Be yourself, more… with skill (Goffee and Jones)

An exploration of the essentials of good leadership

by Alexandra Chittock, Executive Director Specialty Casualty, Gallagher Re

What is leadership and who should be doing it?

“Leadership is not about titles, positions or work hours… it’s about relationships”, Jim Kouzes.

Typing ‘leadership’ into Amazon produces more than 100,000 book titles – an entire industry of leadership development and associated expertise grows exponentially as organisations pursue the unique and differentiating qualities that attract, engage and retain the best talent to establish their business as the market leader.

Leadership is certainly essential to a company’s strong performance, but what exactly is it and how do you do it well?

This paper sets out to explore three facets of leadership – firstly, to address the difference between leadership and management, which are often conflated in practice when they should be distinguishable. Secondly, to explore some of the qualities of successful leaders and thirdly, to consider women and leadership, highlighting differences in style and characteristics that may benefit from attention by current leadership in organisations, and which may not yet have enough recognition or appreciation.

The paper ends with some recommendations for improving leadership skills and draws conclusions on the subject.

Leadership and Management

Often confused with management, John P. Kotter notes several key differences between leadership and management. “Management and leadership both involve deciding what needs to be done, creating networks of people to accomplish the agenda, and ensuring that the work actually gets done. Their work is complementary, but each system of action goes about the tasks in different ways.”1 Leadership is concerned with aligning people around a shared vision through effective communication, inspiring people to engage with change and setting culture and direction. Management provides an orderly framework to produce consistent, risk-free outcomes – an agenda built around sourcing people for the right roles and monitoring their performance to implement a prescribed plan.

Historically, organisations have relied on hierarchy to create role clarity – none more so than in the armed forces where status, role clarity and task implementation are often executed under pressure and where decisions by leaders and managers alike may be literally a matter of life and death. The British Army’s book “The Queen’s Commission, A Junior Officer’s Guide”

asserts that “the art of leadership and the science of management is considered essential to the successful exercise of command at all levels.”2

If leadership is concerned with setting vision and direction, does this make it the sole preserve of those in the senior echelons of an organisation? Keeping with examples from the military, such rigid hierarchical structures might suggest leadership only flows from the top; however, the very opposite is true with leadership being essential at all levels and ranks, enacted through ‘mission command’. The need for fast, nimble responses in the face of adversity requires decentralised command and freedom of action, supported by mutual understanding and initiative at all levels, nurtured by good leadership and balanced by sound management.3 In fact, Bill George, former CEO of Medtronic plc and Harvard Business School professor advocates that experience is more important than education for honing leadership skills, and it is essential to open up as many leadership opportunities as early as possible to build successful corporations.4

Qualities of effective leaders and what makes them successful

To understand effective leadership qualities, it is important to consider what constitutes success in this context. For corporate enterprises, increased profitability and share price would seem obvious metrics; however, over what time horizon and at what cost? Certain actions may yield short term financial gain, but ultimately destroy employee and stakeholder loyalty, resulting in longer term decline.

From 1996 to 2001, Enron was awarded the title of ‘America’s Most Innovative Company’ six years in a row. Enron showed exceptional performance across all financial metrics, with CEO Jeffrey Skilling widely praised for his authoritative, charismatic, and evidentially effective leadership style. In hindsight, whilst Jeffery Skilling’s leadership style may have been effective, it did not lead to successful outcomes.

Stereotypical leadership qualities include charisma, authority and self-confidence; however, these are also characteristics of toxic leadership5. Toxic leaders tap into their followers’ deep-seated psychological motivations exploiting their followers’ basic needs, such as the need for authority, security, to belong and to feel special alongside their primal fears, such as the fear of ostracism and powerlessness. These fears explain why toxic leaders stay in power, because followers fear being shunned for speaking out and are unable to calibrate the feelings of others due to the success of suppressing dissent.6 As economic results and success are not the same, effective leadership in the corporate context clearly requires a level of morality. Current leadership thinking seems to be turning towards the establishment of cultures built on psychological safety7, perhaps as an antidote to the stereotypical leadership status quo above.

Rob Goffee and Gareth Jones assert that great leaders act as “authentic chameleons” transitioning through a variety of roles and challenges whilst consistently showing their true selves. Authenticity is of greater importance today due to shifting attitudes contributed to by the series of corporate failures and scandals such as Enron, Worldcom, Tyco, Bernie Madoff and HealthSouth produced by excessive individualism and narcissism.8 In his book ‘The Trusted Advisor’ David Maister proposed a ‘trust equation’, defining a person’s perceived trustworthiness as one that demonstrates high levels of credibility, reliability and intimacy (personal connection) and low levels of self-interest (or orientation).9 The impact of such high-profile business crashes circa 2008 perhaps inciting a call for leaders who behave with integrity, operating as citizens in service of others, rather than individuals in pursuit of personal gain.

Becoming an authentic leader is one thing, but leaders need followers, and followers need to be able to identify who a leader is and to understand their values, in order to feel motivated and energised to support their direction. Goffee and Jones state the importance of self-declaration and the ability to identify individual values and purpose, in order to connect with individuals you want to lead.10

Self-declaration will be ineffective without the ability to demonstrate values appropriately for the context, using social realism. Context itself, may also shift over time. Effective examples of social realism in action have been shown by Nelson Mandela of South Africa and Gerry Adams, the former leader of Sinn Féin.11 Both were seen as radical, revolutionary outsiders by their opposition, but transitioned their large followings to eventually hold power in legally legitimate parliaments. The ability to orchestrate such fundamental transitions, whilst showing enough consistency in their sense of self to not lose their support bases, is no small feat.

The art to such transitions, lies in conforming just enough to engage an ‘organisational gear’ to gain traction, without alienating your support base. Additionally, having a strong grasp of the context is important, but more so having enough of a grasp, to be able to shape it, by playing certain aspects to your advantage.12

Underpinning this social dexterity is a developed emotional intelligence, or ‘EQ’. The five areas of EQ are internal motivation, self-regulation, self-awareness, empathy and lastly social awareness. The benefits of internal motivation and self-regulation, (the ability to maintain composure under stressful or chaotic situations), are obvious for leadership. Nevertheless, self-awareness, empathy and social awareness are regularly overlooked, or deemed unessential ‘soft skills’, or even weaknesses.

Self-awareness in the context of EQ, is the ability to understand your own strengths, weaknesses and emotions, how they impact the way you feel and behave and importantly how they impact, or are perceived by others. Combined with social awareness (the ability to understand the emotions of others and pick up on social cues), and empathy (the ability to understand the emotions of others and see things from their perspective), it is evident that these are inherent to being an “authentic chameleon”, to avoid spinning your wheels as a leader when circumstances change.

A heightened sense of self-awareness correlates with the ability to openly recognise and discuss failings and weaknesses. Conversely, those with limited self-awareness are likely to interpret negative feedback or the need to improve as a threat or sign of failure.13 Not only do those responsible for promoting leaders tend to undervalue this skill, but it is often seen as weakness incompatible with leadership itself. Revealing weakness, strengthens human connections with followers and heightens authenticity; however, it is important to do so skillfully, to avoid over focus on a weakness becoming a defining characteristic, rather than a tolerable exception.14

The importance of EQ in leadership has been measured through a number of studies. In his research, Daniel Goleman discovered the following:

- When I analyzed all this data, I found dramatic results. To be sure intellect was a driver of outstanding performance. Cognitive skills such as big-picture thinking and long-term vision were particularly important. But, when I calculated the ration of technical skills, IQ, and emotional intelligence as ingredients of excellent performance, emotional intelligence proves to be twice as important as the others for jobs at all levels.”

- Moreover, my analysis showed that EI [emotional intelligence] played an increasingly important role at the highest levels of the company, where differences in technical skills are of negligible importance. In other words, the higher the rank of a person considered to be a star performer, the more emotional intelligence capabilities showed up as the reason for his or her effectiveness.

- When I compared star performers with average ones in senior leadership positions, nearly 90% of the differences in their profiles was attributable to emotional intelligence factors rather than cognitive abilities.15

Golemen is not alone in his study and assertion of the importance of EQ for successful and effective leadership. How then, does this correlate with the stereotype of leaders being authoritative, commanding and charismatic? According to Bill George, we should not be surprised that by looking at leaders as heroes and rockstars who run companies and that by focussing more on charisma, image and style over substance, that we do not get leaders with integrity. 2008 should serve as an awakening.16 Clearly there is a divergence between what has been evidentially shown to be vital in effective and successful leadership and the stereotypical perception of what it takes to be an effective and successful leader. Potential exists therefore, that companies are missing out on talented future leaders by misinterpreting their strengths as weaknesses.

Whilst data studies diverge, stereotypes often categorise emotional intelligence as having greater prevalence in the female population. So, are there lessons to be learned from how women approach leadership?

Female styles of leadership

The Harvard Business Review released an article ‘7 Leadership Lessons Men Can Learn From Women’ setting out behaviours more traditionally observed in women that are also shown to yield effective leadership results, which we can use to expand the analysis on female leadership styles.

1. Don’t lean in when you’ve got nothing to lean in about.

This refers to the advice levied at many women to “lean in” to qualities like assertiveness, boldness, or confidence.”17 At their worst, such traits can manifest as “self-promotion, taking credit for others’ achievements, and acting in aggressive ways.”18 Selection based on these qualities assumes a perfect correlation between confidence and competence, whilst overlooking other traits which can deliver broader benefits to teams.

2. Know your limitations.

This maxim posits that self-awareness is far more valuable than self-belief and in fact “awareness of your limitations (flaws and weaknesses) is incompatible with skyrocketing levels of self-belief”.19 Authors Chamorro-Premuzic and Gallop challenge the preconception that women lack confidence and suggest instead, that men display over-confidence. This is supported in various gender studies, including a study of forty-thousand fifteen-year-olds across nine countries. The test presented sixteen mathematical concepts and invited subject to indicate their knowledge from “never heard of it” to “know it well, understand the concept”. Some made up concepts were included in the list presented to the candidates. Male participants in all countries were far more likely to claim competence in the made-up concepts. Notably, the gap for North American students was lower, where both genders over-stated their proficiency in made up concepts.20

3. Motivate through transformation.

When measured against three leadership styles: transformational, transactional and laissez-faire, women are statistically more likely to demonstrate transformational qualities.21 The same study also discovered that transformational leadership styles contributed positively to the overall performance of subordinates.22

Hallmarks of transformational leadership include communicating values, purpose and importance of an organisation’s mission and qualities, that motivate respect or pride through association with that individual. Furthermore, they exhibit optimism and excitement about future goals, examine new perspectives for problem solving and focus on development and mentoring of followers whilst attending to their individual needs.23 Transformational leadership styles involve high levels of EQ and a time investment into winning hearts and minds. The result being higher levels of team engagement, performance and productivity.24

4. Put your people ahead of yourself.

Too much self-focus in terms of potential rewards leads to poorer results because there is less focus on developing team competencies. Whilst this statement is offered here as a female trait, it is also the bedrock of the predominantly male, British Army’s leadership philosophy, evidenced in the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst’s motto: “Serve to Lead”.

The ‘Serve to Lead’ philosophy declares that the men and women you are responsible for are your first priority.

“The principle of putting the needs of others before our own is enshrined in British Army leadership and it is the most powerful concept any leader can embody, and, critically, abide by. It forms the bedrock of trust. If those you lead know that you will do everything in your power to pursue and defend their interests, to put them before yourself, then their trust, loyalty and integrity are assured.”25

This echoes the importance of integrity, cited in earlier examples and the ability to connect with followers authentically. This embodies the important message, that leadership is not the same as authority. “Leadership is not imposed like authority. It is actually welcomed and wanted by the led.”26

5. Don’t command, empathise.

A great deal of leadership literature espouses the need to be selfish in order to be successful, such as Stephanie Burns’ article “6 Ways Being Selfish Can Make You Successful”.27 It would be easy to assume that empathy is at odds with selfishness. However, there is a key distinction in what these articles are telling us, firstly, the need to selfishly enforce boundaries to successfully navigate a corporate environment to avoid burnout, and secondly, how to be a true leader. Whilst both may be needed, they do not amount to the same thing.

Empathy, as seen with other EQ skills, is often undervalued but does serve a critical purpose in leadership. This does not mean collapsing in acquiescence to the wants of others, but showing “tough empathy”, empathising fiercely with followers, caring intensely about their people’s work, but giving them what they need to achieve their best, not necessarily what they want.28

6. Focus on elevating others.

Female leaders tend to invest more time and effort into developing others and a willingness to hire those better than themselves.29 This additional investment elevates the sense of value and belonging employees feel, translating into lower staff turnover and increased motivation. A more energised workforce will yield greater results, as they understand the collective benefit, rather than their work being credited to someone at the top.

7. Don’t say “you’re humbled”. Be humble.

Dovetailing again with EQ, humility works hand in glove with the ability to admit mistakes and learn from experience, with a willingness to improve.30 This reiterates the first point of the article regarding overconfidence. The author also suggests that the issue is not just a lack of humility in some men, but a selection bias, which also penalises the men who excel in this area.

The points raised in this article largely focus on qualitative and stylistic traits which are often overlooked in the search for leaders. Despite this, there is a wealth of quantitative evidence supporting the benefits of increasing the number of female leaders in corporations.

What are the other benefits to female leadership?

Increasing access to a broader talent pool and more diverse skills base, produces economic benefits for companies. On a macro basis, the Swiss Re Institute estimates that global gender parity would increase GDP by 26% and under these conditions, increase global insurance premiums by USD1.2 trillion by 2029.31

McKinsey research indicates that companies with greater diversity, especially more women, outperform on ROI by 20-25%.32 The Victoria Government in Australia identified a similar trend, that companies with at least 30% female leadership are 15% more profitable. In addition to this, they estimate that the Australian economy would grow by AUD 8 billion, if women transitioned from tertiary education into the workforce at the same rate as men.33

Viewing gender equality as a zero-sum game where men lose as women gain is overly simplistic and goes against much evidence to the contrary. The Australian research looks beyond pure economic benefits, noting several qualitative benefits including the fact that unequal societies are less cohesive. They have higher rates of anti-social behaviour and violence. Countries with greater gender equality are more connected. Their people are healthier and have better wellbeing.34

Men also suffer in the workforce from negative attitudes and stereotypes around parental care and flexible working. This is despite the fact that pre-pandemic, the numbers of men and women seeking flexible employment in the UK was almost equal.35 Reviewing the data from Aviva plc, a company that embraced equal parental leave, shows that stereotypes that men do not want career breaks to look after their children, as false.

Aviva’s policy of equal parental leave which started in 2017, offers men and women six months’ full basic pay. The purpose was to “remove barriers to career progression, challenge traditional gender roles and level the playing field for women and men at home and at work when a new child arrives.”36

Monitoring take up since its introduction at Aviva, it is clear that men have equal interest in childcare responsibilities when available:

- Equal parental leave has now been taken by over 2,500 people at Aviva, almost half of which (1,227) were men.

- 80% of men at the company have taken at least five months out of work when a new child arrives.

- The average length of paternity leave taken has increased by 3 weeks over the 4 years: in 2021 it was 24 weeks, compared to 21 weeks in 2018.

- The average length of maternity leave has slightly decreased over the last 4 years, from 45 weeks in 2018 to 43 weeks in 2021.37

Equal parental leave is often championed as one of the most impactful strategies companies can take to improve the gender balance of the workforce and leadership. Increasing the number of men and women in leadership positions taking parental leave, will force companies to adapt effectively to career breaks, making it easier in the future.

In light of the evidentiary benefits of gender parity in leadership, why is there still a deficit and what progress is being made to close the current gap?

Why don’t we have more female leaders?

Just under 20% of global board positions are held by women, but of the top jobs, this falls to 6.7% for board chairs, 5% for CEOs and 15.7% for CFOs.38 In the United Kingdom, female board representation has almost doubled since 2014, to 30.1% in 2021.39 Again, representation in the top jobs is much lower at 10.1%, 6.1% and 15.2% for board chairs, CEOs and CFOs respectively.40 Financial services is the top performing sector in the UK for female board positions with 33.3% overall.41

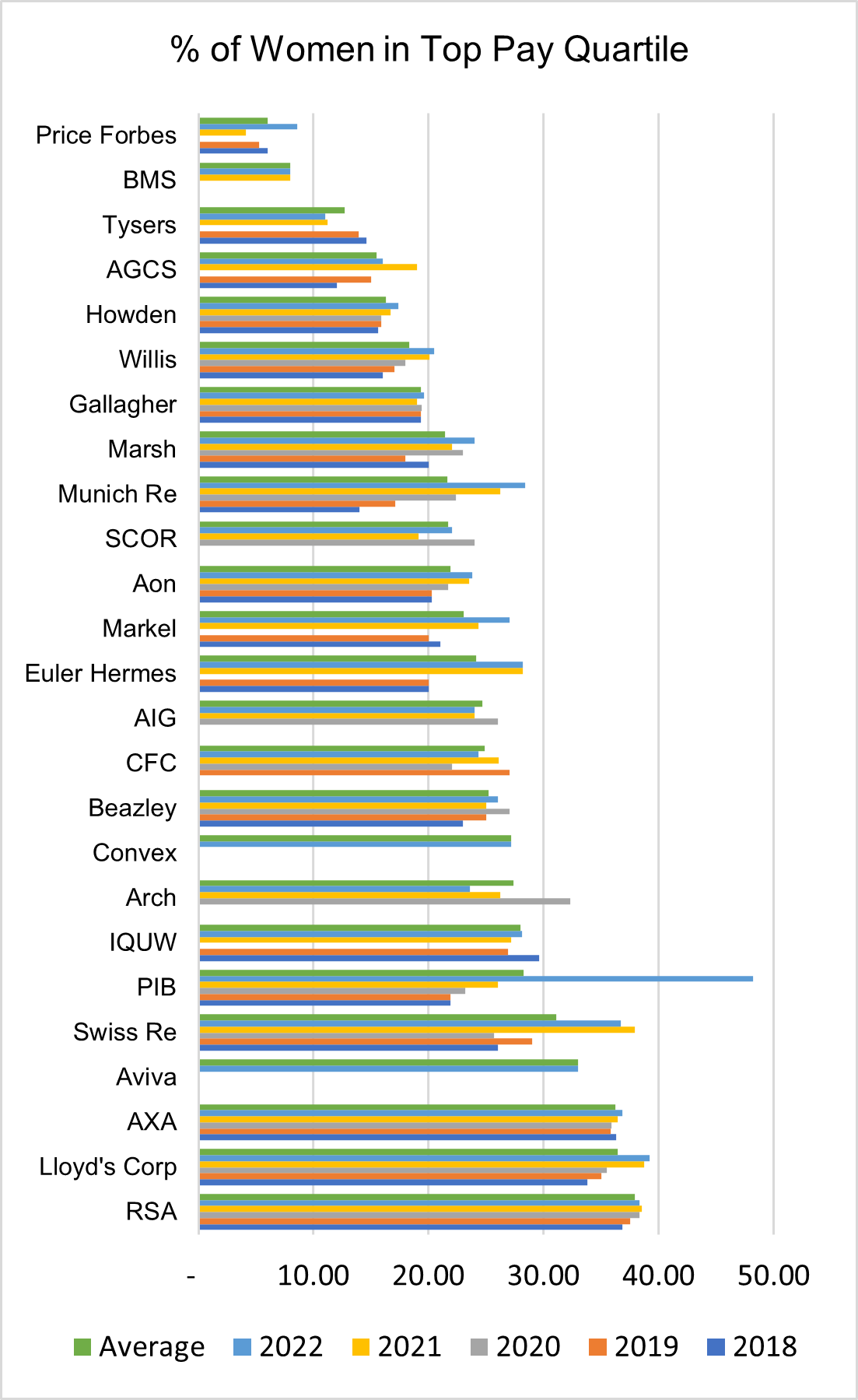

The number of board positions is only part of the story and UK gender pay gap reporting paints a different picture. Using the insurance industry as an example, the statistics show another trend: insurance companies noticeably outperform broking houses across a range of gender pay metrics. With the exception of PIB, who made a large jump in 2022, brokers are exclusively in the bottom 50% for the per centage of women in the top quartile of earners.42 Of those broking houses, performance directly corresponds to size, with the larger brokers having the highest per centage of women as top quartile earners and the smallest having the lowest.

Companies have become vocal about championing diversity and implementing new programmes and strategies to redress the balance, so why is there still such a gap? There are two elements in question in pay gap reporting, firstly the underlying number of women in senior roles and secondly, whether those in senior roles receive the same pay on average.

Looking purely at the numerical make up, there are many reasons contributing to the lack of female representation in leadership, here we will assess those related to skills development and recognition. As already noted by Bill George, practice and experience is essential for developing leadership skills. The Harvard Business Review article, ‘7 Leadership Lessons Men Can Learn From Women’, questions whether women really do lack confidence and perhaps this only appears to be the case when juxtaposed with male overconfidence. There is an alternative perspective, that women are generally less confident in the workplace, but that this is a learned response.

Confidence is built through experience of positive feedback, but asymmetrically eroded by the compounding effects of negative experience, due to negativity bias. Negativity bias is understood to be an evolutionary function whereby we recall negative experiences more strongly to increase chances of survival. As a result, we “attend to, learn from, and use negative information far more than positive information”43

There is a gender discrepancy in positive feedback loops across developmental stages and importantly within most corporate environments. One gender-based divergence is in the experience of trying to get ones point across in a group setting. Men interrupt women 33% more often, compared to when men are talking to other men.44 Additionally when receiving formal performance feedback, this tends to be more overtly negative, personality based and less constructive than that proffered to men.45

The difference in treatment is well illustrated by transgender individuals, who can directly compare their experiences living as both men and women. Ben Barres, a professor of neuroscience at Stanford University, who started his career as a woman, notes being taken more seriously since his transition46, being interrupted less47 and overheard comments such as “Ben Barres gave a great seminar today, but then his work is much better than his sisters.”48

These are just two small examples, but the result of such common negative experiences will dent the confidence of the majority. As Christine Lagarde and Angela Merkel have noted, this tends to manifest itself through over-preparing.49 The benefit of which is to minimise the scope for mistakes and increase overall competence. Nevertheless, high levels of competence are, conversely, not always beneficial for women.

One study gave information on how to survive a bushfire to one hundred and forty-three business students in approximately even male, female proportions and subsequently tested their knowledge, without revealing their results to the group. The highest performers, with no gender having superior results, were given “expert status”, again without this being disclosed to any of the participants.

One expert was included in each small group of students and the students asked to debate the topic and come up with their own estimate of the expert rankings. At the same time, the reviewing panel also judged the level of influence each member had over the group. The male experts were also judged to be the most expert by their peers and ranked as the most influential by the panel. The expert women; however, were judged by their peers to be less expert than other females and less influential by the observing panel. Overall, the men were more influential on the whole than the women.50

This is the competence paradox, evidenced in several studies, where experts are more likely to disagree and bring challenge in discussion, which is a well-received trait in men, but badly received for women. The result is women being incorrectly judged as less capable, than their less capable female peers.

Both male and female recipients of information shared by expert females, are less likely to trust that information51. The less expert females are more likely to agree with the group as they have less material to contribute, increasing their approval ratings and group perception.

What is the most effective method to overcome the issues identified? Thankfully, female participation and performance in the workforce has been well studied over several decades. Given the economic and equity benefits, most western governments and corporations have sought to increase female participation. Unfortunately however; some commonly employed efforts have had the opposite effect, so it is important to implement an evidence based strategy to address the issue.

How to increase female leadership

Corporate messaging around inclusion and diversity programmes focuses predominantly on alignment with corporate values and the processes in place

to address it. Focusing on the ‘what’ and the ‘how’, with little attention given to the ‘why’. Communicating the tangible quantitative and qualitative benefits that would be experienced by all, if greater progress was made towards gender parity is often missed, limiting the impact and acceptance of the strategies.

Often, available training, especially that provided on a mandatory basis can actually make the situation worse, awaken biases and alienate white men who feel unjustly accused or threatened about their future career prospects.52 Proven to be far more effective, are the approaches focusing on involving managers on a voluntary basis, to develop solutions and operational changes around mentorship, recruitment, working practices and overall transparency.53

Improving opportunities available for women in leadership roles is important, but to achieve the fullest economic benefits, it is important to focus beyond the traditional leadership skills, to the broader range of attributes proved to yield monetary results and providing the requisite opportunities to everyone to stretch and develop those skills.

How can we all become more effective leaders?

Internal motivation, self-regulation, self-awareness, empathy and lastly social awareness.

In the last twenty years of leadership literature, EQ has been shown to have a positive impact on business culture, as well as successful business outcomes. To become more effective as leaders, developing EQ remains foundational. An important facet of EQ leadership is the ability to tune into followers, understand their perspectives and communicate with them effectively. Developing EQ skills can be done but takes consistent effort. Being a ‘sensor’ collecting soft people data that allows you to rely on intuition and build authentic connections with followers - in short, the “ability to ask the right questions and listen – deeply – to the answers is not a ‘nice to have’ – it’s the only way to be successful”.54

- Listening.

In her book “The Listening Shift”, Janie Van Hool notes effective listening as one of the often overlooked ‘soft skills’, essential to leadership, but rarely forming part of any formal training. This is despite the recognised importance of being able to connect and accurately represent a following. In fact, there are

a myriad of emotional and psychological blockers to effective listening, compounded by the primary focus on presentation and communication skills.55 In fact ‘communication skills’ traditionally presents as the single sided communication of your own message to others, rather than how to be an effective participant in two-sided communication.

- Empathising.

A focus on listening in leadership ensures a greater ability to empathise. Helping followers feel understood and cared about is key to conversations about diversity, inclusivity and equality in organisations.

- Soliciting feedback.

Bill George notes the importance of maintaining a close network of individuals who know you and will provide unguarded feedback to keep you on track.56 This is critical to maintain the authenticity to be effective and to cater for formal feedback scenarios where individuals may guard their true views for personal reasons, such as fear of speaking out.

Feedback should not just come from external sources, but regular self-reflection and assessment of strengths, weaknesses and identification of what could be done better.

- Paying constant, ongoing attention to communication skills.

As Harvard Business School Professor Nitin Nohria said, “Communication is the real work of Leadership”. In particular, pay attention to emotional engagement – help people to understand their purpose and find meaning in the work they do in order to do their best work with their most committed energy.

Conclusion

In this paper, consideration has been given to the distinction between leadership and management, attention drawn to the merits of emotionally intelligent leadership and the potential toxicity of charisma and consideration given to the leadership landscape for women and implications for organisations.

In essence, leadership is about people and their right to choose whom they follow. As poet and philosopher Maya Angelou famously said, “People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

Often overlooked in the literature and training for how to become a better leader, but what should be the primary emphasis for us all, is an intrinsic and unwavering focus on those you wish to lead. Without this it may be possible to become an expert in your field, even a competent manager, but not, a truly effective leaer.

Becoming an effective leader is a constant exercise in self-reflection and evaluation in order to adapt, improve and do what is needed to stay relevant across changing social attitudes and communication styles.

Corporations can tap into broader talent pools and improve their performance by taking an evidence led approach, recruiting the skills and qualities that actually work, rather than those they are used to seeing.

1 “What Leaders Really Do”, John P. Kotter, Harvard Business Review, December 2002

2 “The Queen’s Commission, A Junior Officer’s Guide”

3“Adopting Mission Command: Developing Leaders for a Superior Command Culture”, Don Vandergriff, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019

4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xpe90T6_Dwk Bill George, 2011

5“The Allure of Toxic Leaders”, Jean Lipman-Blumen, Oxford University Press, 2004

6 “The Allure of Toxic Leaders”, Jean Lipman-Blumen, Oxford University Press, 2004

7 “Personal and Organizational Change Through Group Methods”, Edgar & Scein, 1965

8 “Why should Anyone Be Led By You?”, Gareth R. Jones & Rob Goffee, 2006

9 “The Trusted Advisor”, David Maister, Free Press Anniversary Edition Feb 2021

10 “Why should Anyone Be Led By You?”, Gareth R. Jones & Rob Goffee, 2006

11 “Why should Anyone Be Led By You?”, Gareth R. Jones & Rob Goffee, 2006

12 Why should Anyone Be Led By You?”, Gareth R. Jones & Rob Goffee, 2006

13 What Makes a Leader, IQ and technical skills are important, but emotional intelligence is the sine qua non of leadership. Daniel Goleman Harvard Business Review, January 2004

14 Why should anyone be led by you (section on taking personal risks)

15 What Makes a Leader, IQ and technical skills are important, but emotional intelligence is the sine qua non of leadership. Daniel Goleman Harvard Business Review, January 2004

16 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xpe90T6_Dwk Bill George, 2011

17 “7 Leadership Lessons Men Can Learn From Women”, Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic & Cindy Gallop, The Harvard Business Review, 2020

18 “7 Leadership Lessons Men Can Learn From Women”, Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic & Cindy Gallop, The Harvard Business Review, 2020

19 “7 Leadership Lessons Men Can Learn From Women”, Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic & Cindy Gallop, The Harvard Business Review, 2020

20 “Bullshitters. Who are they and what do we know about their lives?”, Jerrim, J.; Parker, P. and Shure, N. 2019

21 “Male vs Female Leaders: Analysis of Transformational, Transactional & Laissez-faire Women Leadership Styles”, D.A.C.Suranga Silva Senior Lecturer, University of Colombo B.A.K.M. Mendis Visiting Lecturer, Department of Economics, University of Colombo, 2017

22 “Male vs Female Leaders: Analysis of Transformational, Transactional & Laissez-faire Women Leadership Styles”, D.A.C.Suranga Silva Senior Lecturer, University of Colombo B.A.K.M. Mendis Visiting Lecturer, Department of Economics, University of Colombo, 2017

23 “Male vs Female Leaders: Analysis of Transformational, Transactional & Laissez-faire Women Leadership Styles”, D.A.C.Suranga Silva Senior Lecturer, University of Colombo B.A.K.M. Mendis Visiting Lecturer, Department of Economics, University of Colombo, 2017

24 “7 Leadership Lessons Men Can Learn From Women”, Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic & Cindy Gallop, The Harvard Business Review, 2020

25 “Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness”, Robert K. Greenleaf, New York: Paulist Press, 2002

26 Correlli Barnett’s Address to the Army Staff College, 1977

27 “6 Ways Being Selfish Can Make You Successful”, Forbes Women, Stephanie Burns March 12, 2020

28 “Why should Anyone Be Led By You?”, Gareth R. Jones & Rob Goffee, 2006

29 “7 Leadership Lessons Men Can Learn From Women”, Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic & Cindy Gallop, The Harvard Business Review, 2020

30 “7 Leadership Lessons Men Can Learn From Women”, Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic & Cindy Gallop, The Harvard Business Review, 2020

31 https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/topics-and-risk-dialogues/society-and-politics/gender-equality-matters-for-insurance.html#:~:text=There%20is%20strong%20evidence%20that,global%20insurance%20premiums%20by%202029.

32 https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/accelerating-diversity-in-insurance Violet Chung

33 https://www.vic.gov.au/benefits-gender-equality

34 https://www.vic.gov.au/benefits-gender-equality

35 “Language Matters”, LinkedIn

36 https://www.aviva.com/newsroom/news-releases/2022/06/takeup-of-equal-parental-leave-at-aviva-remains-high-after-four-years/

37 https://www.aviva.com/newsroom/news-releases/2022/06/takeup-of-equal-parental-leave-at-aviva-remains-high-after-four-years/

38 “Women in the boardroom: A global perspective”, Deloitte, Seventh edition

39 “Women in the boardroom: A global perspective”, Deloitte, Seventh edition

40 “Women in the boardroom: A global perspective”, Deloitte, Seventh edition

41 “Women in the boardroom: A global perspective”, Deloitte, Seventh edition

42 UK Government data on gender pay gap reporting for companies in the insurance sector with over 250 employees in the UK, excluding Life and Motor insurance companies https://gender-pay-gap.service.gov.uk/viewing/search-results?t=1&search=&orderBy=relevance

43 “Not all emotions are created equal: The negativity bias in social-emotional development”, Vaish, Grossmann, & Woodward, 2008

44 George Washington University Study, 2014

45 “How Gender Bias Corrupts Performance Reviews, and What to Do About It”, Harvard Business Review, Paola Cecchi-Dimeglio

46 “Why aren’t women advancing at work?”, Nordell

47 “The Hidden Brain”, Vedantam

48 “Does gender matter?”, Ben Barres

49“The Confidence Code”, Kay and Shipman

50 “When what you know if not enough”, Thomas-Hunt and Phillips

51 “The risks and rewards of speaking up” Burris

52 “Race in America: Diversity training”, Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev explain why diversity trainings does not work, The Economist, May 21st 2021

53 “Race in America: Diversity training”, Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev explain why diversity trainings does not work, The Economist, May 21st 2021

54 “The Listening Shift: Transform your organization by listening to your people and helping your people listen to you”, Janie Van Hool, Practical Inspiration Publishing, 2021

55 “The Listening Shift: Transform your organization by listening to your people and helping your people listen to you”, Janie Van Hool, Practical Inspiration Publishing, 2021

56 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xpe90T6_Dwk Bill George, 2011