Mental Health Disorders

Insurability (Life & Health)

by Nicolas Denys, Head Of Employee Benefits, Group Risk Management, AXA Group

1. Mental Health…a growing concern for the society

Around 970 million people (13% of the world population) suffered from mental disorders in 2019 (The Lancet, 2020). Mental health conditions are one of the most common factors behind suicide (46% according to National Alliance of Mental Health), but the impact of mental health is not limited to the risk of death.

According to the World Health Organization, mental health is “a state of wellbeing in which individuals can realise their own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and are able to contribute to their community”.

Currently, there is no widely acknowledged clinical definition of mental health problems. However, Mental Health disorder can be diagnosed according to standardised criteria. One common reference used to define mental disorders is the 10th edition of International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10).

Mental health conditions’ refer to both short-term mental health problems and long-term mental disorders. The most common mental health conditions are anxiety and depressive disorders. Mental health conditions are the main cause of disability and early retirement in many countries and a major burden to economies. In the workplace, up to 50% of chronic sick leave is taken due to depression or anxiety.The Covid-19 pandemic has been a catalyst and made it even more so visible that we face an upward trend, both in terms of the number of people affected and the related costs.

1.2. What is the trend of mental health disorder?

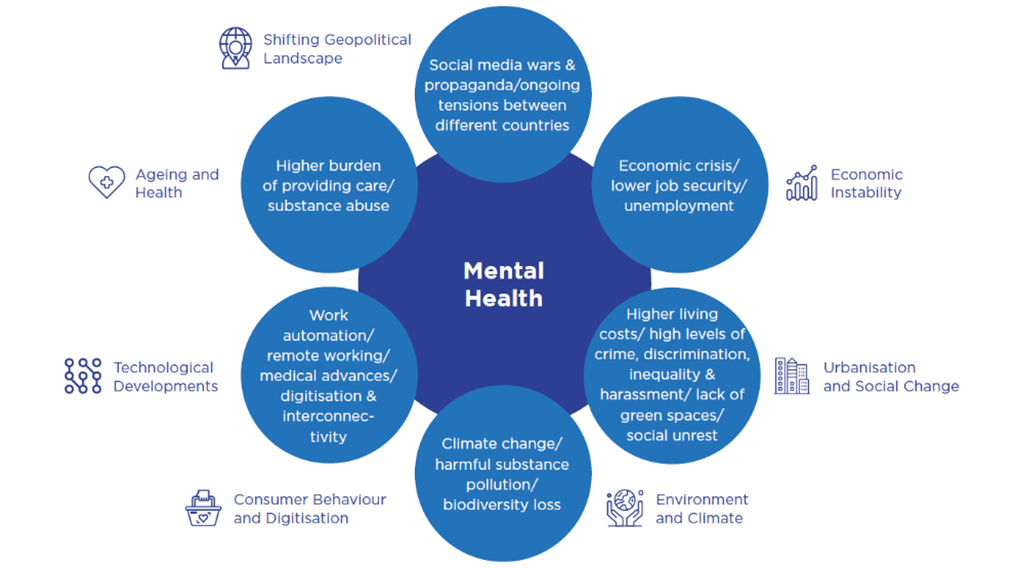

People’s mental health is influenced by a broad range of risk factors and determinants, an often-complex mix of biological, psychological, and social factors. It is difficult to quantify to what extent each factor contributes to the incidence of mental health conditions. Some of the major illnesses are depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, bipolar mood disorder, personality disorders, and eating disorders.

Mental health related trends and figures are on the rise. We can, therefore, expect an increase in mental health-related risks both in the insurance industry and in society as a whole. The landscape of issues inherent to mental health disorder increase is wide. The graph hereafter illustrates some of them.

For example, women are more likely to be diagnosed with depression, anxiety, and related somatic complaints than men. 4.4% of the worldwide female population) suffered from depression, while the average prevalence among males was only 2.8%, with around 109 million affected (The Lancet, 2020; WHO,2020).

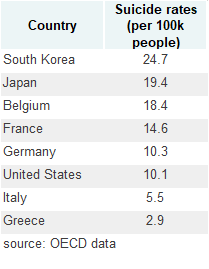

Mental health disorders statistics are also different per geographic zones explained either by socio-demographic information, economic situation, and cultural behaviour. It is not easy to get comparable data as data are often biased by cultural acceptance and stigma of mental disorders. In “collective” societies (Asia and others) individuals with mental disorders have been massively stigmatizes making it difficult to seek appropriate care and leading to false low figures on incidence and prevalence of mental disorders. However, the suicide rate illustrates these geographic differences. The suicide rate in South Korea (the highest in OECD) is more than eight times the suicide rate in Greece (the lowest).

1.3. What are people needs and public response?

People will expect public and private sectors to support them before, during and after mental health conditions.

Mental healthcare encompasses services devoted to treating mental health conditions. Mental health prevention, or ‘public mental health’, usually refers to efforts to stop mental health problems before they arise. Mental health treatments provide care adapted to the type of mental health condition and the individual’s situation. Some may have recurring recovery and relapse phases. Recovery means gaining and retaining hope.

In response to increasing awareness and demand for mental healthcare treatments and services, some public health systems have sought to close the gap in coverage of mental health conditions. However, this coverage faces limitations and differs from one country to another. In many countries mental healthcare costs are still largely out-of-pocket.

Taking stock of the lockdowns’ negative impacts on mental health, governments have initiated several programs to address this issue (OECD/European Commission, 2020). For example, in Germany, a broad alliance of several ministries and organisations came up with an initiative to focus on mental health in response to the pandemic. Canada provided a mental health helpline offering e-mental health services and counselling for children.

It is worth notice that we observe a recent rise in telemedicine treatment of mental health conditions. Compared with conventional treatment methods, telemedicine benefits from being more convenient, more accessible, and cheaper for some patients.

2. Mental Health conditions: Uninsurable risk?

The question of the impact of psychosocial risks on people's incapacity to work is as thorny as that of the impact of climatic risks on material and physical damage, in the sense that it regularly animates debates with a certain difficulty in acting on the causes of the problem and limiting its evolution over time.

Common mental disorders, like depression or burnout, are among the most frequent reasons for long-term absence from work. Over the past decade, regarding working incapacity, there has been a shift in claims related to physical health (e.g. cancer and cardiovascular risks) to mental health. The rise in mental health risks worldwide is expected to lead to an increase in the number and complexity of claims in Health & Protection insurance, which raise the question of future assurability or affordability for the clients.

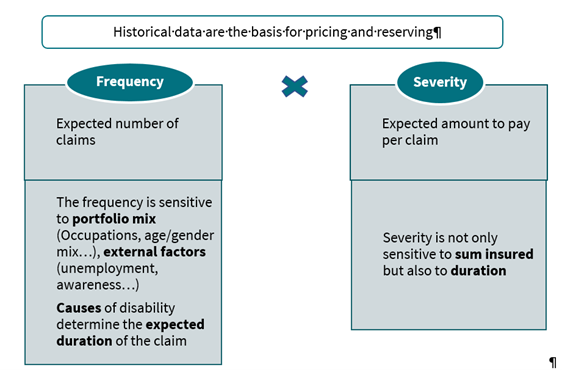

Traditional approach to know if a risk can be insured is to ask actuaries if we can price for it. We can give a price for a defined cover if are able to predict the claims frequency and severity. In the case of mental health, I already highlighted that disorder may be influenced by multiple factors: i) economic environment (unemployment rate, economic forecast….), ii) the availability and efficiency of treatment and therapies, whether medical or using different kind of support iii) societal perception (a greater acceptability of the status can increase the frequency of declaration, benefits awareness either public or private can also reinforce identification of “claimants”).

In this paper, I will explore the ability of insurers to offer disability and sick leave coverage, which is an even more difficult issue than offering death coverage.

What are the challenges & risk mitigation measures?

Challenges, specific to mental health conditions coverage can be split in four main areas: i) data/pricing/risk modelling, ii) underwriting, iii) claims management, iv) regulatory change. In the following I will summarize it with classical insurers answers to mitigate the different risks.

The panel of risk mitigants is limited by broader consideration as we talk about a very sensitive topic. Answers to mitigate the risk for the insurers will not be possible when it does not respect the following prerequisites: i) Regulators’ expectations (Customer fairness, equitable and ethical practices), ii) Clients’ minimum expectations (Non-discrimination & transparency in risk assessment criteria, clear and efficient claims management).

2.1. Data, Pricing and product design

The challenges in data quality and future trends’ modelling are high.

As for any risk, high quality and granularity of data is essential to design and price the products. The usual modelling on disability is composed of two variables: frequency (~incidence) and severity (~recovery) of the risks.

So far, the causes of claims have never been used for pricing and reserving, meaning frequency and severity are analyzed independently of the causes. Historic trends on the prevalence of different types of mental health conditions are often unavailable or unreliable.

The existing differences between countries’ disability covers limit insurers’ ability to use aggregated data. The differences can come from the definition of the disability and the claims process assessment, the elimination and waiting periods, the limit duration of benefits, etc.

Modelling future trends in incidence and recovery rates with significant uncertainty on how these may evolve also proves complicated. This is, to a large extent, due to lack of historic data, the multi-risk drivers that can influence future trends’ development, and the specificities of every generation.

Most of the time, the recovery rate is not analyzed in a dynamic way although research has shown that it is a dynamic process, with individuals moving in and out of states of disability. Only the ratio between recoveries and current claims are monitored. Recovery rate tables are most of the time calculated at country level on a population which may be not the insured population.

When pricing is uncertain and the product is of long-term nature, mitigations are in general the following: conservative pricing, monitoring of the performance, cross-subsidization between the different generations with some regulation allowing for global profit-sharing mechanism which limit the annual maximum margin of insurers and help to reserve for future risk deviation. When it is possible (not always the case when private and public cover are closely connected), the insurers can limit the benefit payment maximum period (in Belgium for example, insurers limit the period of benefits to three years for mental health conditions).

In an attempt to reduce the antiselection risk and the impact of short-term sick leaves due to mental health, insurers could introduce a waiting period in their policy wording (the period from the policy inception after which a claim can be made) and/or a deferred/elimination period (the period between the start of disability and when the first annuity benefit is paid).

Gender is one key criteria which influences the incident rate but is not the only one. Insurers will need to pay attention to the age. While disability risk has been in the past significantly higher for older people and blue collar, the rise in mental health disorders could change the paradigm. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (2021), it is estimated that more than 13% of adolescents aged 10-19 live with a diagnosed mental condition (as defined by ICD-10). In addition, there is increasing attention on how excessive digital media use impacts mental health. Girls who used social media for at least two to three hours per day at the beginning of the study – when they were about 13 years old - and then greatly increased their use over time, were at a higher clinical risk for suicide as emerging adults (Brigham Young University, 2021).

We observe several statistics in our AXA portfolio that confirm that the insured population behaves similarly to the general population. The incidence rates for women are higher than for men, with differences that can vary from one country to another (from +20% to +100%). The burden of mental health disorder claims is significant (between 30% to 50% on average for all age groups) and higher in the age group (20-35y) of young insured persons.

While some effects related to mental health disorders are observed in insurance portfolios similar to observations on the general population, it remains difficult to extrapolate the latter for three main reasons: the specific nature of the guarantees covered, the profile of individuals and also the effects of medical underwriting.

2.2. Underwriting

Due to the complexity and uncertainty around what causes certain mental health conditions, the traditional underwriting approach may either under or overestimate an individual’s risk of future mental health claims. Family history may be unavailable (due to data privacy regulations) or unreliable. The same disease may have different impact on two persons. One customer could be diagnosed with severe depression and continue working effectively while another customer in similar circumstances may be not able to function at work and claim benefits.

Using targeted application questions at the underwriting stage might help to ensure a more accurate risk assessment, considering these co-morbidities. This could possibly serve as the foundation for more selective approach to mental health related disorders without compromising the quality of risk assessment using substandard and exclusion-based underwriting. However, it seems like experience with targeted questions across the industry is scarce as pushback from distribution channels have previously been a major concern.

Genetic predisposition and/or certain stressors may pre-dispose individuals to develop mental disorders. Various factors can trigger a higher risk: loneliness, family conflict, low income, discrimination, exposure to war/disaster, social inequalities, substance abuse…All factors could strengthen the underwriting rules. However, a careful use of them needs to be done as it raises fundamental ethical questions on top of limits imposed by different regulations.

If individual underwriting has some limits to estimate the individual’s risk of future claims, the management of antiselection is still possible with a focus on high sum insured. Overinsurance needs to be avoided as it has been shown that it encourages abuse and early claiming. Financial underwriting is needed when benefits exceed a certain level. This threshold varies from market to market.

When products are designed to cover sick leave or occupation-disability, one of the key criteria is the claims definition.

In the insurance contract, disability is generally defined as functional impairment caused by a medical illness or injury: the illness or injury itself is necessary but not sufficient to qualify for the benefits – an impaired individual is not necessarily disabled. The functional impairment, which is the gap between what a person can do and what the person needs or wants to do in a professional context, also needs to be clearly established in order to constitute a disability claim. Therefore, assessing a disability insurance claim involves assessing if and how much the medical impairment prevents the person from working and their likelihood of returning to work in the future.

Definitions of the threshold of functional impairment to qualify for a disability claim varies from market to market and can range from “unable to work in own occupation” to “unable to work any occupation” or “unlikely to work in any occupation reasonably suited or qualified considering social and economic status”. The assessment of a disability claim requires three major components:

- Functional requirement: the exact tasks required to be performed in the last occupation prior to disability

- Capacity impact: impact, caused by illness/injury/condition and its treatment, that would not allow the insured to fulfil the functional requirements

- Residual capacity: based on the assessment of the residual capacity and prognosis, consider the barriers of social integration and assess the likelihood of future employment on his/her own or any occupation depending on definition of the policy contract. The residual capacity defines the degree of disability, expressed as a percentage, where: degree of disability = 1 – residual capacity.

By their nature, mental health claims are difficult to manage. First because behind “mental health” stands a large variety of diseases and specific stakes (difficulty in diagnosis, multiple issues). Claims management is also more complex as it requires specific examination to assess if the case is covered by the policies. When the claims referral is not aligned with public system decision, the insurer will frequently ask for Independent Medical Examinations (IMEs).

After the confirmation of the claim, the question of its seriousness quickly arises and is necessary to estimate the total cost. My company identified here many traps we should avoid when defining the risk cover and writing the Terms & Conditions. Mental disorders have a wide spectrum of severity. They may be persistent, recurring, relapsing, and remitting or can occur as a single episode. Severe forms which might need hospitalisation make the individual dysfunctional and substantially interfere with or limit their major life activities. The first five years from the date of diagnosis are usually crucial with respect to the long prognosis.

Local regulators also ensure market good practices. Mental health and insurance coverage of mental health conditions is an area of concern for regulators in many countries. As an example, UK Association of British Insurers (ABI), are issuing guidance to insurers on how to interact with customers suffering from mental health conditions, including underwriting and claims practices. On top of that, strengthening claims handlers’ knowledge of mental health would improve how they manage these claims.

The difficulty of correctly measuring the working capacity of individuals with mental health conditions is a real challenge. In addition, medical professionals, despite having limited to no training on occupational functional assessment, are often called upon as experts in claims settlement.

At least, mental health knowledge should help insurance industry not repeating past mistakes. Paid sick leave schemes are open to abuse, especially if the benefits levels appear generous and the state oriented to protect citizens first.

There is one concrete example in Australia where many insurers made significant losses on disability risk in 2012-2014.

What we learn from the Australian example, is multiple: i) ensure that benefits are not too generous and do not exceed the income of the insured at the time of a claim, ii) refuse to offer insurance policies with unclear Terms & Conditions allowing very late claims notification and difficult claims assessment, and iii) ensuring that effective controls are in place to manage the risks associated with long benefit periods.

Some remediations have been taken to clarify the benefits definition. However, I recently noted that i) an analysis from KPMG revealed that the number of claim benefits paid for mental health conditions has doubled between 2013 and 2020, and ii) the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (CCA) and the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) provide a number of obligations on businesses to protect vulnerable consumers. This situtation led the Australian Actuaries Institute in September 2020 to make “recommendations for broad changes to Australia’s retail disability income insurance market to reset sustainability for a sector under threat”.

In conclusion, the mental health conditions can be covered by sick leave and disability insurance but it should be emphasized that mental health-related uncertainties pose transversal challenges to the insurance industry such as concerns related to discrimination, anti-selection, and complexity of diagnosis in the underwriting and risk assessment phases, increased incidence, unreliable data, difficulties in medical classifications for claims management, and reporting complexity due to social stigma. In addition, the assessment of mental health-related claims is less standardised, thus prone to arbitrary and unexpected outcomes.

3. What insurance leaders need to strengthen?

3.1. Why the private sector needs to provide solutions?

Insurers need to accept the challenge of mental health and play their part in meeting society's evolving protection needs. Burden-sharing between the public and private sector is essential to promote better mental health. Insurers have an important role to play providing expertise and using different levers to improve prevention and mitigation of mental health risks, to ultimately serve societies’ evolving needs.

In time of crisis, many employees fear dismissal when reporting sick in the absence of cover. Without or with limited health coverage, the choice for an employee between deteriorating health and risking impoverishment of themselves and their families is a difficult dilemma. Employee benefits solutions are costly for employers but help them to better manage their workforce, so the cover is more than a benefit for employees on top of their salary. With good cooperation with an insurer, it can become a powerful tool to maintain healthy workforce.

Furthermore, with individual contracts, insurers can provide continuous support and reassessments for mental health conditions throughout the policy’s life.

In some cases, insurers can not escape from their contribution to the solidarity when regulators formally ask them to cover additional risk. As examples i) starting 2022, Social Security in France is covering psychologist sessions for all people aged three and above when prescribed by their general practitioner, ii) the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India has asked Health Insurance providers to include mental illnesses under the umbrella of Health insurance coverage.

Cooperation between public authorities & private sector should contribute to limit the rise of the risk before one raises the question of affordability. For the insurance industry, opportunities exist to develop sustainable products and services that will contribute to its purpose of serving the vulnerable and building more resilient societies. I acknowledge that mental disorders such as schizophrenia, major depression, borderline syndromes etc. which have a strong genetic component cannot be overcome easily, if at all, but this should not limit the effort needed to address mental health problems.

Beyond, classical risk mitigations described in the previous section, I will present additional mitigation measures which must take the form of both protection and prevention. Insurers should take into consideration the different avenues through which mental wellbeing can be strengthened and mental health conditions managed.

3.2. Return To Work “RtW” program

While mental health conditions can make employees unable to work, poor working conditions can further exacerbate the situation.

Mental health conditions often have a poor medical prognosis resulting in low recovery rates as the patient’s symptoms become chronic.

Returning to long working hours and a highly competitive labour force might be disincentives for individuals to go back to work which increases risk of malingering (Waddell, Burton, & Kendall, 2008). Some predictors for nonreturn to work are severity of mental disease, short conscientiousness, advanced age, comorbidities, and other mental health disorders (Swiss Re, 2020).

A joint effort between the insurance companies, employers and third-party service providers should develop mechanisms that support an early return to work, thus helping to avoid the condition becoming chronic. There needs to be a facility built into disability covers that would allow an individual to have access to rehabilitation programs promoting early reintegration in their former role or move to a new environment or role.

Many Insurers have already included RtW program in their offer, but tackling mostly high claims cost and long-term disability. Most of the time, the support comes too late to be effective.

With additional data and, in some markets, access to all sick leave data, it becomes possible to identify at-risk individuals (cumulative sick leave) earlier, and especially before the effect of insurance coverage. For large companies, it is interesting to compare whether their sick leave statistics are better or worse than those of companies in the same industry and to analyze whether the work environment is a cause.

Providing support for RtW benefits the insurance company with a claim reduction but it also benefits people. Feeling productive positively impacts an individual’s mental wellbeing and the normality of work potentially helps the insured recover from mental health conditions. Thus, encouraging to resume familiar habits can decrease the symptoms associated with mental health conditions and build up an individual’s confidence. In due course, RtW programs convey messages of resilience, recovery, and the health benefits of work, all part of economic and social justice. Research shows that keeping people from returning to work and not facilitating RtW - when it is safe to do so - can be harmful to health, social, and economic status (Brijnath, et al., 2014).

Voluntary agreement for participation to RtW program is often a limit of the program effectiveness. How to increase the usage of this service remains a challenge. Communication and care management is part of the answer I cover in the next section.

3.3. Health Ecosystem (Services & prevention)

Prevention in mental health undertakes to reduce the incidence, prevalence, and recurrence of mental health disorders and their associated disabilities.

By offering intervention services in the early stages of mental health conditions, the risk of more disruptive health conditions for the patient and higher-cost interventions can be alleviated.

Collective efforts are required to put in place preventive actions that can minimise the rising numbers of claims on the industry and improve insureds overall wellbeing. The goal is clearly to moving from medically treating the problem to preventing it. Thanks to their knowledge, insurers could envisage providing education to vulnerable populations on how to take better care of their mental health.

How can these services be offered to customers?

Insurers have understood that to deliver prevention and provide health and welfare services, it is necessary to create the right ecosystem. For example, AXA has developed an ecosystem in several Asian countries under the name Emma. “Emma” is an all-in-one digital platform enabling the client to manage its contracts (benefits view, policy update, claims process…), but also offering personalized access to a comprehensive suite of programs and services that cover physical health, mental wellness and chronic disease management. To help in their well-being, customers can access health articles and virtual exercise classes in the comfort of their homes. There is even a point rewards feature that can be exchanged for prizes. Emma includes a chat box, and the desire to create a very personalized link with the insured to foster habits and thus improve the use of services.

In terms of wellness reward, other experiences can be mentioned.

To promote healthy lifestyle habits, some insurers have provided an incentive to their policyholders by offering insurance plans with financial rewards. One of the most well-known comprehensive incentive-based wellness program is “Discovery Vitality”. It has been designed around evidence-based interventions and behavioural economics to improve health outcomes. Discovery Vitality was first launched in the South Africa market in 1997. Between 2010 and 2015, several insurers (Generali, Prudential, etc.), in partnership with Discovery or other tech-compagnies, took advantage of the spread of connected watches to launch programs to promote good behavior by their policyholders. The usage of data is still limited, partly due to regulation constraint and consequently investment have been reduced on this matter. However, if regulation changes and people become more ready to share their health data, the potential will be huge. The adoption of technology may be long if we look backward to the example of mobile phone & internet…but when it accelerates it can drastically change our daily life. The same may happen in the way to use personal big data in healthcare management.

What complementary cooperations are possible within the framework of Employee Benefits contracts?

Insurers should encourage employers to address mental wellbeing in their workplace and lending them support by establishing and providing the leading warning signs.

As P&C insurers are proactive in helping industrial clients to review their fire risk safety systems, life insurers can support human resources department to build training program including a large place to develop positive managers behaviours. The resilience is a skill which reduce the burn-out risks (Cooke & all 2013).

Focused initiatives may be defined for more vulnerable population such as the women, the elderly and frontline workers. As an example, some service companies specializing in the management of post-maternity stress, provide individualized support to help mothers returning from maternity leave.

As mental health is a critical part of an individual's overall health and well-being, solutions must be incorporated into the care management program. These must make it possible to meet the cost of medical treatment in mental health, which still too often constitutes an obstacle to treatment at an early stage.

Gravie is an example of insurtech company working with brokers and insurers to provide care management solution including mental health needs. By utilizing preventive care like therapy, individuals are less likely to postpone care until a crisis happens and they need to be rushed to the emergency room. This adds up to a better experience for the individual, and significant cost savings for the employer and insurer — it’s the win-win formula.

Structurally there may be a shortage of resources: lack of trained professionals, a higher incidence of mental health conditions among frontline workers, an increase in service prices and waiting periods. Such an imbalance in demand and supply could lead to the development of a “provider market”. Providing affordable broad-coverage healthcare products might mitigate the risk of a provider market and meet the demands of multiple populations.

To cover mental health conditions’ treatment gaps, insurers could consider developing inclusive protection offers that cover the protection gaps of traditional insurance. These offers could therefore resolve both the mental health protection gap and the financial exclusion vulnerable populations face.

3.4. Additional contribution from public authorities

As previously mentioned, the quality of pricing relies on data. For mental health and more globally health, regulators are generally inclined to strengthen the framework for the protection of individual data, thereby limiting the possibility of collecting and storing aggregated data. In many cases, the information exists at the level of public authorities but is not sufficiently exploited. In France, an initiative led by C. Villani (2018) for the government, making public health database “système national des données de santé (SNDS)” available to incentivize AI initiatives, considering artificial intelligence could improve access to care, as well as the quality and safety of treatment.

By giving flexibility to insurers but also to the medical profession in the use of data and therefore knowledge of the risk, the public authorities will help to contain its evolution.

Uncertainties related to mental health pose cross-cutting challenges to the insurance industry, such as concerns about discrimination, anti-selection, and complexity of diagnosis in the underwriting and claims evaluation phases. The increased incidence, unreliable and incomplete data, and difficulties in medical classifications for claims management create problems in accurately measuring and forecasting the cost of claims.

However, with a comprehensive approach it is still possible for insurers to manage such risk and cover it in the sick leave and disability policies. The problem is the increase in mental health disorders and their consequences. A trend has already been observed and will likely be reinforced in a crisis environment if we do not work effectively to stem the problem. To address this problem at its source, cooperation between public authorities, insurers and the private sector is essential.

By giving flexibility to insurers but also to the medical profession in the use of data and thus knowledge of the risk, public authorities can help contain its evolution. Employers and insurers must cooperate to improve working conditions, promote wellness and good habits, provide a set of services generally integrated into the health ecosystem and including the prevention and management of care related to mental health disorders. The solutions already exist but are not at the level needed for widespread and effective use. Beyond the technical solutions, the willingness to address the mental health issue, the investment and communication efforts will be decisive. To be more effective in controlling this risk, it is useful to be as proactive as possible and to provide upstream support to vulnerable people. Mental disorders such as schizophrenia, major depression, borderline syndromes etc. which have a strong genetic component cannot be overcome easily, if at all, but this should not hinder efforts to treat other cases.

References

AXA Foreseight (2020). The future of Mind Health and Well-Being. Paris

Brigham Young University. (2021, February 03). 10-year BYU Study Shows Elevated Suicide Risk from Excess Social Media Time for Young Teen Girls. Retrieved from https://news.byu.edu/intellect/10-year-byu-study-shows-elevated-suicide-risk-from-excess-social-media-time-for-young-teen-girls

Brijnath, B., Mazza, D., Singh, N., Kosny, A., Ruseckaite, R., & Collie, A. (2014, March). Mental Health Claims. Management and Return to Work: Qualitative Insights from Melbourne, Australia. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation.

Cooke GP, Doust JA, Steele MC (2013). A survey of resilience, burnout, and tolerance of uncertainty in Australian general practice registrars. BMC Medical Education.

OECD/European Comission. (2020). Health at a Glance: Europe 2020. Paris. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-europe-2020_82129230-en

Swiss Re. (2020). Changing minds: How can insurers make a difference on the mental health journey? Zurich: Swiss Re Institute.

The Lancet. (2020). Global Health Metrics: Depressive disorders - Level 3 cause. The Lancet. Retrieved from https://www.thelancet.com/pb-assets/Lancet/gbd/summaries/diseases/depressive-disorders.pdf

The Lancet. (2020). Global Health Metrics: Mental Disorders - Level 2 Cause. The Lancet.

Villani (2018) Retrieved from https://www.vidal.fr/actualites/22654-intelligence-artificielle-en-sante-analyses-et-recommandations-du-rapport-villani.html

Waddell, G., Burton, K. A., & Kendall, N. A. (2008). Vocational Rehabilitation: What Works, for Whom, and When?