And They Say Actuaries Look Through a Rearview Mirror…

IIS Executive Insights Life & Health Expert: Ronald Klein, Executive Director, BILTIR

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines an actuary as, “A person who calculates insurance and annuity premiums, reserves, and dividends.”i The U.S. Society of Actuaries’ (SOA) and Casualty Society of Actuaries’ (CAS) joint website, “Be an Actuary,” expands on this definition, stating that actuaries are experts in:ii

- Evaluating the likelihood of future events—using numbers, not crystal balls

- Designing creative ways to reduce the likelihood of undesirable events

- Decreasing the impact of undesirable events that do occur

Actuaries typically rely on the vast amount of data available about insurance events—such as mortality, morbidity, and catastrophes—to make future projections. While considering views of economists, medical doctors, scientists, executives, politicians, and other professionals when constructing their models, actuaries typically prefer a long history of reliable data versus an expert’s opinion. For that reason, actuaries are often personified as professionals who look through a rearview mirror. One joke (of many) about actuaries is that when they are in the passenger seat of a car, they will tell the blind driver how to drive by looking in the rearview mirror.

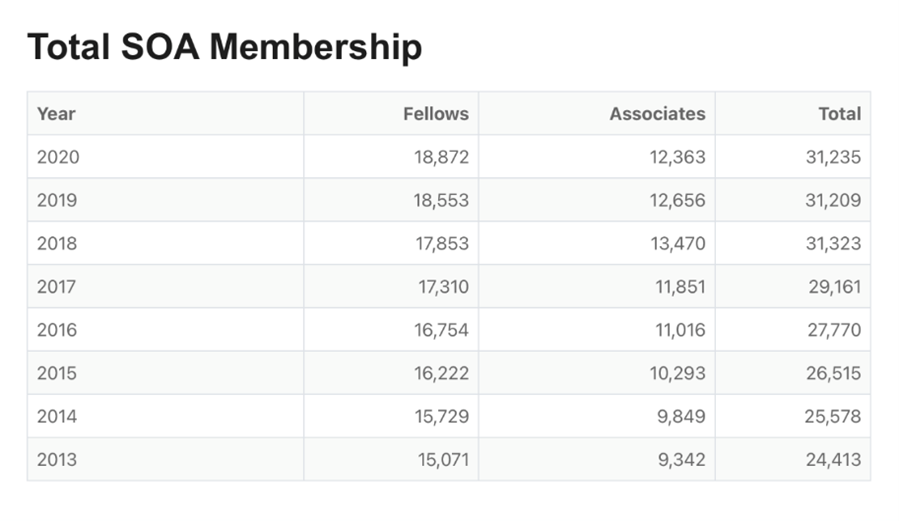

Still, qualified actuaries are part of an exclusive club. According to the SOA, there were nearly 19,000 fellows and more than 12,000 associates at the end of 2020 (see Figure 1).iii

Figure 1

The total number of qualified actuaries worldwide is estimated to be only 70,000.iv Considering that the SOA is not the only association in the United States with qualified actuaries—the American Academy of Actuaries, American Society of Enrolled Actuaries, Casualty Actuarial Society, and the Conference of Consulting Actuaries are the other four—it may be safe to assume that approximately half of all worldwide actuaries are members of a U.S. actuarial association. Compare this with the estimated 5 million accountants and 5 million lawyers worldwide, and one can easily see why the profession is highly regarded and largely anonymous at the same time.

Other Rearview Mirror Gazers

The rearview memes about actuaries may be warranted to some extent, but it is not the only profession that looks over its shoulder to predict the future. Since 2004, the consulting firm McKinsey & Company has been conducting an annual survey—the McKinsey Global Surveys.

The company reports in the survey introduction that it polls “…thousands of executives and managers to generate new and distinctive insights on today’s critical business topics.”v] The past few surveys reveal a response rate of approximately 1,000 executives each year.

The survey covers many topics that McKinsey expertly analyzes. One of the more interesting reports is about economic outlooks and the most influential risks that will face the world in the next 12 months. Respondents are able to choose from a list of 15 predetermined risks.

In September 2019, the top five risks identified by this elite group were trade conflicts (65 percent), geopolitical instability (54 percent), changes in trade policy (35 percent), social unrest (20 percent) and transitions of political leadership (17 percent). At that time, Donald Trump was president of the United States and several things were happening:

- The North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement was under attack and ultimately disbanded early in 2020 (trade conflicts, changes in trade policy).

- It looked like Trump would lose the 2020 election (transitions of political leadership).

- There was an uprising of “populist” world leaders (social unrest).

- The U.S. seemed to be withdrawing from alliances with Europe while having trade wars with China (geopolitical instability).

On the horizon, just a few months into the future, loomed a pandemic that caused death, disability, large-scale unemployment, and supply-chain shocks. The McKinsey respondents did not mention the COVID-19 pandemic in the top five risks likely to have a global impact in the next 12 months. But in March 2020, just six months later, the results were dramatically different.

At that time, 86 percent of respondents identified the COVID pandemic as a major economic risk for the next 12 months. Financial market stability also snuck into the top five with 22 percent. This new risk topped the charts as news of the virus hit the media. Fear for financial markets was running rampant, even though the stock market performed quite well throughout the pandemic.

The most recent study lists geopolitical instability and/or conflicts as the most reported risk due to the invasion of Ukraine by Russia. It also identifies inflation, volatile energy prices, supply chain, and rising interest rates as major risks—all of which have already begun to emerge, and some, many have said, should have been foreseen.

Some may say that these executives are predicting emerging risks in the next 12 months by looking in the rearview mirror.

A Risky World

So, what should we make of all this, and how does it relate to life insurance?

What is most striking about the McKinsey Economic Outlook Survey results during the past few years is not that the 1,000-plus respondents keep changing their views every few months as new risks emerge, but that there are so many new risks emerging. Unlike the World Economic Forum annual survey of economists, politicians, and other influencers where climate-related events have topped the list for the past decade, McKinsey’s business leaders cite an ever-changing list of risks. It appears that during the past few years, the world has become a very volatile place in which to live. We have experienced a war in Europe, a pandemic, inflation, rising interest rates, supply chain issues, an opioid crisis, political unrest, and more.

With all this uncertainty, it seems like a good time to invest in a life insurance policy to guarantee that a breadwinner’s family is protected from the financial hardships of premature death or disability. And it is also a good time to invest in an annuity to guarantee that a breadwinner will not outlive his or her assets. So, now could be the best time in history to purchase a life insurance product, and it’s probably the best time to sell one.

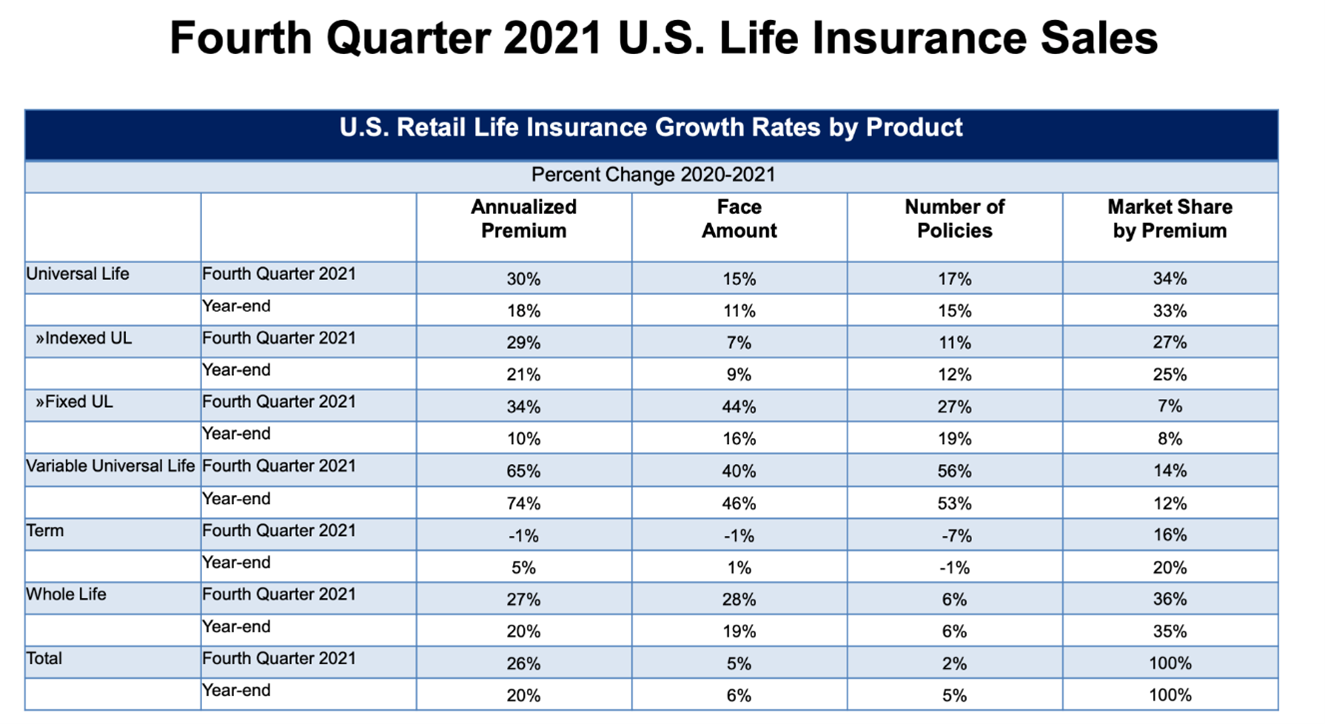

The good news is that the Life Insurance Marketing and Research Association (LIMRA) reported that there was an increase in insurance sales by premium and number of policies in 2021 (see Figure 2).vi

Figure 2

Source: LIMRA's U.S. Retail Individual Life Insurance Sales Survey, Fourth Quarter 2021

But while premium, face amount, and number of policies all increased in 2021 over 2020, the results are a bit disappointing. Not only was the increase in face amount (the most important measure because it depicts actual protection) only 6 percent for the year, but it is greater than the fourth quarter increase, signaling a flattening of sales—what those rearview mirror-facing actuaries would call a negative second derivative.

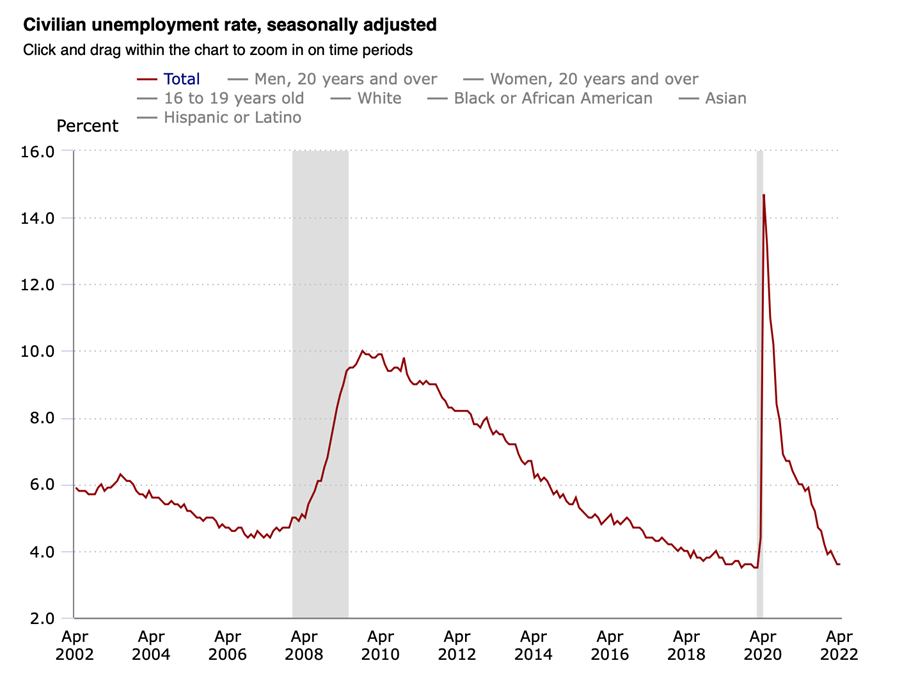

Fear for the economic future cannot be an excuse any longer, as the worldwide jobs market is quite robust. In the U.S., the unemployment rate is at its lowest level in decades, tying lows set prior to the pandemic (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

There are legitimate inflation fears, and the price of gas and oil is high, but people are working and the job market is heated. And as lockdowns ease around the world, with the exception of China, Peloton and Netflix will lose some of their allure and share of wallet. Add to this the fact that, according to LIMRA, intent to purchase life insurance is at a relative high of 31 percent due to mortality awareness caused by the pandemic, and you have a recipe for increased sales.vii

The Right Environment for Life Insurance Sales

So, why aren’t sales skyrocketing? One reason may be the low interest-rate environment. Some people are not interested in pure protection. Having to make the ultimate sacrifice in order to receive a benefit is just not very appealing to many. That is why a traditional life insurance policy in Germany, what we call an endowment policy in the U.S., is the most sold product.

In this type of policy, a lump sum or annual premium is deposited, and the policyowner is guaranteed the return of premium plus interest should he or she live to the maturity date, which typically aligns with retirement age—when social benefits begin. If the policyowner dies before the maturity date, the benefit is the same as he or she would have received at maturity. Additional interest bonuses may be paid if the policy performs well. This type of policy is common in most of continental Europe and very easy to understand. Whether the policyholder lives or dies, the stated benefit will be paid.

The long period of low interest rates led to a steep decline in European life insurance sales, prompting companies to offer cheaper pure protection products. Overall, sales suffered greatly. Now that interest rates are beginning to rise, these products will begin to re-emerge. Hopefully insurers will be slow to offer high guaranteed interest rates on these products; otherwise, they risk the same negative consequences as when rates slumped and remained low for decades.

Because this type of product is so relevant for the European market, but the market adapted to U.S.-type products during the low interest-rate cycle, is it possible that the U.S. market might emphasize this type of product as interest rates rise? Yes, products most relevant to the European market exist in the U.S., but level-term insurance has dominated the sales charts for decades. Some combination of education, marketing, and sales incentives could certainly help.

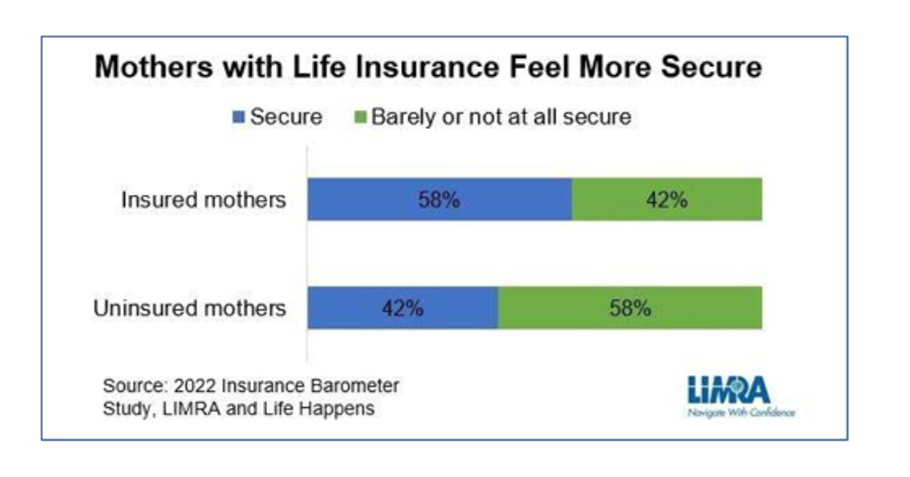

Another idea is to better target mothers. Especially during the pandemic, women were most concerned with family economic security. Women felt much more secure when the family had life insurance in place, according to a LIMRA study (see Figure 4).viii It seems that staying home with children who were attending school remotely and, possibly, having to leave their jobs to do so, caused undue stress for women—who were more likely forced into this position than their spouses. Products designed to alleviate some of this stress could increase sales.

Figure 4

Whatever the products or target market, a world full of volatility may be the perfect setting for selling life insurance, disability, or annuity products. Interest rates are rising, people are back to work, and pandemic fears are easing. Yet memories are still fresh of how quickly life can change for families with little or no protection.

Most business executives reach their elite positions because of leadership, dedication, expertise, foresight, and intelligence. The fact that they identify risks likely to affect business during the next 12 months that have already emerged could be due to many factors:

- McKinsey may only present risks that have already emerged on the list of 15 predetermined choices.

- Business leaders may not want to divulge what they are really focusing on.

- Many executives may choose “safe” answers so they are not “wrong.”

- The more interesting responses may not be in the majority.

Whatever the reason, the real value of the McKinsey study is to identify the ever-changing risks that affect our industry.

Actuaries may look through a rearview mirror every now and then, but they do so to predict future events. Correctly pricing a product is not an easy task, especially when new risks continue to emerge. What the life insurance industry really needs is for business executives, actuaries, agents, underwriters, and other insurance industry professionals to develop new products, marketing techniques, distribution channels, and ideas.

Life insurance is an important product, especially during risky times like the ones we are currently experiencing. The industry needs to reach as many people as possible to make their lives more predictable.

i https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/actuary

ii https://www.beanactuary.org/what-is-an-actuary/what-do-we-do/

iii https://www.soa.org/about/total-membership/

iv https://www.theactuary.com/opinion/2017/12/2017/12/05/strength-numbers

v https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-global-surveys

vi https://www.limra.com/en/newsroom/news-releases/2022/limra-2021-annual-u.s.-life-insurance-sales-growth-highest-since-1983/

vii https://www.limra.com/en/research/research-abstracts-public/2022/2022-insurance-barometer/

viii https://www.limra.com/en/newsroom/industry-trends/2022/mothers-instinctively-want-to-protect-their-loved-ones/

7/2022

About the Author:

Ronnie has over 40 years of insurance and reinsurance experience having worked and lived in 3 countries. In his current role, Ronnie serves as Executive Director to the Bermuda International Long-Term Insurers and Reinsurers (BILTIR) association. He also is a Collaborating Expert of Health and Ageing for The Geneva Association located in Zürich. Ronnie is Co-Chair of the Programming Committee for the ReFocus Conference and served on the Board of Directors of the Society of Actuaries. Before this, Ronnie worked as the Head of Life Reinsurance for Zurich Insurance Group in Zürich, Head of Life Reinsurance for AIG in New York and Global Head of Life Pricing for Swiss Re in London. Ronnie began his career at Mutual of New York. A little-known fact is that Ronnie holds a patent (US20060026092A1) for the first Mortality Bond issued called Vita when he was with Swiss Re.