Mending Long-Term Care Insurance: Understanding, innovation, and trust can revitalize a quintessential insurance product

Robert Eaton, Principal and Consulting Actuary, Milliman

Introduction

The insurance market declared traditional long-term care (LTC) insurance[1] too risky, almost in unison. Some replacement products have cropped up to meet the growing demand—hybrids of life insurance and LTC[2]—but the United States market is far from its equilibrium. Profit and opportunity are on the table and few companies seem willing to take them.

We will bridge this protection gap—true LTC coverage for the mass affluent will be sold and effectuated—when insurers understand the risks and innovate to create new products, and when regulation facilitates modern-day solutions.

There is a virtuous cycle which insurers will recognize: Know your customer, use that knowledge to innovate and build amazing products, and collaborate with regulators as partners to ensure the trust of future customers.

This narrative is subtended by advancements in technology: from AI and robotics to medical innovations and pharmaceuticals.

Background

Insurance provides peace of mind to the policyholder. Unforeseen and catastrophic losses are assuaged with financial benefit and support from insurers. The world today ages with declining birth rates[3] (a natural consequence of economic development and education[4]) and improved mortality through medical advancements and the advent of public goods like fluoride and smoking cessation[5].

The U.S. faces the added pressures of a shrinking working population relative to the dependent population (under 18, and 65+, known as the dependency ratio[6]), stagnating legal immigration, and recent increases and inflation in the cost of goods and services[7].

The foreseeable aging trend, the relative reduction in the labor force and its formal caregivers, and the uncertain costs of providing this care are forces that would generally promote the demand for insurance products to assuage these risks. LTCI was introduced in U.S. the 1970s, and demand for the product yielded a high-water mark of sales in the mid-2000s. The product promises an insurance benefit if people—typically elderly—are unable to proceed with the activities of their daily life[8]. This benefit provides coverage when we’re at our most disadvantaged: when we’re frail and need someone else—someone outside our family or informal caregivers—to care for us. The product’s coverage could increase over time with simple or compound interest or based on the consumer price index (CPI).

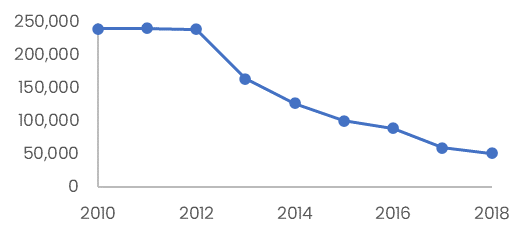

Figure 1: New LTC insurance lives

Source: US Treasury, LIMRA

But sales of LTCI have plummeted[9]. In part, the promise was too good to be true: a level-premium product that protects against so many risks is tough to package. A product that addresses such complex risks is created using a suite of actuarial and economic assumptions: missing substantially on any of them could render the premiums insufficient. In fact, many of these assumptions did not emerge as expected: critically the voluntary lapse rate (and mortality improvement) produced much higher persistency and expected investment returns stagnated approaching and following the Great Recession of 2007-2009. Most company stakeholders view this “traditional” standalone LTC product as too risky to offer, with only a handful of companies still issuing new business[10].

Understand: Know Your Customer

In pulling back on the product generally, and with most companies holding legacy LTCI risks operating in runoff, insurer managers have turned their attention away from the risks of morbidity. As company vision statements are directed elsewhere, LTC insurance business operators manage as best what they can: top line revenue—premium income and investment returns—and expenses. The company’s liabilities, on the other hand, are largely comprised of future claims. LTC insurers have historically managed these claims through traditional levers triggered only at the time of claim itself: ensuring benefit eligibility (reducing fraud), securing a plan of care (reducing abuse), and monitoring ongoing claims.

Only in the past five or six years[11] have LTC insurers given more attention to the actual health of their customers. And it is health (and its decline) of the customer that most portends future LTC claims.

In this sense, LTC insurers rarely understand their true morbidity risks.

Creating a more comprehensive understanding of LTC risks is the foundation for future innovation, product ideation, regulatory acceptance, and the potential fulfillment of a strong demand for LTC insurance.

LTCI claims come as the result of the decline of mind and body: mental impairment and physical inability. Traditional actuarial models rely on past claims experience to forecast future claims, with only modest adjustments for the changing lives and environment of generations of customers. But morbidity is ever evolving. Health plans dedicate vast resources to creating a deep understanding of health, creating disease management programs and working closely with providers to manage the health and care of their members.

Health plans have a different business model from LTCI, and different contractual obligations, but they sit in an adjacent morbidity space. LTC insurers are remiss in ignoring what and how health plans learn from their members. With the help of analytics and deep knowledge of their members through their personal protected health information (PHI), health plans forecast future paid benefits months or even a year or two in advance.

In contrast, armed with no such PHI or regular health information, knowing only the names and mailbox locations of their customers, LTC insurers forecast the next eight decades of claims to calculate their reserves. Today their guides are in aggregate, limited to the slowly emerging experience of a full block of policyholders, and following what other industry datasets say about LTCI morbidity in general.

On one hand, these are the best guides we have available, and we should use them to our best advantage. To succeed in the future, LTC insurers would benefit from a deeper and more current understanding of the health and wellness of their customers, to whom they underwrote and sold policies a decade or two ago. This understanding will equip the LTC insurer to anticipate and manage claims with confidence.

The cost of care is a meaningful actuarial assumption in pricing and reserving for LTCI policies. While there are some policies that indemnify their customers—defining a benefit payment in advance—most policies reimburse customers for actual LTC expenses. LTC is not medical care, nor does it provide other medical therapies; rather, LTC is personal care and the assistance with activities of daily life. The cost of providing this care fluctuates with many factors including (and not limited to): the supply and demand of labor to provide care, the relative cost of goods and services in the economy, advancements in technology, and the cost of running senior housing and facilities such as assisted living, memory care, and nursing homes.

Most insurers understand this cost of care through evaluating their own claims, or from reading survey data[12]. This information is historical, and while most companies attempt to assign causal factors to changes in the cost of care, for simplicity these models of cost trends generally focus on changes in other macroeconomic indicators (e.g.,CPI or Treasury rates).

A more comprehensive understanding of the future cost of care and how to estimate this in the near term is critical to understanding LTC liabilities.

Economy and society

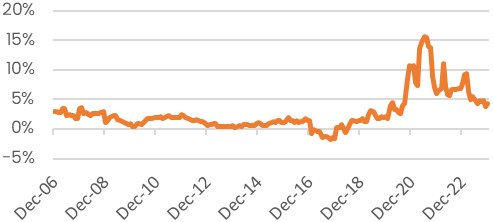

A few years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, home health costs started an alerting rise compared to the sleepy decade before. These costs include the cost of personal care provided in the home (see Figure 2). The inflation of the early 2020s only exacerbated these costs and trends. Most LTC claims start in the home[13], and most of those people don’t transfer out of the home before they die or terminate their claim.

Figure 2: Home Health Care annual trend, component of CPI

Source: BLS.gov

The supply and demand of personal care workers providing formal long-term care directly affects the cost of care. In turn, that supply and demand is influenced by many other economic and societal factors including: the number of workers in the area, the amount of immigration allowed into the country, the cost of living in the area, and more. We view this complex picture only through the lens of one or two figures in our LTC data: the final price of a customer’s care over a period, and how often the claimant received the care.

Societal preferences are different across countries, and they emerge over time within each country. The U.S. was a less mobile society in the early 20th century; more so than today, children chose to live in the communities in which they were raised. The idea of sending an elderly person to a nursing home—a mother or grandmother—was a last resort if there weren’t enough family members around to help. Life expectancies were also shorter, and there were fewer people living to older ages where a lot of LTC is needed. When someone needed paid-for LTC, they usually had a choice of receiving home health care (if there was an agency in the area) or going to a nursing home: the assisted living facility didn’t really come around until the 1990s and dedicated memory care wings until 2000[14].

These rising societal trends are emergent phenomenon often extremely hard to predict[15]. To estimate the likelihood, duration, and cost of LTC even a decade from now is to create a host of

assumptions, most of which point to the past. The LTC claims we have in our historical experience are generally from people born in 1940 and earlier; it is certain that generational changes will impact the way we experience LTC claims in the future. We will likely never have a full understanding of how all these factors interact, but in developing LTCI products we should carry a healthy respect for the variety of forces that are acting on our customers.

Knowing our customers, and fully appreciating the environment in which they will receive LTC, is the most difficult part of the cycle. This new understanding will require advancements in data collection, permissions, and a forging of new consumer trust must come first.

Innovate: Create Amazing Product Experiences

LTCI can be bought today as a stand-alone product (a handful of insurers offer this), as a benefit rider to a life insurance policy, or sometimes as an extended benefit on an annuity. These products provide the guarantee of future LTC coverage, though in large part the benefit remains transactional.

A sample insurer process flow in this customer relationship looks like: market and sell the policy to a 50-year-old couple, collect premiums for a few decades, and pay a benefit when a qualifying claim is filed.

This staccato relationship may work well for other life and retirement products. To thrive, LTCI needs an original approach to the consumer value proposition.

The path to revitalizing LTC can incorporate several concepts:

- A deeper understanding and knowledge of the consumer through modern analytics

- A more continuous relationship between insurer and consumer through state-of-the-art engagement capabilities

- Novel risk management practices that affect both sides of the balance sheet

- Adapting to evolving trends in providing care

Insurers have harvested their data to skillful use for financial and consumer uses, and since the advent of big data and cloud computing, insurers have doubled down on this advantage. The advantage is seen across many fronts: segmenting and

understanding customers for refined marketing, pricing using assumptions derived from predictive models (themselves built on the lessons of traditional actuarial models), and forecasting trends and other environmental variables that affect business.

Some insurance products have taken a natural advantage of larger and deeper data sets and the advanced machine learning and predictive models we lay on top of them. Auto insurers form a distinct profile of customer driving habits, with knowledge of speeding and fast stopping. Safe (less risky) customers put apps on their phones to reap the benefits that insurers are willing to give them for their better behavior.

Health insurers with member PHI use this to great advantage in developing specific forecasts for future health events, and in active management of care. Insurers engage in chronic care management—programs for heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes, for example—that aims to benefit the health insurer (through fewer large health claims) and the member (through improved health).

LTCI may need to incorporate some of these concepts to better understand their customer, and to better anticipate and forestall future catastrophic LTC claims. In an ideal situation, LTC insurers would promote health and wellness programs that benefit the insurer and the policyholder alike. The data and models needed to properly direct such programs don’t exist in any meaningful sense today, but certain insurers are making progress toward this. We should take advantage of Moore’s Law, the falling cost of prediction[16], and the advent of artificial intelligence to better serve our customers (see “Providing Care in New Ways” below for more) with products they will value for life.

Short-duration insurance products and contracts enjoy the ability to engage with customers often—once a year or more. As we saw in the prior section, the insurers take advantage of this engagement to interact with consumers through health and wellness programs, and behavior nudges through apps. LTC insurers today are not in this business, but that doesn’t need to be the case for new products.

Some innovative startup companies have articulated plans to engage with customers for life, and to make insurance offerings and benefits available as consumers age with their family. The concepts are still in their infancy, but they point toward a real opportunity: the LTC insurer-customer relationship is in a bad way today. Reframing this relationship in a positive and constructive light and setting prudent expectations from the beginning (see the “Regulate” section) can produce a stronger and healthier dynamic.

One critical component of LTC that does not impact shorter-duration contracts is the ability to earn interest on the large reserves that build up and support the policy. This serves as a pre-funding mechanism that, combined with the transfer of risk from healthy to riskier, allows LTCI to be as cheap as it is today.

Managing the liabilities themselves through active care planning and management—including the continuity of engagement described here—may reduce a lot of the financial volatility that we see today when we restate actuarial assumptions. There may also be ways to more constructively manage the assets supporting those liabilities, to structure these in a way that anticipates drivers of LTC. Natural hedges, achieved through active financial risk management, can further reduce volatility seen through changing societal trends: rises in the cost of care, and the emergence of new ways LTC is received.

Boston Dynamics’ Atlas humanoid robot

Providing care in new ways

LTC insurers have long relied on the law of large numbers to overcome the rapid evolution of societal norms for providing care. Early LTCI policies anticipated claims primarily from home health and nursing facility settings[17], and the first data sets used for this prediction came from government nursing home surveys. These contracts failed to predict (how could they?) the rise of assisted living facilities and their widespread use in U.S. society[18].

What new care provision are we failing to predict when we write today’s contracts?

There is some flexibility in today’s contracts for an alternate plan of care. Insurers have grappled legally with what LTC contracts were intended to pay, and what they have paid. Nevertheless, a broader care provision construct may be needed for forthcoming modes of care.

One eventuality is that robots will provide some LTC. We already use more computer-aided technology in delivering LTC today than we did in the past 50 years: powered lifts, electronic medication reminders, glucometers, video conferencing tools, etc. The next 50 years will see the greater rise of robotics in our daily lives, including humanoid robotics. The robots will be powered with our new AI interface: the large language models and their derivatives. Already these robots follow commands and perform tasks outside their explicit training data[19][20] [21] [22] [23]. The robots have the capacity to learn, and they will learn (with our help) to provide LTC.

Many people scoff at the idea of a robot providing such personalized care. I propose that for some sensitive daily tasks it is likely that robot-assisted care allows us more dignity, while constant human companionship in between those times will help our emotional fulfillment.

The promise of pharmaceuticals

looms large for LTC insurance

As much as 50% of LTC claims are driven by cognitive decline

Another impending advancement is the development of pharmaceutical therapies for all sorts of conditions that ail us. One silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic was the critical demonstration of our progress in medical biotechnologies such as mRNA vaccines, and we created these in record time[24]. Google DeepMind AI researchers, in their AlphaFold lab[25], are busy predicting the structure and interaction of life’s molecules[26], and the implications are momentous for new drug discovery.

While LTCI today covers primarily personal care, and typically not medical therapies, it is imaginable that drug companies will develop pharmaceuticals that stave off or even prevent mental deteriorations such as Alzheimer's or dementia. Depending on the block of business, actuaries estimate today that 30 percent to 50 percent of all LTC claims are caused in part or whole by mental deterioration (providing substantial supervision due to “severe cognitive impairment” is a required benefit trigger for tax-qualified LTC policies[27]).

As new medical innovations like this arise, and when LTC insurers have a tremendous stake in the outcome, it’s not a stretch to imagine insurers will want to incentivize policyholders to use these therapies for the mutual benefit of company and customer. Even if medical insurance provides some coverage for these new technologies, creating LTCI policies that may cover—or be easily amended to cover—these beneficial advancements will be important for the industry; we will not want to miss the opportunities.

For a given person—say as an example an LTCI policyholder who is also a health plan member, and a father, and a retiree, etc.— there are certain to be complex trade-offs to make regarding his health, and incentives surely won’t always align. We will make progress by talking about everyone’s ecosystem of health and wellness, and how any company may participate, to align incentives in a positive (and profitable) direction.

There are certain to be even more ways that we care for the frail in our society, and the frail of 2050 are not likely to look like the frail of 2010 (who comprise our historical LTC data). Valuable LTC contracts will be flexible and provide the care that is needed in the future.

Plenty of innovation lies ahead for today’s LTCI policies, aided through better analytics, continuous engagement, and flexible policies. A more robust LTC contract—one that does not exist today—will incorporate these new features and possibilities. This will require innovative thinking for legal and compliance professionals.

The elements forestalling this opportunity are: a lack of capital infusion, our current attitudes toward risk, and our regulatory regime. If regulation and risk attitudes shift, then capital will likely follow to meet the market demands.

Regulate: Ensure Ongoing Trust

Working alongside regulators is critical to earning the trust of consumers. Insurers may indeed develop and incorporate these product concepts into new LTC contracts. Some of these innovations are company driven: LTC insurers can choose to write contracts with more flexible and adaptive benefit language that still comports to today’s LTC and life insurer regulations.

Other elements of today’s regulatory environment are less conducive to these innovations, including: the requirement for level pay premiums beyond age 65[1], the approval process for premium rate increases, and the fragmented nature of the statutory system. The U.S. Treasury report on LTCI[2] highlighted similar areas, noting “Regulatory Efficiency and Alignment” as a primary recommendation for revitalizing LTCI.

Given the scrutiny that new LTC policies face on approval, companies will want to form a partnership with regulators that includes education, communication, and transparency. Happily, current regulation[3] does stipulate that—should new providers or services become available—LTC insurers may notify and offer this replacement or exchange coverage to them. This exhibits good foresight, but the hope of this report is that LTC insurance contracts can be built from inception—and operate continuously—to incorporate new care modalities as they emerge without additional regulatory approval.

For new contracts such as this, insurers will want to demonstrate where the value of new product concepts accrues:

- How do risk mitigation tools reduce volatility and improve accuracy?

- Why are changes to benefit and care provisions valuable to consumers?

- How is the company using machine learning and artificial intelligence for the benefit of the customer, and how are biases accounted for?

- How can a company demonstrate that benefits are fair or reasonable in relation to premium?

As with any novel product, insurers will want to communicate regularly as they learn how reality is colliding with their expectations. For a long-term product like LTC, assumptions may take years or decades to emerge. The idea of continuous engagement is intended to accelerate that understanding, but it’s certain the unforeseen trends will emerge.

Conclusion

Most of us will need some LTC in our lives[1], and some of us will need a lot of it. This period can be catastrophic—emotionally, physical, financially—for those in need, and this remains an insurable risk. We now have the tools about us to create and innovate new LTC products that will provide value for decades to come. This will be a critical time in the U.S. to insure against this risk, as our population ages and the supply of formal caregiving may not keep up with the demand.

Insurers and capital committed to this will benefit from our virtuous cycle:

Know your customer, use that knowledge to innovate and build amazing products, and collaborate with regulators as partners to ensure the trust of future customers.

There is a lot of work to be done to realize these innovations and changes; the insurance industry has built up consumer trust for just such an opportunity.

[1] Long-term care insurance is referred to as “LTC” or “LTCI” throughout this report

[2] Individual Life Combination Products Annual Review, 2023 and earlier, LIMRA, LIMRA.com

[3] https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/replacement-level-fertility

[4] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4255510/

[5] Johnson, Steven, Extra Life: A Short History of Living Longer.

[7] 2020-2024 CPI average exceeds the preceding 16 year period: https://www.bls.gov/charts/consumer-price-index/consumer-price-index-by-category-line-chart.htm

[8] bathing, dressing, eating, toileting, transferring, and continence, as defined in IRC 7702B https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/7702B

[9] Long-Term Care Insurance: Recommendations for Improvement of Regulation. US Treasury, 2020. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Report-Federal-Interagency-Task-Force-Long-Term-Care-Insurance.pdf

[10] US Individual Long-Term Care Insurance (Annual Review), 2023 and earlier, LIMRA, LIMRA.com

[11] As a point of reference, the largest industry long-term care insurance conference, the ILTCI (www.iltcifonf.org) introduced the Aging-In-Place educational track at its 2020 annual conference

[12] For example, Genworth publishes a cost of care survey: https://www.genworth.com/aging-and-you/finances/cost-of-care/cost-of-care-trends-and-insights

[13] Milliman 2023 Long-Term Care Guidelines

[14] Gawande, Atul. Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters In the End

[15] Friedrich Hayek summarizes this well in his essay “The Use of Knowledge in Society”: “… the knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess.”

[16] Agrawal, Ajay, et. al., Prediction Machines.

[17] Insuring Long-Term Care, Eaton & Morton, Chapter 2 ‘History of LTC Products’ https://www.actexmadriver.com/orderselection.aspx?id=453149337

[18] Gawande, ibid.

[19] Boston Dynamics, Atlas: https://bostondynamics.com/blog/electric-new-era-for-atlas/

[20] Unitree, G1: https://www.unitree.com/g1/

[21] Xiaomi, Cyber One: https://www.mi.com/global/discover/article?id=2754

[22] Tesla, Tesla Bot: https://www.tesla.com/AI

[23] Agility Robotics, in partnership with Amazon: https://agilityrobotics.com/content/expanded-partnership-amazon

[24] https://www.uclahealth.org/news/article/the-fastest-vaccine-in-history

[25] https://blog.google/technology/ai/google-deepmind-isomorphic-alphafold-3-ai-model/

[26] “Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3”, Abramson, et. al. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07487-w

[27] IRC 7702B (c) (2) (A) (iii) https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/7702B

[28] NAIC Long-Term Care Insurance Model Regulation Section 6.F. and Section20. https://content.naic.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/MDL-641.pdf

[29]Long-Term Care Insurance: Recommendations for Improvement of Regulation. US Treasury, 2020. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Report-Federal-Interagency-Task-Force-Long-Term-Care-Insurance.pdf

[30] NAIC Long-Term Care Insurance Model Regulation Section 26. https://content.naic.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/MDL-641.pdf

[31] “… 70% of adults who survive to age 65 develop severe LTSS needs before they die and 48% receive some paid care over their lifetime.” From “What Is the Lifetime Risk of Needing and Receiving Long-Term Services and Supports?” Urban Institute, 2019. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/what-lifetime-risk-needing-receiving-long-term-services-supports-0