Social Inflation: Evidence and Impact on Property-Casualty Insurance

White Paper by The Institutes

Over the last several years, the property-casualty insurance industry has experienced deteriorating results in several liability-related lines. Industry analysts, CEOs, and trade journalists point to “social inflation” as a principal reason for the deterioration and are warning of its effects on future earnings.1 While much of the discussion has focused on commercial liability insurance lines, including commercial auto, medical malpractice, and general liability, concerns are now being raised that social inflation is starting to affect liability coverages in personal lines. In this white paper, we clarify what social inflation is and explore existing evidence documenting its scope and effects, with the understanding that social inflation is, to a significant degree, a multidimensional manifestation of specific socioeconomic and civil justice systems and processes.

There is little doubt that the coronavirus pandemic now engulfing the world will affect social inflation and all of its several parties and trends, but whether it will serve to mitigate or aggravate social inflation simply is not known. The analysis that follows is based on data and trends existing prior to the emergence of the pandemic. An assessment of the pandemic’s impact will surely come as more is learned about how individuals, organizations, and the civil justice system alter behavior in response to the progression and consequences of the pandemic. No attempt is made here to assess or estimate those changes or the impact of the pandemic on social inflation, although it is noted that the effort to impose coverage for economic losses under business interruption insurance policies, despite contract provisions excluding coverage for virus-related loss, represents a current example of how some state legislatures have participated in the social inflation phenomenon.

____________________________________

1Angela Childers, “Travelers Reports Profit Jump, but 'Social Inflation' Weighs,” Business Insurance, January 23, 2020, https://www.businessinsurance.com/article/20200123/NEWS06/912332708/Travelers-insurance-fourth- quarter-results-social-inflation# (accessed May 26, 2020); Assured Research Series: Social Inflation is Back!, Assured Research, LLC, February 4, 2020, https://www.genesisinsurance.com/assets/pdfs/Insights/ Assured%20Research%20on%20Social%20Inflation%20Feb%202020.pdf (accessed May 26, 2020).

What Is Social Inflation?

Social inflation refers to recent growth in liability risk and costs due to several trends and developments, including:

- Changes in underlying beliefs about the appropriateness of filing lawsuits and expectations of higher compensation

- Rollbacks of previously enacted tort reforms intended to control costs

- Legislative actions to retroactively extend or repeal statutes of limitations

- Increased attorney advertising and increased attorney involvement in liability claims

- The emergence and growth of third-party litigation financing

- Increasing numbers of very large jury verdicts, reflecting an increase in juries’ sympathy toward plaintiffs and in their willingness to punish those who cause injury to others

- Proliferation of class-action lawsuits

Social inflation has resulted in rapid increases in claim costs for key liability insurance lines— most notably commercial auto liability. In this white paper, claim loss data published by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) are examined to document incurred loss trends in several key insurance lines. As will be shown, recent incurred losses have accelerated rapidly in the last five to six years—much more rapidly than in the preceding five to six years and much more rapidly than economic inflation would suggest or explain.

At its heart, social inflation begins with changes in attitudes and beliefs about entitlement to compensation for injury or loss and the willingness to pursue litigation or file an insurance claim against another individual or business in order to obtain that compensation. In this paper, we review recent research for evidence describing public views about filing personal injury lawsuits, and we consider whether changes in attitudes about lawsuits may be based in part on general views of personal entitlement. We also examine public sentiment toward “big business” and whether recent changes in these views might influence the public’s willingness to file lawsuits. The idea that growing income inequality in the United States is fueling the spread of anti-corporate attitudes and generating feelings of anger that lead to changes in claiming behavior and expectations of higher levels of compensation also will be considered.

The commencement of a personal injury lawsuit depends on the motivation and ability of a plaintiff to initiate the formal litigation process. However, before commencing a lawsuit, an individual must first obtain the services of an attorney. We will review the extent to which attorneys are involved in compensation systems designed to work largely without the involvement of attorneys and lawsuits. We also will review the rapid increases in attorney advertising and consider how the trend may be contributing to social inflation.

There are many obstacles to filing a lawsuit, including procedural and substantive rules and requirements designed to clarify the circumstances in which compensation is allowed and provide for the fair and effective functioning of the civil justice system. We will review evidence indicating that expansive court interpretations and legislation have eroded many of the civil justice system’s procedural and substantive rules and requirements. The result has been to encourage lawsuits that otherwise would not be filed.

Another trend frequently associated with social inflation is growing settlement costs as juries become increasingly sympathetic to plaintiffs’ claims and award significantly higher damages as a means to punish perceived wrongdoers. While most lawsuits are settled prior to trial, the few cases that do go to trial and result in jury verdicts have a strong signaling effect during negotiations that ultimately end in higher average settlements. Trends in claim severity are reviewed.

An often-mentioned reason for higher jury awards is the explosive growth in third-party litigation funding, in which outside investors provide financial resources to plaintiffs in exchange for a percentage of any settlement or jury award. Litigation funding is believed to remove much of the incentive plaintiffs face to settle lawsuits in a timely manner and "hold out" for larger settlements. Evidence documenting these trends will be discussed.

Social inflation describes the combined effects of all these trends and developments, with increased liability costs as the resulting consequence. Before examining the factors and conditions contributing to social inflation, we first examine social inflation's effects on incurred insurance claim costs. Social inflation’s impact on claim costs ultimately leads to higher insurance costs for all consumers.

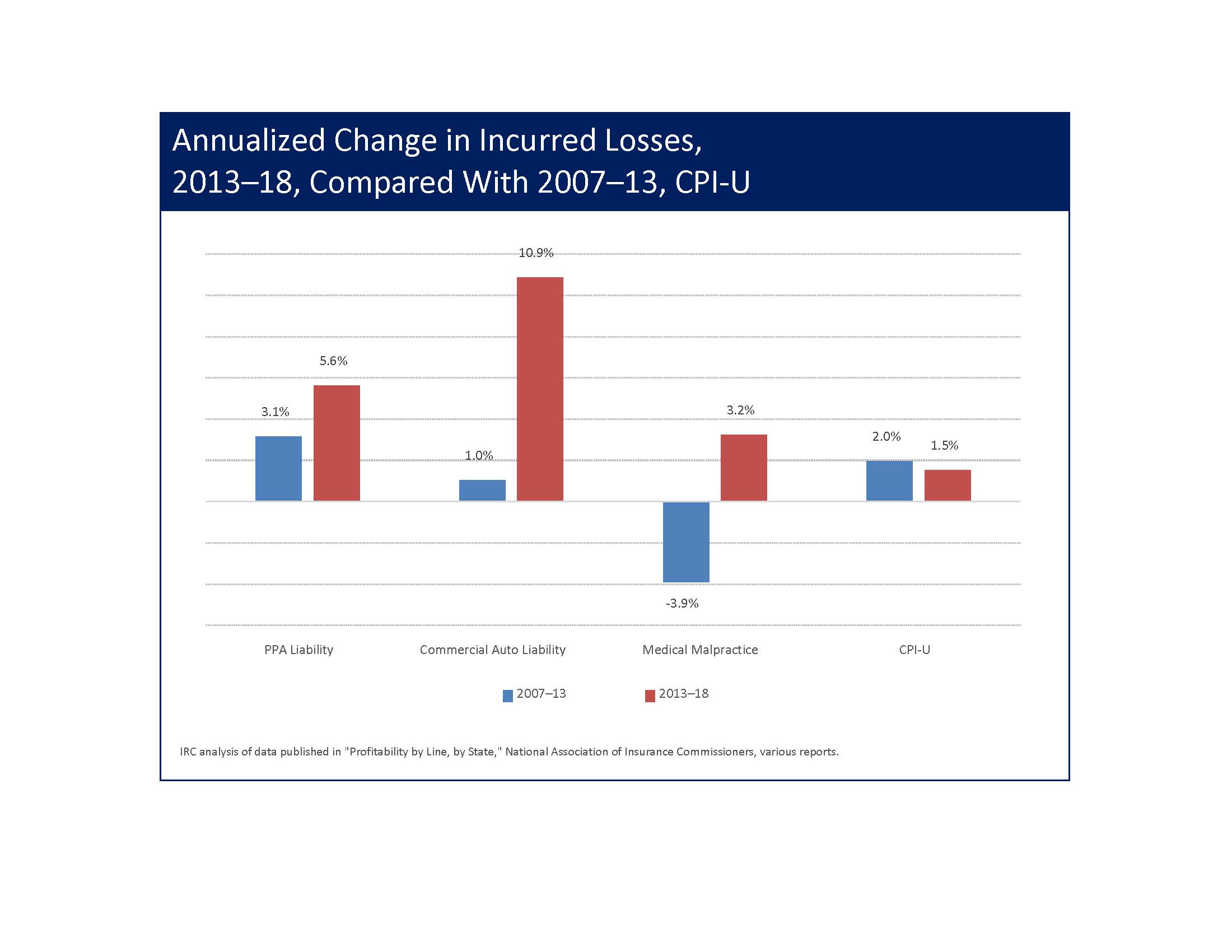

Property-Casualty Insurance Trends

Based on IRC’s analysis of data published by the NAIC, incurred claim losses have increased rapidly in recent years—much more rapidly than in preceding years and more rapidly than economic inflation would predict.2 The data also indicate that personal auto liability may be affected by the same social inflation trends that are affecting commercial liability insurance business. As shown in the following chart, commercial auto incurred losses increased at an annualized rate of 5.4 percent from 2007 through 2018. However, almost all of the increase over that 12-year period actually occurred during the second half of the period. From 2013 through 2018, commercial auto claim losses increased at an annualized rate of 10.9 percent, compared with a 1.0 percent annualized rate from 2007–13. Also, while inflation over the 12- year period averaged only 1.8 percent, the annualized inflation rate from 2013–18 was 25 percent less than the annualized rate from 2007–13.3 Medical malpractice insurance experienced similar trends. Over the 12-year period, 2007–18, incurred claim losses declined at an annualized rate of 0.7 percent. However, during the second half of the study period, incurred losses increased at an annualized rate of 3.2 percent—more than twice the annualized rate of inflation. Private passenger auto (PPA) liability claim loss trends follow the same basic pattern as commercial auto and medical malpractice, although the impact of social inflation has been more muted. Over the 12-year period, incurred claim losses increased at an annualized rate of 4.3 percent—more than twice the rate of price inflation.

____________________________________

2NAIC, Profitability by Line by State, various reports.

3We acknowledge that the 2007–13 period includes the 2008–09 recession and the initial years of recovery, which may have influenced outcomes and trends discussed here.

Auto liability claim losses increased almost twice as rapidly from 2013–18 (5.6 percent) as from 2007–13 (3.1 percent). The difference represents a substantial increase in claim loss growth, even though the increase was not as great as in commercial auto and medical malpractice. That the impact of social inflation is more muted with PPA liability than with the other lines of insurance may be due to the fact that defendants and at-fault parties in auto liability claims and lawsuits are less likely to be viewed as having deep pockets than are defendants and at-fault parties in the other lines.

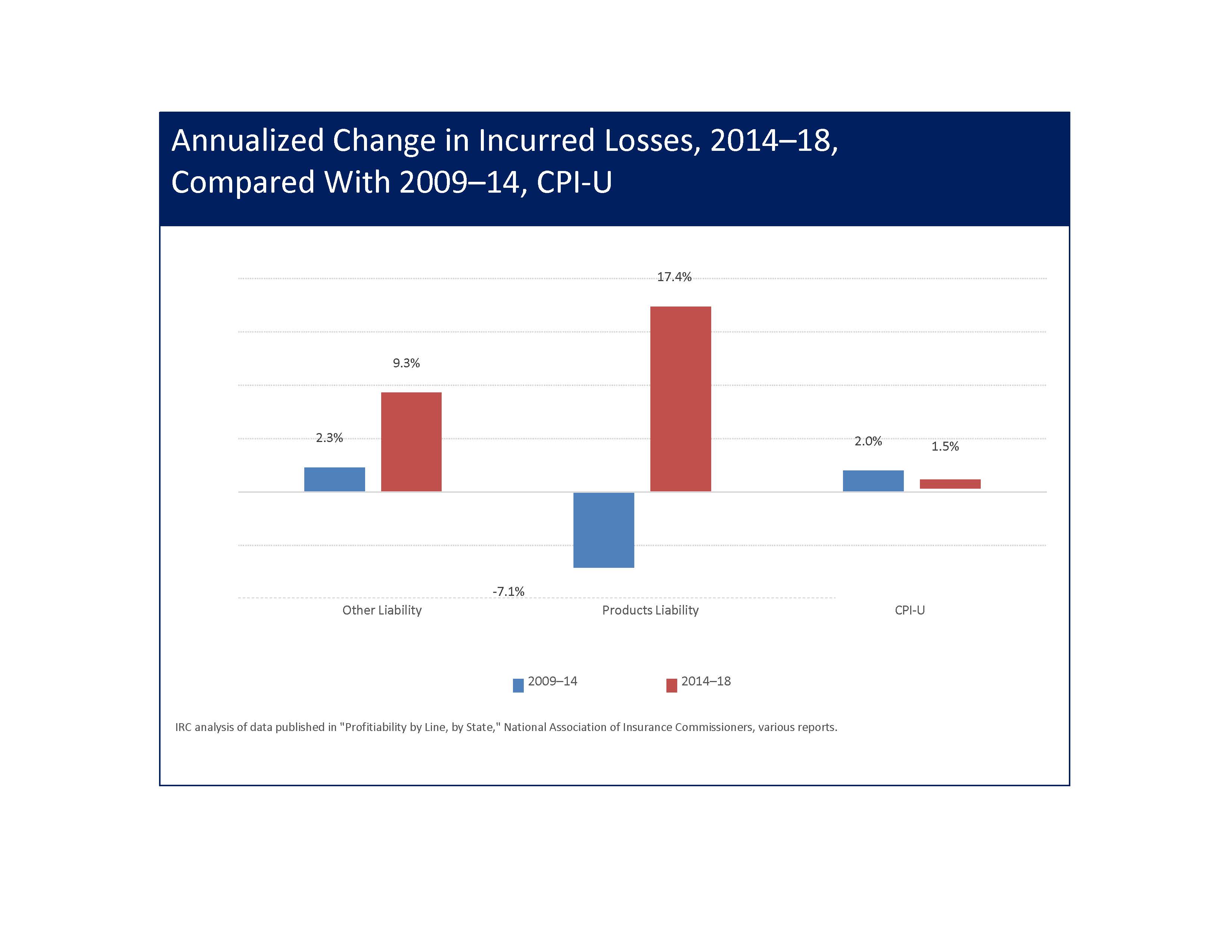

Two other commercial insurance lines significantly affected by social inflation trends are products liability and other liability.4 Recent loss trends in these lines are also examined using NAIC data, but changes in data reporting require a slightly different time frame. Prior to 2009, products liability experience was included with the other liability experience reported by NAIC. Since 2009, the NAIC has reported products liability experience separately. Therefore, the time period examined for these lines is 2009 through 2018. As shown below, during the second half of that 10-year period, products liability incurred losses increased at an annualized rate of 17.4 percent—more than five times the rate of inflation. From 2009–14, products liability incurred claim losses decreased at an annualized rate of 7.1 percent. Other liability incurred losses also

____________________________________

4"Other liability" is a collection of smaller liability insurance coverages including, for example, commercial general liability. Most of the insurance products included in this category are sold to commercial entities or individuals providing professional services.

experienced more rapid increases in the second half of the 2009–18 period. Other liability incurred losses increased at an annualized rate of 9.3 percent from 2014–18—four times the rate of increase from 2009–14.5

The claim loss trends and experience reviewed above are consistent with anecdotal observations and concerns about the impact of social inflation on insurance claim costs. We turn now to examining the underlying factors and conditions generating these costly increases in insurance losses.

Underlying Attitudes and Opinions

Income inequality in the U.S. is well documented and widely acknowledged. According to the Pew Research Center, from 1970 through 2018, the share of aggregate income held by lower- income households went from 10 percent to 9 percent, while the share flowing to upper- income households jumped from 29 percent to 48 percent. Sixty-one percent of US adults surveyed in 2019 said there’s “too much” economic inequality in the United States. Among those who said there was too much inequality, 67 percent said that “major changes” were needed to address the issue. Fourteen percent said that addressing economic inequality would require the “complete rebuilding” of the economic system, and 62 percent said that large businesses and corporations had “a lot of responsibility” in reducing inequality.6

____________________________________

5Supra, note 3.

6Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Ruth Igielnik and Rakesh Korchhar, “Most Americans Say There Is Too Much Economic Inequality in the U.S., but Fewer Than Half Call It a Top Priority,” Pew Research Center, January 9, 2020, https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/01/09/most-americans-say-there-is-too-much-economic-inequality-in- the-u-s-but-fewer-than-half-call-it-a-top-priority/ (accessed May 26, 2020).

In addition to believing that economic inequality is a major problem, many Americans are also angry. In its 2019 annual report on emotional states around the world, Gallup reported that 22 percent of Americans reported feeling angry “during a lot of the day yesterday”—the highest level of anger measured by Gallup in more than a decade. Gallup’s survey did not ask specifically what respondents were angry about, but it confirmed that on any given day, one in five Americans is angry much of the time.7 The importance of this finding is supported by research from 2002 that found that individuals with higher levels of anger reactivity were more likely to file personal injury lawsuits.8

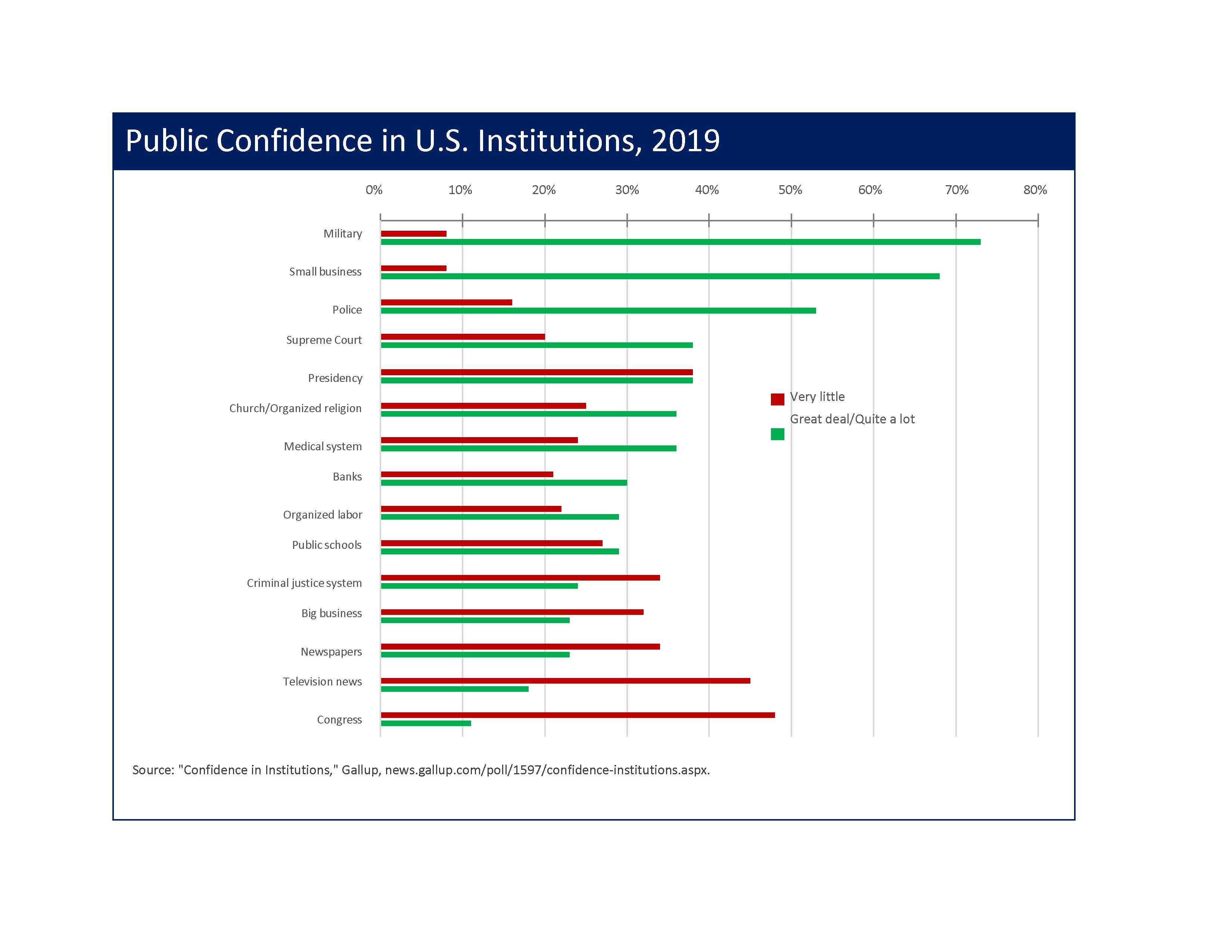

Compared with other major private and public institutions, “big business” ranks low in terms of public confidence. According to Gallup, only newspapers, television news, and Congress were viewed with less confidence than big business in 2019. And over the last 20 years, public views toward big business have gotten worse. From 2000 to 2019, the percentage expressing “very

____________________________________

7Julie Ray, “Americans’ Stress, Worry and Anger Intensified in 2018,” Gallup, April 25, 2019, news.gallup.com/poll/249098/americans-stress-worry-anger-intensified-2018.aspx (accessed May 26, 2020).

8M.A. Lindberg, The Role of Suggestions and Personality Characteristics in Producing Illness Reports and Desires for Suing the Responsible Party, The Journal of Psychology, Volume 136 (2), 2002, pp. 125-140.

little” confidence in big business grew from 22 to 32 percent, while those expressing a “great deal/quite a lot” of confidence dropped from 29 to 23 percent.9

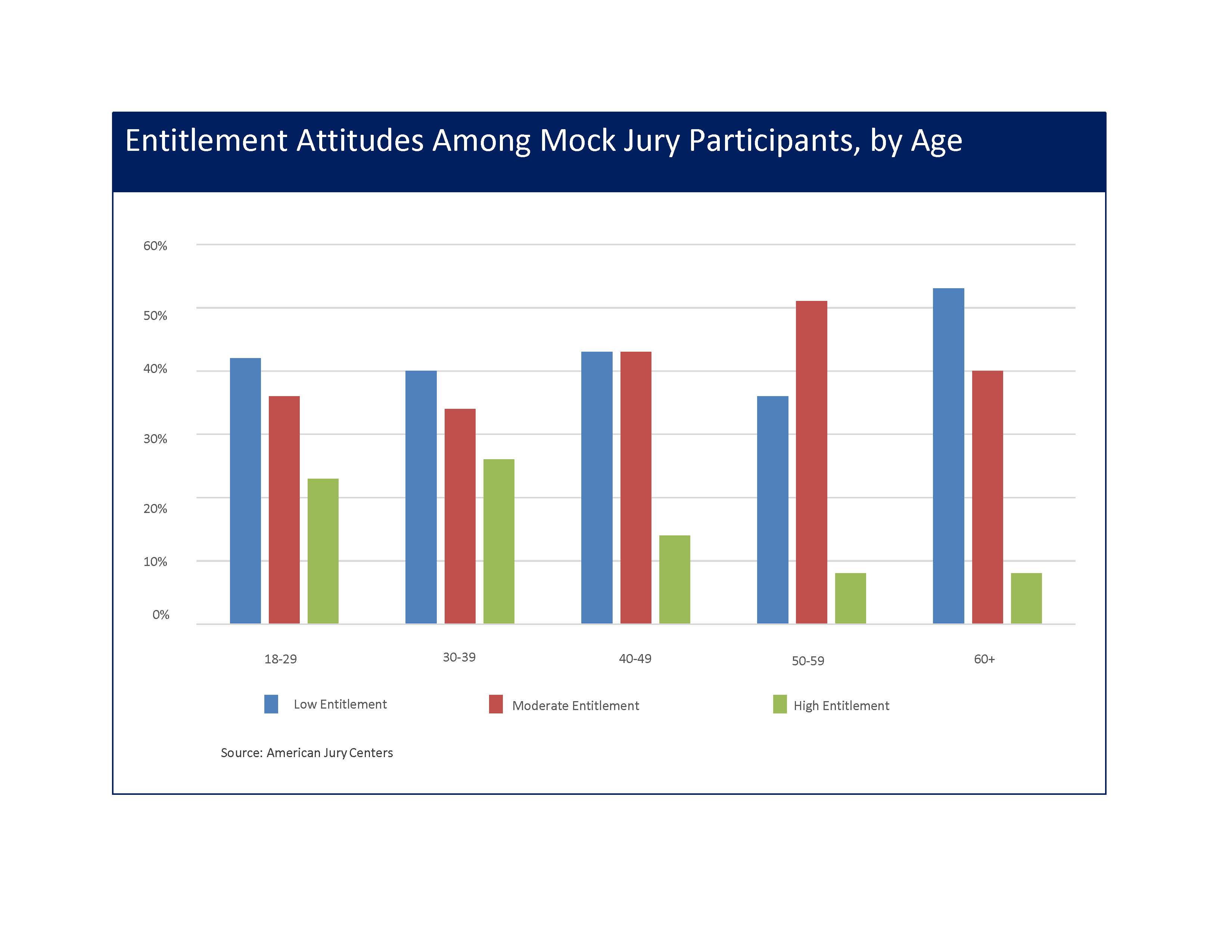

Despite numerous anecdotal reports, there is little direct evidence about general attitudes of entitlement. Research on entitlement attitudes and jury behavior, however, provides indirect evidence that entitlement attitudes may indeed be increasing throughout the general population. Since 2009, American Jury Centers has asked mock jury participants their agreement with the following key questions from the Psychological Entitlement Scale:

- I honestly feel I’m more deserving than others.

- I deserve more things in my life.

- People like me deserve an extra break now and then.

Responses to the questions are used to classify mock jury participants as having low, moderate, or high entitlement attitudes. Participants in the 18-29 and 30-39 age groups were much more likely than older participants to be classified as having high entitlement attitudes. Similarly, Participants age 60 and above were much more likely to have low entitlement attitudes than younger participants.10

It is unclear whether younger individuals with high entitlement attitudes will retain those attitudes as they age or develop the low entitlement attitudes of their elders. It is also unclear where generations yet to come will fall on the entitlement-attitude spectrum. In any event, the findings from this study are consistent with many anecdotal reports that millennials and Gen Xers have strong feelings and attitudes of entitlement and suggest that such feelings may become more commonplace throughout the general population.11

____________________________________

9Gallup, Confidence in Institutions, news.gallup.com/poll/1597/confidence-institutions.aspx (accessed May 26, 2020).

10Gary Giewat, Damage Awards: Jurors’ Sense of Entitlement as a Predictor, The Jury Expert, May 30, 2011 (accessed April 27, 2020).

11Jean M. Twenge, “Do Millennials Have a Lesser Work Ethic?”, Psychology Today, www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/our-changing-culture/201602/do-millennials-have-lesser-work-ethic (accessed May 26, 2020).

Tort Reform Rollbacks

Over the last several decades, many states have enacted tort reforms intended to enhance the predictability, stability, and affordability of state civil justice systems. A centerpiece of many tort reform efforts have been limits on compensation for non-economic damages, often referred to as pain and suffering. According to one account, 38 states had enacted caps on non- economic damages by 2019. (In six states, caps applied to economic as well as non-economic damages.) Caps on non-economic damages have been found to be especially effective in controlling tort liability costs.12

Caps on non-economic damages have been fiercely opposed by trial lawyers representing personal injury claimants. The supreme courts of at least eight states with caps on non- economic damages have overturned the reforms. By overturning key tort reforms, the courts have reintroduced the same cost-inflating trends that were the impetus for enacting the reforms in the first place. And by increasing the potential damages in the claims and lawsuits involved, additional incentive is created for more lawsuits to be filed and for claimants and plaintiffs to seek higher settlements from insurers and defendants.

Legislative Actions Expanding Liability

A statute of limitation is a statutory time frame during which a person may file a personal injury lawsuit; after the statute of limitation has expired, a plaintiff is barred from filing a lawsuit. All states have statutes of limitations for filing personal injury lawsuits, with the specific range of time varying according to the type of injury or claim involved. For automobile accidents, for example, statutes of limitations range from one to six years.13

There have been multiple instances where state legislatures have extended or attempted to extend statutes of limitations and retroactively apply the new time limit to claims whose statute of limitation had expired. Retroactive extensions of statutes of limitations create additional liability and costs that were not contemplated when an insurance policy was originally issued and priced. A highly visible example of attempts to retroactively change statutes of limitations involves allegations of sexual abuse made by victims who did not come forward to press their claims until much later in life. Several states have debated changes designed specifically to provide access to potential compensation by changing the beginning of the period of time within which a lawsuit must be filed from the time of the alleged injury to the time injury was discovered by a claimant.14 In a few states, retroactive changes were enacted into law but face challenges questioning their constitutionality.15

Another example of legislative enactments resulting in the expansion of potential liability is happening now as several states consider legislation requiring insurers to accept claims for losses related to the COVID-19 pandemic under business interruption coverage, despite explicit insurance policy provisions excluding coverage for losses due to virus or bacteria.16 The financial impact of such actions would be catastrophic for affected insurers. Although no state legislature has yet to enact such a requirement, the possibility that one or more might do so is being taken very seriously by the insurance industry.17

Attorney Advertising and Increased Involvement in Liability Claims

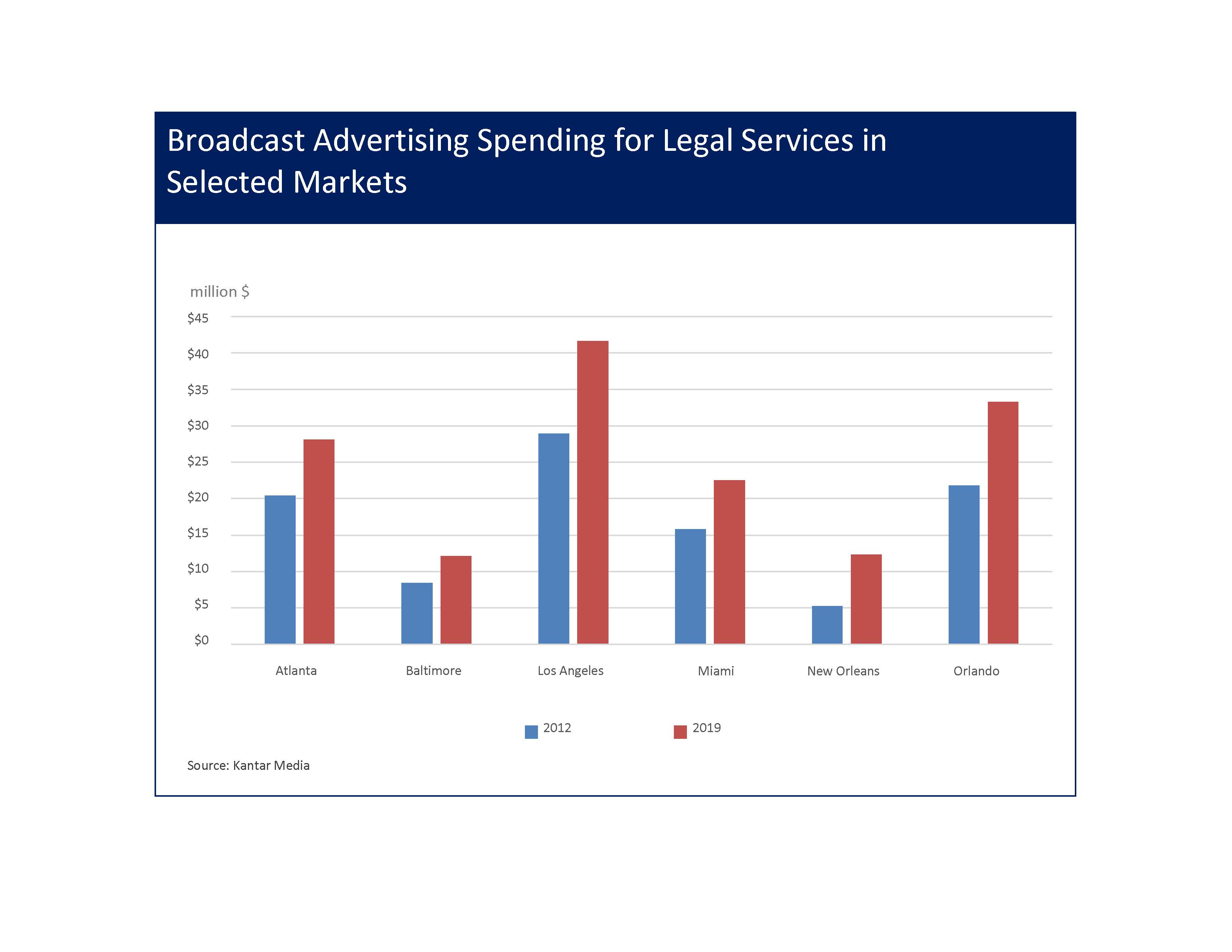

Dramatic increases in attorney advertising have led to more frequent attorney involvement in some types of insurance claims, increases in claim frequency, and expectations of larger settlements and jury awards. Attorney advertising has increased rapidly since the 1977 Supreme Court ruling in Bates v. State Bar of Arizona, but it is believed to have accelerated even more significantly in recent years. From 2012–19, broadcast television ad spending for legal services increased 44 percent in the Baltimore television market, 44 percent in Los Angeles, and 42 percent in Miami. Spending on television advertisements for legal services more than doubled in New Orleans (137 percent) and increased rapidly in Atlanta (38 percent) and Orlando (53 percent). In a 2005 study, one researcher found that the return on advertising investment by law firms was four to six times the cost.18 The return on investment may be much higher now than in 2005.

____________________________________

12Leonard J. Nelson III, Michael A. Morrisey, and Meredith L. Kilgore, Damages Caps in Medical Malpractice Cases, The Milbank Quarterly, 2007, Vol. 85(2), 259-286.

13“Car Accidents: Statutes of Limitations,” Enjuris, www.enjuris.com/car-accident/statutes-of-limitations.html (accessed May 26, 2020).

14Marisa Kwiatkowski and John Kelly, “The Catholic Church and Boy Scouts are Lobbying Against Child Abuse Statutes. This Is Their Playbook,” USA Today, October 2, 2019, https://www.usatoday.com/in- depth/news/investigations/2019/10/02/catholic-church-boy-scouts-fight-child-sex-abuse-statutes/2345778001/ (accessed May 26, 2020).

15Connecticut and Pennsylvania are two examples. Related to the constitutionality of Pennsylvania's enactment, see Anna Orso, “In Historic Move, Pa. Legislature Passed Clergy Abuse Reforms. Here’s Why They’ll Have to Do Part of It Again,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 26, 2019, www.inquirer.com/politics/pennsylvania/pennsylvania- child-sexual-abuse-bill-statute-of-limitations-legislature-20191121.html (accessed May 26, 2020).

16“Proposed N.J. Bill Would Require Insurers to Pay COVID-19 Business Interruption Claims,” Insurance Journal, March 19, 2020, www.insurancejournal.com/news/east/2020/03/19/561643.htm, (accessed May 26, 2020).

17“COVID-19 and the Mutual Insurance Industry,” National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies, March 27, 2020, www.namic.org/news/releases/200327mr01 (accessed May 26, 2020), and “NAIC, IAIS, and AM Best: Mandating Retroactive Business Interruption Insurance Could Harm Consumers,” American Property Casualty Insurance Association, May 11, 2020, www.pciaa.net/pciwebsite/cms/content/viewpage?sitePageId=60726

(accessed May 26, 2020).

18H.R. Moser, “An Empirical Analysis of Consumers' Attitudes Toward Legal Services Advertising: A Longitudinal View,” Services Marketing Quarterly, volume 26 (4), pp. 39-56.

The increases in broadcast television spending occurred during a dramatic shift in advertising overall from traditional platforms, such as television and print, to online digital platforms. According to eMarketer, 2019 was the first year in which spending on digital advertising exceeded traditional ad spending, and by 2023, digital ads are projected to represent two- thirds of all ad spending.19 Overall digital ad spending for legal services is unknown. However, there is evidence suggesting that law firms are spending large sums when it comes to attracting potential clients in class action lawsuits and mass torts on digital ads, especially.

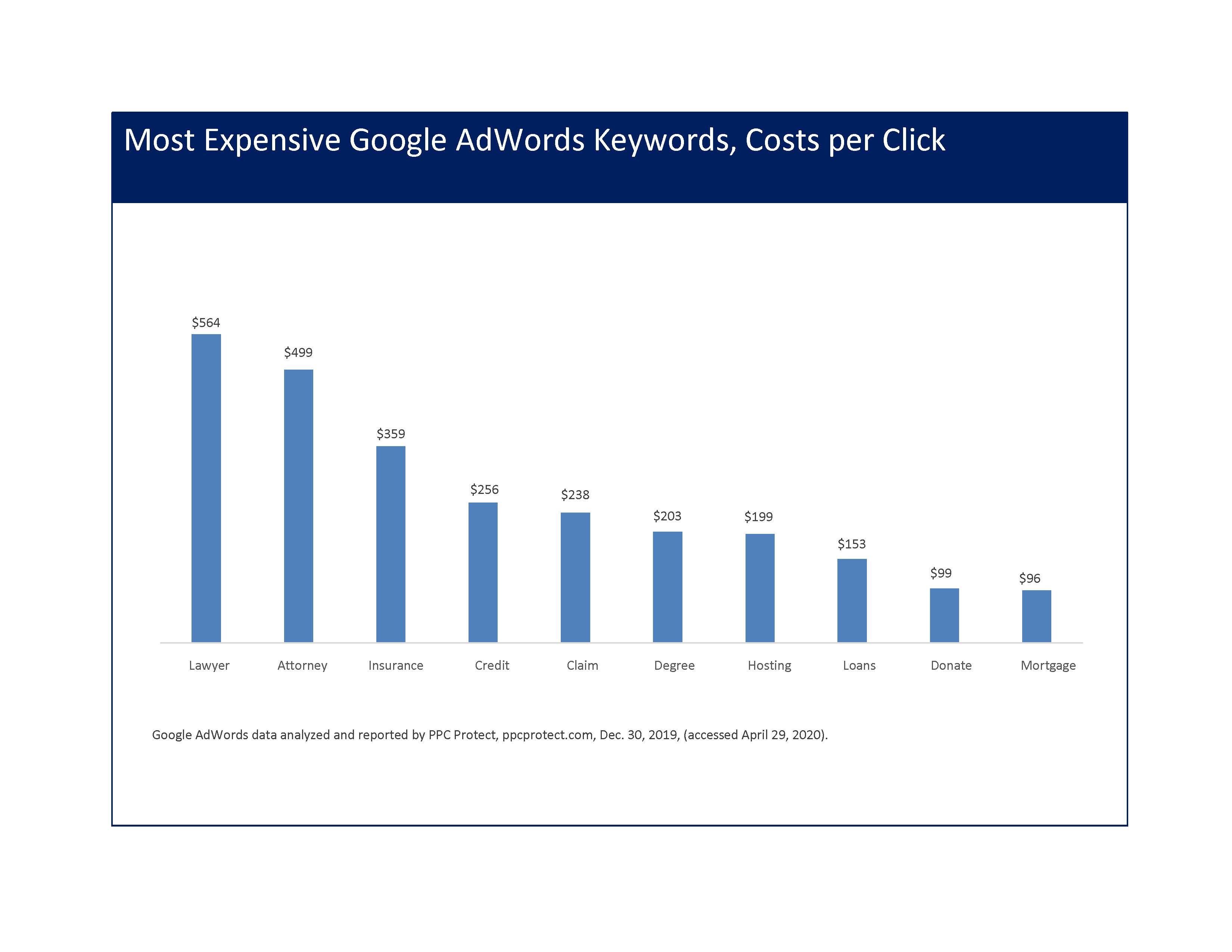

Businesses, including law firms, pay to have their ads displayed by online search engines and other websites (publishers)—Google and Facebook, for example. Under a pay-per-click approach, firms pay the website publisher each time the firm’s ad is displayed and someone clicks the ad. The amount paid per click is based on the market value of the ad space and is determined by the website publisher or a third party, such as Google AdWords. According to PPC Protect, an online marketing security firm, the prices per click paid by law firms for online advertising are the highest prices paid by any advertisers.20 The most expensive specific keyword phrases under the "lawyer" category are "car accident lawyer moreno valley" ($584.44), "Ft. Lauderdale car accident lawyer" ($566.17), and "auto accident lawyers in Chicago" ($542.95).

__________________________

19Jasmine Enberg, “US Digital Ad Spending 2019,” eMarketer, March 28, 2019, www.emarketer.com/content/us- digital-ad-spending-2019 (accessed May 26, 2020).

20Sam Carr, “The Most Expensive AdWords Keywords,” PPC Protect, Dec. 30, 2019, ppcprotect.com/most- expensive-adwords-keywords (accessed May 26, 2020).

Research confirms that attorney advertising cultivates positive consumer attitudes toward personal injury litigation. In a 2014 paper, Deidre Pettinga, of the University of Indianapolis, found that "favorable attitudes toward plaintiff's attorney advertising are positively, statistically correlated with favorable attitudes toward the act of filing a personal injury lawsuit."21 In addition to confirming the role of attorney advertising, Pettinga found vengeful attitudes, measured using accepted research tools, also to be statistically related to positive attitudes toward personal injury litigation, giving additional credence to the role anger plays in prompting personal injury lawsuits, as discussed earlier.22

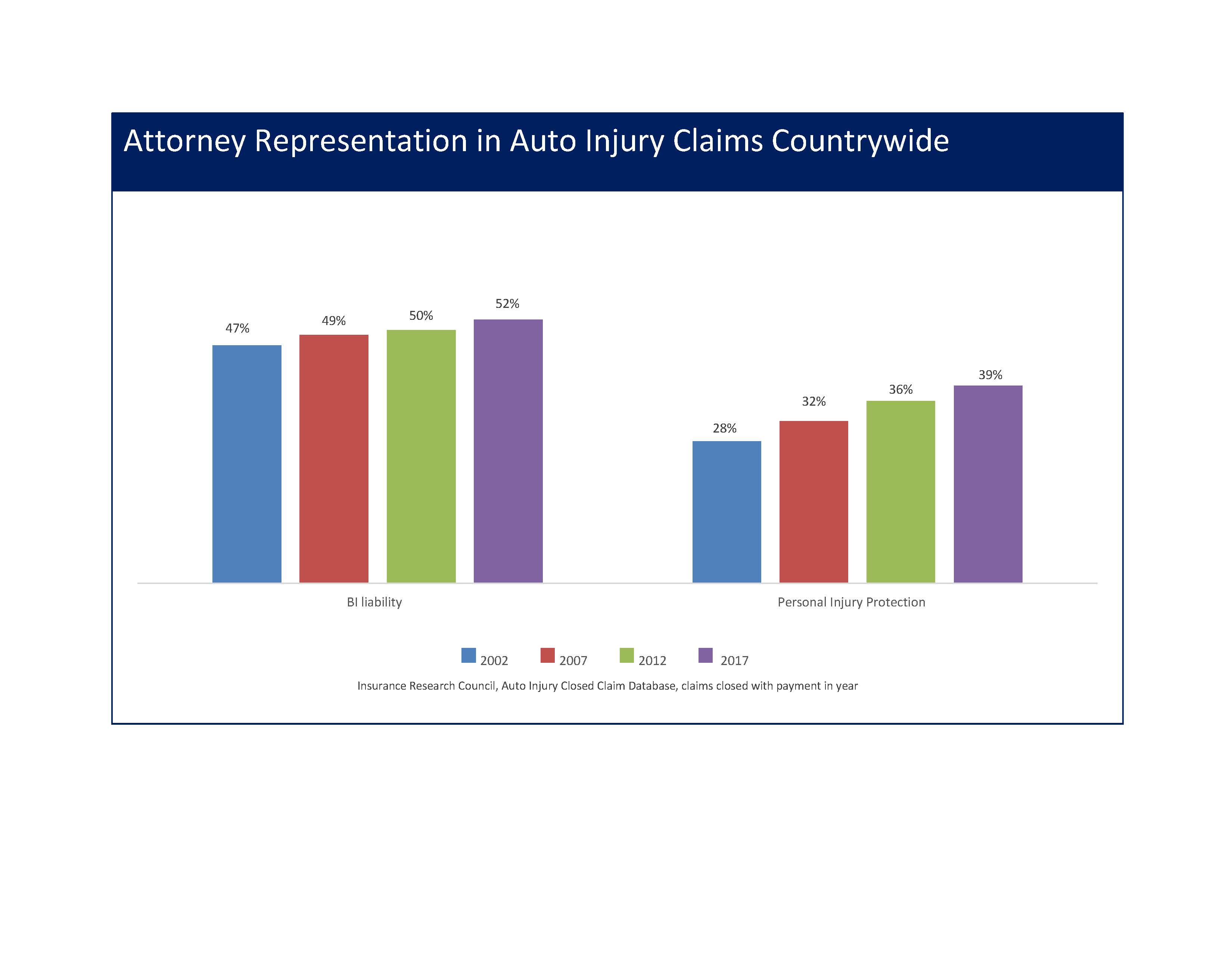

A direct consequence of increased attorney advertising has been more frequent attorney involvement in widely used insurance programs, including programs originally designed to substantially reduce, if not eliminate, attorney involvement. Bodily injury (BI) liability auto insurance claims have seen a steady increase in attorney representation, from 47 percent of all claims countrywide in 2002 to 52 percent in 2017. Personal injury protection (PIP) claims in no- fault states have experienced an even more rapid increase in attorney involvement, growing from 28 percent in 2002 to 39 percent in 2017. The increase in attorney involvement in PIP claims is particularly concerning in that PIP no-fault insurance programs were designed and intended to eliminate most attorney involvement and to more efficiently deliver appropriate compensation to motor vehicle accident victims.23The failure of these systems to eliminate most attorney involvement is no more evident than in Florida, which, in 2017, had an attorney

______________________________

21Deidre M. Pettinga, “Examining Consumers' Attitudes Toward Personal Injury Litigation,” International Journal of Business and Social Science, Vol. 5 (2), Feb. 2014, pp. 48-57.

22N. Stuckless and C. Goranson, “The Vengeance Scale: Development of a Measure of Attitudes Toward Revenge,” Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, Vol. 7(1), 1992, pp. 25-42.

23Robert Keaton and Jeffrey O’Connell, Basic Protection for the Traffic Victim: A Blueprint for Reforming Automobile Insurance, (Boston: Little, Brown & Company), 1965.

involvement rate in no-fault PIP claims (55 percent) that was higher than the average attorney involvement rate for BI liability claims countrywide (52 percent).24

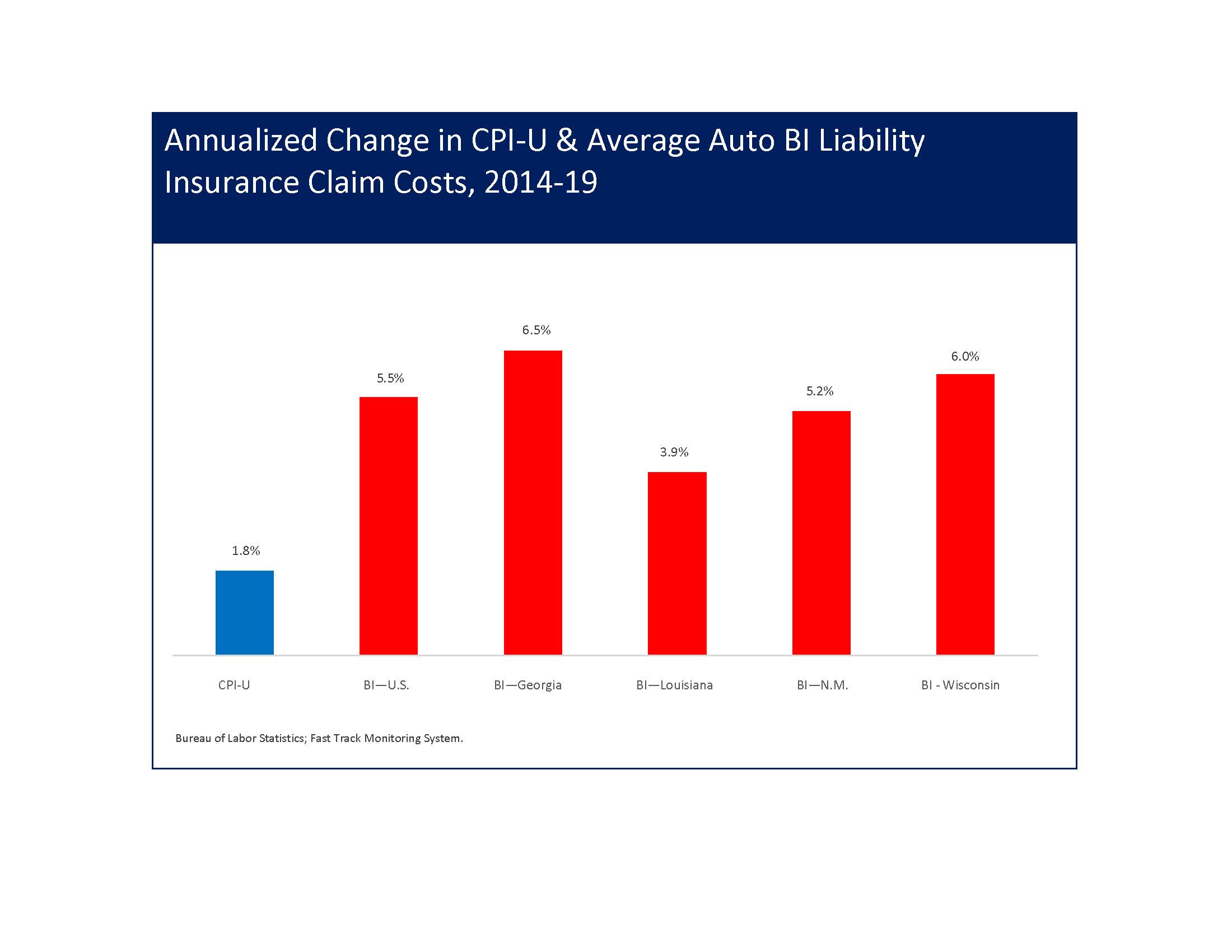

Recent trends in BI liability claim severity suggest that social inflation may be contributing to a recent sharp increase in the average cost of auto injury liability claims. From 2014–19, the average payment for BI claims countrywide grew at an annualized rate of 5.5 percent—three times the rate of inflation. Claim severity trends vary considerably across states and are influenced by factors other than social inflation, such as differences and changes in the utilization and cost of medical services. Changes in claim frequency resulting from advanced accident-avoidance features may also affect claim severity trends. Additional research is needed to help understand the relative contribution of social inflation and these other factors.

In its countrywide studies of auto injury claims, the Insurance Research Council has documented the costly consequences of attorney involvement. IRC compared claimed economic losses and insurance payments for similar groups of BI liability claimants (those with no hospital or emergency room treatment, no lost time from work, and no permanent total disability). For claimants with similarly serious injuries, those represented by attorneys received, on average, less in reimbursement after all medical expenses and attorney fees were subtracted from the final settlement, even though the final settlement may have been significantly higher for those represented by attorneys. In other words, for claimants with similar injuries, the overall cost of claims with attorney-represented claimants may be significantly higher than the cost of claims without attorney representation, even as the attorney-represented claimants themselves receive less net compensation. The excess costs (costs above what nonrepresented claimants would expect to receive) are payments paid to medical providers and attorneys.25

____________________________

24Insurance Research Council, Countrywide Patterns in Auto Injury Insurance Claims, 2018 Edition (Malvern, Pa.: Insurance Research Council, 2018), p. 55.

25Insurance Research Council, Countrywide Patterns in Auto Injury Insurance Claims, 2012 Edition (Malvern, Pa.: Insurance Research Council, 2012).

Many state workers compensation systems have also experienced steady growth in the percentage of claimants represented by attorneys. Like auto no-fault systems, workers compensation is intended to operate without extensive attorney involvement, and while workers with claims are prevented from filing lawsuits by exclusive-remedy rules, attorney involvement in many states is common, creating an adversarial atmosphere with behavior and outcomes very similar to what would be expected in a court-based environment. The Workers Compensation Research Institute (WCRI) reported in a 2017 study that attorney representation for 18 states studied ranged from 13 to 52 percent from 2013 to 2016, and the median rate of attorney representation grew 4.8 percentage points from 2002 to 2016.26

Aggressive attorney advertising is occurring at a time when the public may be particularly angry, concerned about income inequality, harboring poor opinions of big business, and feeling entitled to compensation (and lots of it). As a result, many are more willing to take the opportunity to hire an attorney to represent them in initiating an insurance claim and/or filing a lawsuit. Additional factors in the social inflation picture have been third-party litigation funding and the erosion of judicial standards and rules that acted as guardrails for the civil justice system, keeping the system responsive, efficient, and affordable.

____________________________

26Rui Yang, Karen Rothkin, Roman Dolinschi, Worker Attorney Involvement: A New Measure, Workers Compensation Research Institute, May 2017, p 17.

Third-Party Litigation Funding

Both parties in a lawsuit, the plaintiff and the defendant, face strong incentives to settle the lawsuit. Defendants, which may be individuals, businesses, or insurance companies, want to minimize the risk-adjusted cost of the lawsuit. Plaintiffs, on the other hand, want to maximize the risk-adjusted value of what they ultimately receive in compensation or damages. For defendants, a key incentive may be the desire to eliminate a potential liability of unknown amount. For plaintiffs, a key incentive is to receive a settlement or jury award sooner rather than later. This basic arrangement, which governed personal injury litigation for decades, was fundamentally altered several years ago with the emergence of third-party litigation funding (TPLF).

TPLF involves an outside entity that provides funds to a plaintiff in exchange for a percentage of the amount ultimately received, whether a settlement or jury award.27 If the lawsuit is unsuccessful, the plaintiff is under no obligation to repay the funds provided. TPLF, where involved, significantly alters the incentives plaintiffs face to reach a settlement sooner rather than later by providing plaintiffs with funds prior to the settlement of their claim. Plaintiffs are thus willing and able to hold out longer and force defendants to agree to a higher settlement amount. The fact that a plaintiff in a lawsuit is benefiting from funding provided by an outside party is not discoverable information in most jurisdictions.28 Defendants and juries, in most jurisdictions, are not entitled to information about any contractual agreements between a plaintiff and a TPLF source, and courts have no role or authority in approving TPLF arrangements.

Although data documenting the growth and current magnitude of TPLF are unavailable, reports suggest that the trend is real and having a serious impact on claim settlement outcomes.29 Growing investments by major hedge funds and private equity firms in litigation financing was described in a 2018 New York Times article that described TPLF as a $10 billion industry.30 TPLF has also been directly linked to activity involving mass torts and class action lawsuits31and has even been linked to litigation related to the #MeToo movement.32

Litigation funding neutralizes the incentive plaintiffs have to settle claims and lawsuits in a timely manner. By adding uncertainty and lengthening the settlement timeline, TPLF increases the settlement value of a claim and the ultimate cost to defendants, who must agree to higher demands or risk having a jury decide the cost of a case. To the extent that the changes in underlying attitudes and opinions discussed earlier generate additional claims and lawsuits, litigation funding provides a clearer and easier path by which those claims and lawsuits can proceed and increases the ultimate cost of the claims and lawsuits involved.

Very Large “Nuclear” Verdicts

One manifestation of social inflation is the increasing number of very large verdicts, sometimes referred to as nuclear verdicts. A very large verdict may far exceed the plaintiff's actual economic losses and is likely to cause severe financial stress for the defendant. Nuclear verdicts might be any size but typically are greater than $10 million and in some cases many times higher. Very large verdicts are seen as having strong emotional and punitive elements. Where the defendant is a corporation or healthcare provider, effort is made to portray the defendant as a big business with deep pockets that deserves to be punished.33

Very large verdicts are becoming increasingly frequent. In 1999, less than 10 percent of all medical malpractice insurance claims cost more than $500,000. By 2017, almost 20 percent cost that much. And the countrywide number of malpractice verdicts greater than $25 million grew from 4 in 2014 to 17 in 2018.34 Very large verdicts are also discussed frequently in the context of commercial auto insurance. Average jury verdicts against trucking firms increased from $2.6 million in 2012 to $17 million in 2019.35 A broad review of jury verdicts across the U.S. found a 300% increase in the frequency of verdicts $20 million or more in 2019 from the annual average during the period 2001 through 2010.36

While many of the largest nuclear verdicts have been associated with commercial and professional liability claims, private passenger auto insurance is experiencing similar effects as jury sympathy toward plaintiffs has grown along with the willingness to punish at-fault drivers. Despite the role that policy limits play in constraining claim cost growth, very large jury verdicts still affect personal auto claim costs. As noted above, research from IRC documents growth in claim severity that far exceed economic inflation, and unpublished analysis by IRC indicates significant growth in the proportion of bodily injury liability claims being paid at policy limits.

Very large verdicts are a clear manifestation of social inflation as claimants and plaintiffs seek and expect higher insurance claim settlements and awards in personal injury lawsuits, and juries are eager to provide more generous compensation to plaintiffs and are more willing to punish those who cause injury to others. The cost of very large verdicts can be far greater than the sum of the verdicts themselves. Very large verdicts have a strong signaling effect on insurance claimants and insurers, resulting in higher settlement costs across a broad class of insurance claims. They also contribute to the underlying attitudes and opinions associated with social inflation by normalizing litigiousness and entitlement to compensation and thus encouraging even more claiming activity and litigation.

Class Action Lawsuit Abuse

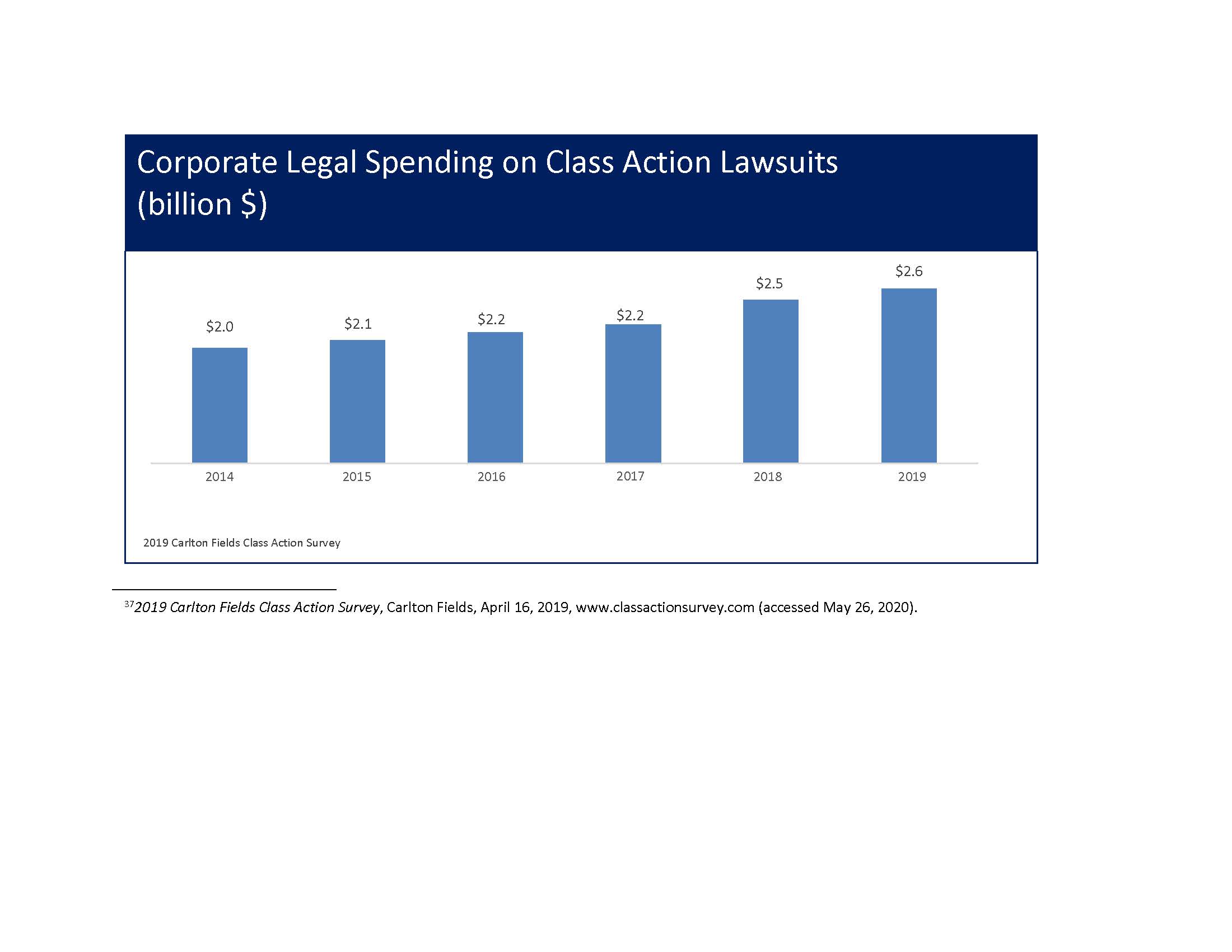

As discussed earlier, U.S. public confidence in big business has fallen to historic lows. Consistent with the low opinions many individuals have of corporate America, and facilitated by aggressive attorney advertising, a wave of class action lawsuits has swept across the corporate landscape. A class action lawsuit is one that includes multiple plaintiffs joining together in litigation seeking damages from a single defendant. There is no system currently in place to track the number, cost, and outcomes of class action lawsuits. However, the law firm Carlton Fields estimates that corporate spending dedicated to defending against class action lawsuits totaled $2.6 billion in 2019, an increase of 30 percent from $2.0 billion in 2014. In 2018, spending on class action lawsuits accounted for 11 percent of all corporate spending on litigation in the U.S., and approximately 54 percent of all companies reportedly faced one or more class action lawsuits.37

_____________________

27David H. Levitt and Francis H. Brown III, Third Party Litigation Funding, Civil Justice and the Need for Transparency, DRI Center for Law and Public Policy, Chicago, IL, 2018.

28Wisconsin and West Virginia have recently enacted laws requiring disclosure of TPLF arrangements, and the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California adopted rules requiring the disclosure of TPLF agreements in proposed class-action lawsuits.

29John Divine, “Litigation Finance: How Wall Street Invests in Justice,” U.S. News & World Report, Jan. 22, 2018, money.usnews.com/investing/stock-market-news/articles/2018-01-22/litigation-finance-how-wall-street-invests- in-justice (accessed May 26, 2020).

30Matthew Goldstein and Jessica Silver-Greenberg, Hedge Funds Look to Profit From Personal-Injury Suits, The New York Times, June 25, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/25/business/hedge-funds-mass-torts-litigation-finance.html (accessed May 26, 2020).

31"Selling More Lawsuits, Buying More Trouble,” Third-Party Litigation Funding A Decade Later, Institute for Legal Reform, U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Washington, DC, January 2020.

32Matthew Goldstein and Jessica Silver-Greenberg, How the Finance Industry is Trying to Cash In on #MeToo, The New York Times, January 28, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/28/business/metoo-finance-lawsuits- harassment.html (accessed May 26, 2020).

33Emily Spennato, Nuclear Verdicts Have the Board on Edge? Jury Consulting Can Help Level the Legal Playing Field, Risk & Insurance, riskandinsurance.com, Sept. 13, 2019 (accessed May 4, 2020).

34Richard E. Anderson, Behind the Rise in Large Outlier Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Physicians Practice, February 21, 2020, https://www.physicianspractice.com/article/behind-rise-large-outlier-medical-malpractice-verdicts (accessed May 26, 2020).

35Kim Palmer, A Few Industries Drive Commercial Insurance Rates Higher for Everyone, Crains Cleveland Business, January 26, 2020, https://www.crainscleveland.com/government/few-industries-drive-commercial-insurance-rates-higher-everyone (accessed May 26, 2020).

36Telis Demos, The Specter of Social Inflation Haunts Insurers, Wall Street Journal, December 27, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-specter-of-social-inflation-haunts-insurers-11577442780 (accessed May 4, 2020).

372019 Carlton Fields Class Action Survey, Carlton Fields, April 16, 2019, www.classactionsurvey.com (accessed May 26, 2020).

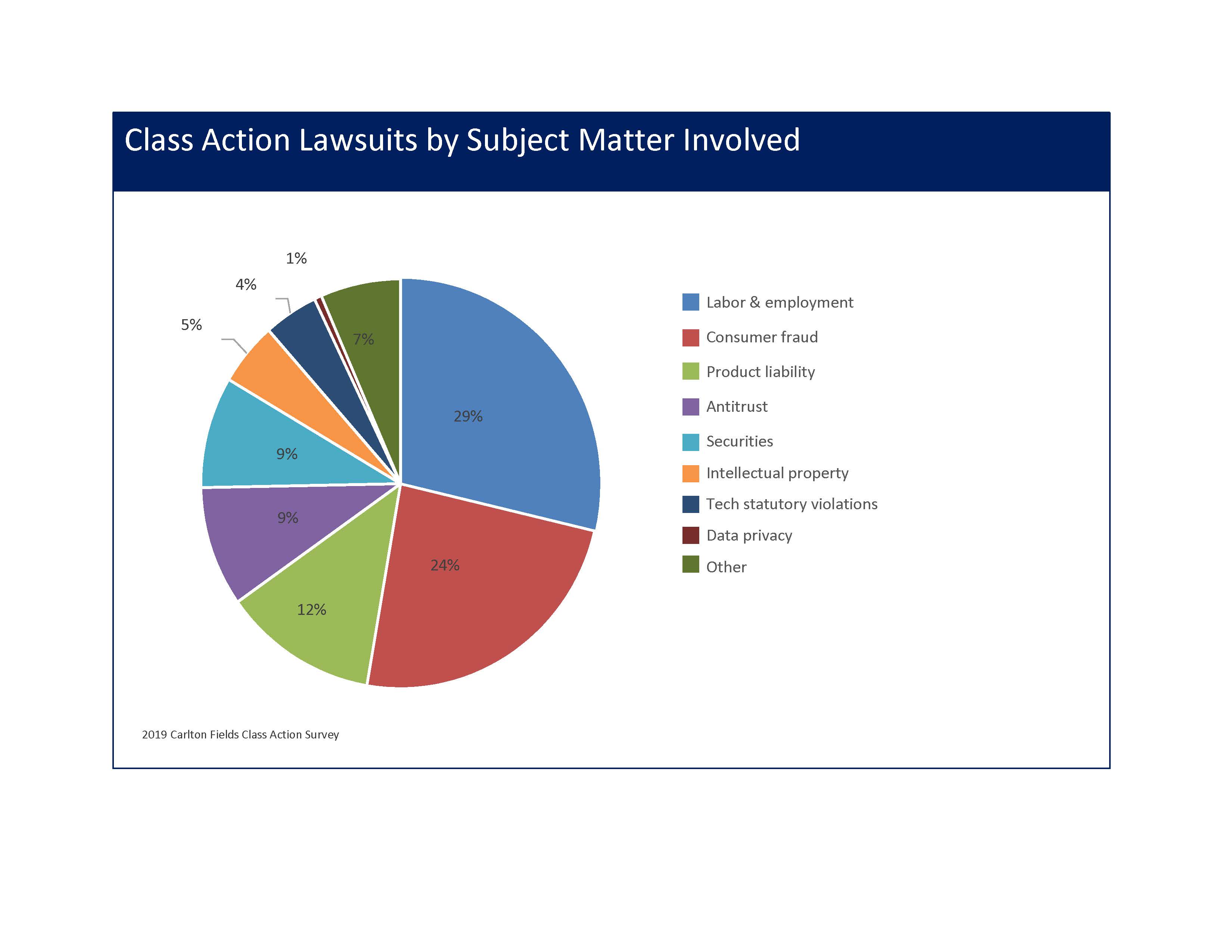

Class action lawsuits may involve a range of issues. Based on a 2019 survey of corporate legal staff, the most common subjects of class action lawsuits in 2019 were labor and employment matters (29 percent), followed by allegations of consumer fraud (24 percent).38

Although comprehensive data measuring class action litigation are not available, data are available for one particular type of class action—those involving securities. According to the Institute for Legal Reform (ILR), the number of securities class action lawsuits filed increased from 121 in 2012 to 412 in 2017.39Securities-related class action lawsuits, particularly those involving mergers and acquisitions, have attracted considerable interest from shareholders and their attorneys because the settlement value of the lawsuit may be directly tied to the market capitalization of the firms involved. According to ILR, virtually all proposed mergers and acquisitions involving public companies now trigger lawsuits alleging false and deceptive disclosures to shareholders. In some instances, individuals purchase small numbers of shares in numerous public companies viewed as likely to be involved in future mergers or acquisitions with the sole intent of filing securities class action lawsuits when a merger or acquisition is subsequently proposed. This scenario whereby willing and eager litigants are targeting corporate deep pockets, aided by eager trial attorneys, is one of the clearest and most recent manifestations of social inflation in recent years.

_____________________________________________

38Ibid.

39A Rising Threat, Institute for Legal Reform, Oct. 24, 2018, https://www.instituteforlegalreform.com/uploads/sites/1/A_Rising_Threat_Research_Paper-web_1.pdf (accessed May 26, 2020).

Potential Future Social Inflation—Restatement of the Law, Liability Insurance

In addition to the factors and conditions contributing to social inflation in recent years, another development presents a potential additional source of social inflation. In 2010, the American Law Institute began a comprehensive effort to prepare a survey of common law on legal topics related to liability insurance known as the Restatement of the Law, Liability Insurance. The purpose of a Restatement is to provide judges, lawyers, and others with guidance on current legal precedent and predominant interpretations of common law. 40The Restatement of the Law, Liability Insurance, which was approved in 2018, has attracted considerable criticism from the insurance industry and state legislatures based on assessments that it proposes significant changes in current principles and rules that could, if applied, significantly expand insurer liability. Two state legislatures, Kentucky and Indiana, passed resolutions in 2019 opposing the Restatement, and several others have taken steps to inhibit its use based on perceived conflicts with existing state laws and the undermining of the states' authority to regulate insurance.41While the ultimate impact of the Restatement is not known at this time, there is widespread opinion that the adoption of many of its provisions could significantly increase liability costs in a number of coverage areas.42

Conclusion

Social inflation is having a direct and significant impact on liability insurance results, generating rapid increases in insurance claim losses. Although primarily affecting commercial insurance products, social inflation is also leading to higher personal auto liability claim costs. Social inflation is a multifaceted issue, with roots in the public's changing views and opinions about the appropriateness of filing lawsuits and changing expectations regarding the amount of compensation to be received. Attorney advertising, third-party litigation financing, class action lawsuits, tort reform rollbacks, and nuclear verdicts play important roles in prompting and facilitating potential claimants and litigants to file insurance claims and initiate litigation, and measures targeting these issues may help stem the cost growth associated with social inflation.

Insurance Research Council

June 2020