requirement for the at-retirement population to use a portion of their pension pot to purchase lifetime annuities. As shown in Chart 1, a full year after policy implementation, the lifetime annuity take-up rate dropped from 41% in 2013 to 15% in 2015 – and it has never recovered since.

Even more revealing, recent studies show a clear relationship between getting financial advice and the purchase of a lifetime annuity. Roughly two-thirds of all retirees who decide to make full cash withdrawals of their pensions did not seek any kind of financial advice before making the decision. By contrast, two-thirds of those who decided to purchase annuities did seek financial advice[xvi].

3.3 Product pricing and development

It is hard to break the spell of low sales volumes. The smaller the pool of retirees who choose to purchase lifetime annuities, the higher the risk of anti-selection from the point of view of life insurers, making the product more expensive and perpetuating the perception that annuities are not good value for money. Indeed, most life insurers are forced to assume that only the highest-risk individuals (i.e., those from the highest socioeconomic groups) who have also sought financial advice, will decide to purchase lifetime annuities. This makes the product disproportionately expensive for less affluent individuals who need financial security most.

The historically low interest rate environment that has characterized global economies over the last 10-15 years, amplified the negative perception of lifetime annuities. Given the low average investment yield on long-term investments insurers would typically use to back annuity reserves, the level of lifetime income that a given pot of retirement savings can guarantee has appeared rather low. Insurers, of course, have various ways to access investment opportunities that are not available

to individual investors, however to make good business sense, insurers need scale for such investments. With lifetime annuity volumes as low as they are, such scale is, to a large extent, elusive.

4. A promising template in another market segment

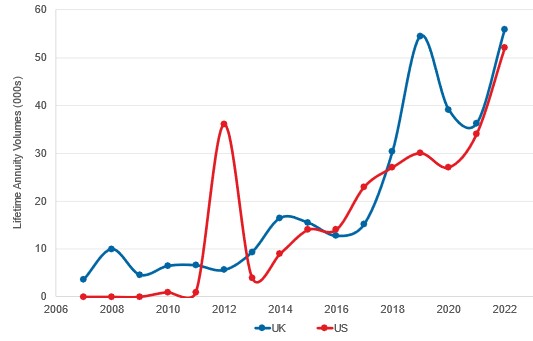

While the individual lifetime income market has been sluggish, a parallel market segment has been enjoying explosive growth. Employers have been purchasing guaranteed lifetime income protection for their DB pension plans at record rates in both the U.S. and the U.K. This is often referred to as Pension Risk Transfer (“PRT”). For PRT, the underlying life insurance product is essentially the same as a guaranteed lifetime annuity, with the exception that it is purchased by a corporation for a group of retirees.

The success of the international Pension Risk Transfer markets may offer learnings for expanding individual guaranteed lifetime income markets.

The success of the international PRT markets may offer approaches that may be applicable for expanding individual guaranteed lifetime income markets. Spending time examining these markets more closely could be worthwhile for both policymakers and life insurers aspiring to address the retirement income protection gap.

4.1 Recent DB market developments

Although not quite as large as the individual retirement (i.e., defined contribution) market, the institutional lifetime annuity (i.e., DB) market encompasses a significant amount of assets – roughly, $3.7 trillion in the U.S.[xvii], $1.8 trillion in the U.K.[xviii] and $0.7 trillion in Japan[xix]. Institutions (typically corporate sponsors of DB pension plans) have been purchasing guaranteed lifetime income protection for their retirees at volumes that far exceed the comparable sales volumes in the individual retirement market. These volumes have been trending heavily upwards in recent years.

Chart 3 below shows the annual sales of group lifetime annuites in the U.S.[xx] and the U.K.[xxi] over time. In the last five years alone, the markets have grown by annualized rates of 18% and 27% in the U.S. and the U.K., respectively. These results stand in stark contrast to the pattern of stagnation, followed by decline in the corresponding individual lifetime annuity sales shown, previously, in Chart 1.

Chart 3: Group Lifetime Annuity Volumes

4.2 Favorable conditions for growth

A conducive regulatory framework, effective communications and promotion of the value group lifetime annuities bring, and concerted product development can all contribute to the rapid growth of the PRT market. Specifically;

- In most large life insurance markets (although notably not in Japan), there is a clear regulatory framework that governs how corporations should engage the insurance industry so insurers can offer lifetime income protection to retired employees. Equally important, the benefits of purchasing this insurance protection are immediately recognized on the corporate balance sheet through lower liabilities, income volatility, and governmental levies.

- Large financial services firms specialize in giving advice and providing brokerage services to corporations contemplating the purchase of group annuities. Not only are these corporations sophisticated customers and investors to begin with, but they are also aided by qualified advisors who help measure and advocate for the value of purchasing protection from the life insurance industry.

- Given the growth potential and increasing sales volumes in this market segment, life insurers have invested considerable resources indeveloping attractive group annuity products. Pricing for the longevity risk inherent in these products is made simpler by the product’s ‘socialized’ nature, that is, a corporation is purchasing protection for all retirees under one policy and therefore potential anti-selective behavior by individual retirees is eliminated.

- To counter the generally low interest rate environment, insurers can increase investment allocations towards “alternative” asset classes, such as those that are not publicly traded. Healthy sales volumes brining more funds allow insurers to invest in these higher-yielding asset classes at scale and provide annuity pricing that is attractive.

4.3 What might one market learn from the other

Drawing close comparisons between two distinct markets could be overly simplistic. Nevertheless, given the similarity between the underlying insurance needs and insurance products, the structure and operation of the group lifetime annuity market do offer valuable lessons to the individual lifetime annuity market. These lessons, if acted upon, could potentially increase the willingness of the at-retirement population to purchase guaranteed lifetime income protection and thus narrow the current retirement income protection gap.

Comprehensive legislation / regulation that targets individual retirement savings

A fundamental, yet often missing, requirement is a legal and regulatory framework that combines the accumulation and decumulation phases of retirement into a coherent whole. This should be an area of focus for policymakers. As noted earlier, individual savers, due to the discontinuity between (i) employer sponsored DC retirement accounts, and (ii) the insurance and savings products that are available to the same individuals in their retired years, are often forced into binary decisions at retirement (e.g., withdraw a lump sum or purchase an annuity). These discrete decision points predispose individuals towards the “default option”, which in most markets is the withdrawal of cash lump sum(s).

To combat this discontinuity, employers could be allowed to embed lifetime annuity products in their defined contribution plans. With the appropriate structural changes, DC plan members should be able to purchase lifetime income protection either while they are saving for retirement or at-retirement, all through their DC plans. This would necessitate close alignment and coherence between rules and regulations that govern DC plans and those that govern insurance products and how they are sold – much as is the case of DB plans and the group annuity market.

A promising development is recent legislation that was passed in the U.S. in 2022. The SECURE 2.0 Act aims to pave the way for insurer-carried annuity products to enter the realm of employer-sponsored DC plans such as 401(k)s.

Giving a more prominent role to employers

Arguably the decommissioning of employer-sponsored DB plans has caused the pendulum to swing from one extreme to the other. Where once employers were fully on the risk for their retirees’ lifetime income security, the rise of DC plans has transfered the risks to their retired employees. Employers now only provide the infrastructure for retirement savings vehicles which are otherwise independent from them.

Building on the coherent legal and regulatory framework envisioned above, employers should be encouraged (perhaps through tax or other corporate incentives) to consider implementing group lifetime income protection products as part of their DC plans. This would be conceptually similar to group life or health insurance policies already commonly purchased by employers for their workforces. These policies allow individuals to benefit from the collective bargaining power and diversification of the group but also allow employees to customize certain policy features for themselves.

Combating behavioral biases

Perhaps the hardest nut to crack is figuring out if and how various stakeholders of the retirement income market (the state, employers, insurance companies, etc.) should counteract the tendencies of individual retirees to not purchase lifetime income protection products. In the DB market, the value of transferring retirement obligations to the insurance industry is widely recognized and publicized. As for changing individual attitudes, the solution is easy: individual retirees are not given a choice, the DB plan sponsor buys protection on their behalf.

A softer approach that is applicable to the DC space could be a group retirement income policy, as discussed above, that is purchased by a past or present employer but that offers individual, customizable features. Even softer still, employers may nudge savers toward desirable outcomes by selecting for them default options for their defined contribution funds. For instance, it is already common practice for DC contributions to be channeled into specific investment funds (such as target date funds) driven by the saver’s normal retirement date. It would not be much of a stretch to imagine a certain amount of an individual’s retirement account being, by default, directed towards the purchase of a guaranteed lifetime income option. Individuals, of course, can always opt out of the default settings.

At a minimum, however, improving customer financial awareness and the role of qualified financial advice should be emphasized. The U.S., the U.K., Japan and other countries will have their own views based on cultural and political differences as to the right level of customer education. However, it is clear all of these markets can and should do more.

Turning a vicious cycle into a virtuous one

Low sales volumes in a market discourage product development and result in products that are less attractive despite their potential for providing strong protection. This is keenly true in the individual lifetime annuity market. However, by pursuing initiatives to increase product take-up rate, this trend can be broken.

Giving more prominence to employer choices on behalf of their employees, as opposed to individuals, would help broaden the mix of annuitants and thus reduce the anti-selection premium that is currently priced into most lifetime annuity products.

Similarly, any measure that increases the size of the market will help focus insurers’ attention on enhancing product offerings. Being able to rely on a larger inflow of annuity premiums allows insurers to invest at scale and in a manner that ultimately makes pricing more attractive. It is evident in the success of the DB group annuity market that once scale kicks in, pricing attractiveness gets a boost.

With flexible product design, insurers could also help ease retirees’ anxiety about handing over part of their life savings. For example, consider Single Premium Immediate Annuities (“SPIA’s”) in the U.S.

A common feature of SPIAs is a premium refund guarantee. If the annuitant dies in the first few years of policy issuance, their estate receives a refund of premium adjusted for the annuity income already paid out. From the annuitant’s perspective, this product feature allays the fear of dying soon after the annuity commencement date and foregoing the value of the lifetime income guarantee. From the insurer’s perspective, this is a relatively inexpensive product feature to offer because the cumulative probability of the annuitant dying in the first few years of the policy is low. In other words, a win-win and a great example of the type of product development that serves the needs of the market at large.

5. Call to action – closing the retirement income protection gap

With the gradual, most likely irreversible, decline in the role of the state and of employers in providing financial security to retirees, the onus is on individuals to make the right financial choice leading up to, and at, retirement. However, the average retiree across the three largest global retirement systems is alarmingly underprepared for the financial risks they will face in retirement. The lifetime income protection gap looms large and will only continue to grow unless current trends are broken or reversed – bridging it is a societal and financial imperative for most developed economies.

The life insurance industry could and should play a major role. Building upon an existing product suite and expertise, life insurers are better placed than anyone to partner with policymakers to advance a retirement income protection agenda, taking best practices and learnings from related markets and across geographies.

Make no mistake – catalyzing the individual lifetime income market represents a unique growth opportunity, too. Selling lifetime income protection products with an attainable market of close to $10 trillion and close to 100 million potential customers should be an enticing prospect.

[i] World Health Organization: Ageing and Health, online article published 1 October 2022 (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health)

[ii] See combination of iii, vii, xvi and xvii

[iii] PwC: Retirement in America: Time to rethink and retool; 2021 (https://www.pwc.com/us/en/industries/financial-services/library/retirement-in-america.html#:~:text=A%20range%20of%20factors%20have,structural%20and%20unlikely%20to%20ease)

[iv] Bank of England: A Roadmap for Increasing Productive Finance Investment; 2021 (https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/report/2021/roadmap-for-increasing-productive-finance-investment.pdf?la=en&hash=F92ADDFB1B815895AAFCC21CE6A29C5B0A74D6B7)

[v] Fidelity International: Defined Contribution Plan Reform Proposal for Japan - Enhancing private pension systems; 2020 (https://www.fidelity.co.jp/static/japan/pdf/dc-research/DC_ResearchVol1_en.pdf)

[vi] American Academy of Actuaries: Lifetime Income Initiatives; Retiree Lifetime Income: Choices & Considerations; 2015 (https://www.actuary.org/sites/default/files/files/Risky-Business-Retiree-Lifetime-Income-Choices-and-Considerations.pdf)

[vii] Institute for Fiscal Studies: Challenges for the UK pension system: the case for a pensions review; 2023; (https://ifs.org.uk/publications/challenges-uk-pension-system-case-pensions-review)

[viii] RGA calculations using 1) Congressional Research Service: U.S. Retirement Assets: Amount in Pensions and IRAs; 2022 (https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12117/2) and 2) Secure Retirement Institute (SRI) U.S. Individual Annuity Sales Survey

[ix] Financial Conduct Authority: Retirement income market data 2021/22; 2022; (https://www.fca.org.uk/data/retirement-income-market-data-2021-22#full)

[x] The Life Insurance Association of Japan; For the realization of a safe and secure

[xi] The Life Insurance Association of Japan; For the realization of a safe and secure society; 2015 (http://www.seiho.or.jp/info/news/2015/pdf/20151120.pdf)

[xii] Stanford Center on Longevity: Underestimating Years in Retirement; (https://longevity.stanford.edu/underestimating-years-in-retirement/)

[xiii] Institute and Faculty of Actuaries: The future of the individual annuity market (as presented by Karen Brolly and Sean James of Hymans Robertson) at the November 2019 Life Conference

[xiv] Financial Conduct Authority: Retirement income market data 2021/22; 2022; (https://www.fca.org.uk/data/retirement-income-market-data-2021-22#full)

[xv] Anran Chen: The impact of behavioral factors on annuitisation decisions and

decumulation strategies; 2017; (https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/18195/1/Chen,%20Anran.pdf)

[xvi] Financial Conduct Authority: Retirement income market data 2021/22; 2022; (https://www.fca.org.uk/data/retirement-income-market-data-2021-22#full)

[xvii] Congressional Research Service: U.S. Retirement Assets: Amount in Pensions and IRAs; 2022 (https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12117/2)

[xviii] UK Office for National Statistics; Funded occupational pension schemes in the UK: July 2019 to December 2022; 2022

[xix] Investment Company Institute; The Japanese Retirement System; 2021 (https://www.ici.org/system/files/2021-12/21_bro_japanese_retirement.pdf)

[xx] Secure Retirement Institute (SRI) U.S. Group Annuity Sales Survey

[xxi] Hymans Robertson: Risk Transfer Report 2023; 2023